Public Perceptions and Support of Climate Intervention Technologies across the Global North and Global South

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Civil Engineering

We currently bear witness to the increasing devastations of climate change, a sobering testament to the insufficient progress humanity has made in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The horizon of potential solutions is widening, including the consideration of novel, potentially radical climate-intervention technologies. These include carbon dioxide removal (CDR) approaches, more familiar ecosystem-based forms of afforestation and soil carbon sequestration as well as novel engineered approaches such as direct air capture, and solar radiation modification (SRM) methods such as stratospheric aerosol injection and space-based geoengineering. While more scientists and policymakers are wading into these debates, the public remains substantially unfamiliar with climate-intervention technologies and what they entail. This limits the ability of publics to engage and participate in important discussions around their potential research and use. Just as crucially, the lack of understanding of public perceptions at a global level opens up the risk of actors speaking on behalf of publics, particularly in the Global South, in ways that reduce or do not reflect their actual perspectives and concerns.

