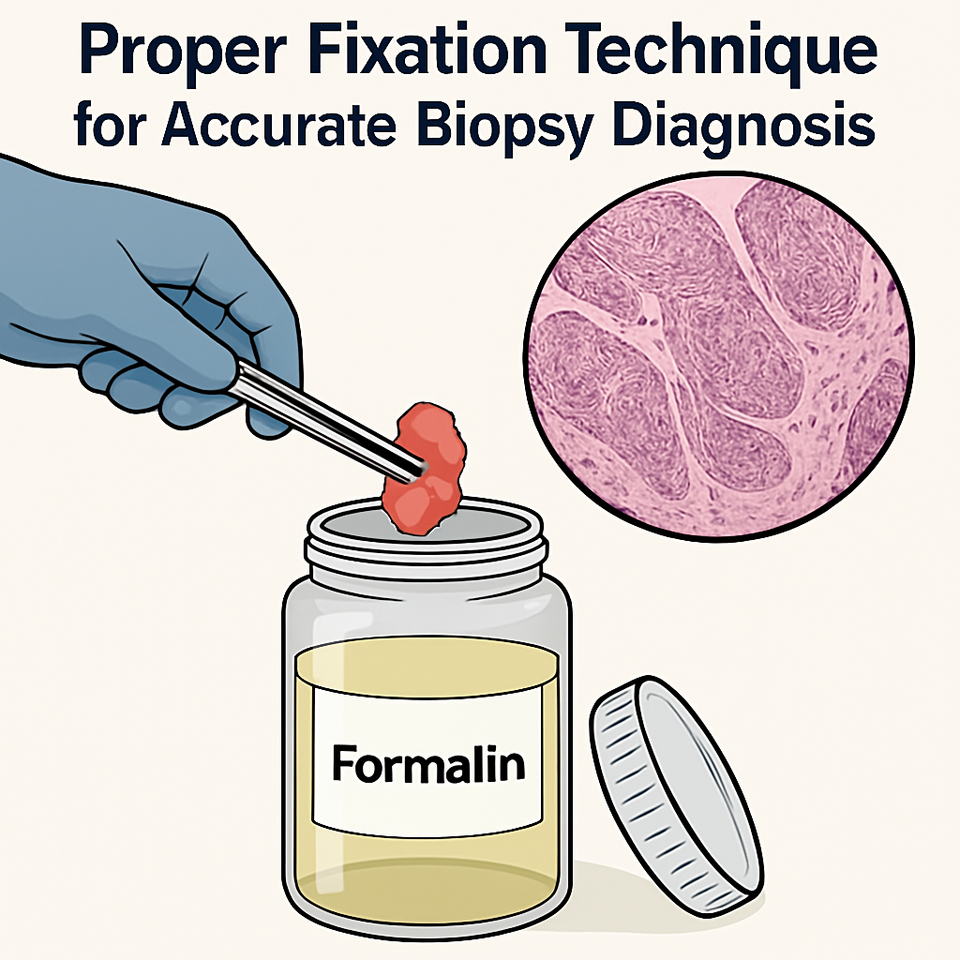

Proper Fixation Technique for Accurate Biopsy Diagnosis

Published in General & Internal Medicine

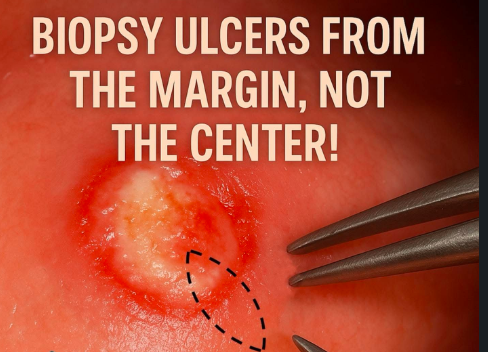

Biopsy is not merely the act of removing tissue; it is a deliberate, technique-driven diagnostic intervention that can define the entire trajectory of patient care. One of the most critical principles is to biopsy from the active edge of an ulcer or lesion, never from the necrotic centre. The central zone of chronic ulcers often contains degraded, non-viable tissue filled with inflammatory cells and necrotic debris, which provides little diagnostic value. Instead, always sample from the interface between normal and abnormal tissue, where the pathological process begins and diagnostic features are preserved.

Depth and completeness of the biopsy are crucial. A superficial shave or small surface scraping may completely miss the deeper pathology, especially in neoplastic, dysplastic, or infiltrative lesions. The ideal biopsy should include epithelium, connective tissue, and when appropriate, underlying muscle, salivary gland, or bone. A partial sample may result in false negatives, delaying definitive management.

Instrumentation must be precise. Always use a sharp #15 blade for incisional biopsies or a sterile, properly sized punch biopsy tool (typically 3–5 mm diameter). Dull blades or excessive force with forceps can introduce crush artefact, tearing epithelial-connective junctions and compromising architectural integrity. When handling tissue, use toothed Adson forceps only to grasp the periphery, never the centre, to avoid distorting diagnostic zones.

Electrocautery should be avoided during the initial excision because it produces thermal artefacts that can obscure dysplastic changes or mimic cellular atypia. If hemostasis is required post-biopsy, gentle application at a safe distance from the biopsy edge is recommended. Cold steel technique remains the gold standard for primary sampling.

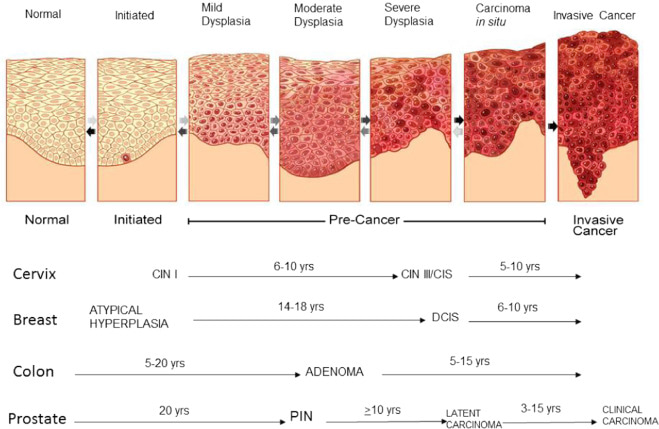

Orientation and inking matter in cases where margins are critical, particularly in suspected carcinoma or premalignant lesions such as epithelial dysplasia. These lesions often show histological hallmarks like loss of polarity, nuclear hyperchromasia, increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, basal cell hyperplasia, and disordered maturation, all of which may be patchy or focal. Hence, precise orientation is vital for assessing whether dysplastic or neoplastic changes reach the surgical margins. As illustrated in epithelial carcinogenesis, lesions progress through well-defined stages from normal epithelium to mild, moderate, and severe dysplasia, then carcinoma in situ, and eventually invasive carcinoma. This multistep transformation may span years to decades, depending on tissue type, ranging from 5–10 years in cervical CIN progression to over 20 years in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) evolving into carcinoma. Identifying and fully excising these precursor stages is essential to halting progression. To aid accurate pathological margin assessment, always secure the biopsy’s orientation with a suture at one end or mark specific borders using surgical ink (e.g., medial, lateral, or deep margin). This spatial information should be documented on both the histopathology request form and specimen container, ensuring optimal communication with the pathologist for margin status interpretation and further surgical planning.

Always submit separate lesions in separate, clearly labelled containers. Do not combine tissue from different anatomical sites or lesions unless they are contiguous and part of a single pathological process. Mislabeling or pooling can render the histopathology report non-conclusive or misleading.

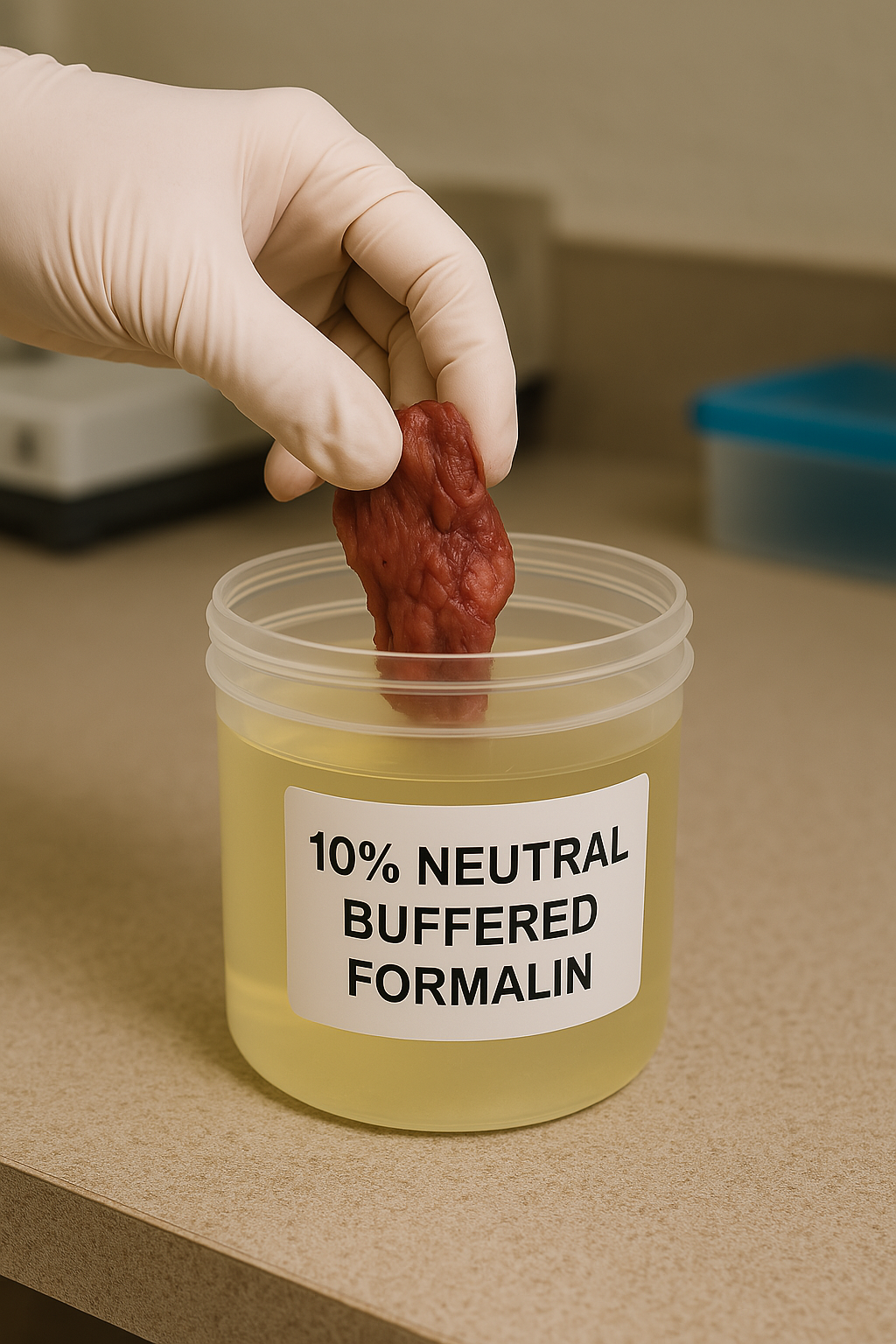

Fixation begins immediately. Immerse tissue in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) in a container large enough to hold at least 10 times the tissue volume. Delayed fixation, particularly in warm climates, leads to autolysis and degradation of key histologic features, especially nuclear detail.

In cases of suspected infectious pathology, such as tuberculosis, deep fungal infections, or viral ulcers, consider taking a second sample for microbiological analysis. Fresh tissue may be sent in saline or appropriate transport media for PCR, fungal culture, or AFB testing, as formalin-fixed specimens are not suitable for culture or some molecular assays.

Documentation is part of the technique. Always provide comprehensive clinical details on the requisition form: lesion site, duration, size, suspected diagnosis, relevant history (e.g., tobacco use, immunosuppression, systemic disease), and any medications. This context enables the pathologist to interpret histologic findings with precision and, when needed, apply targeted IHC or molecular stains.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in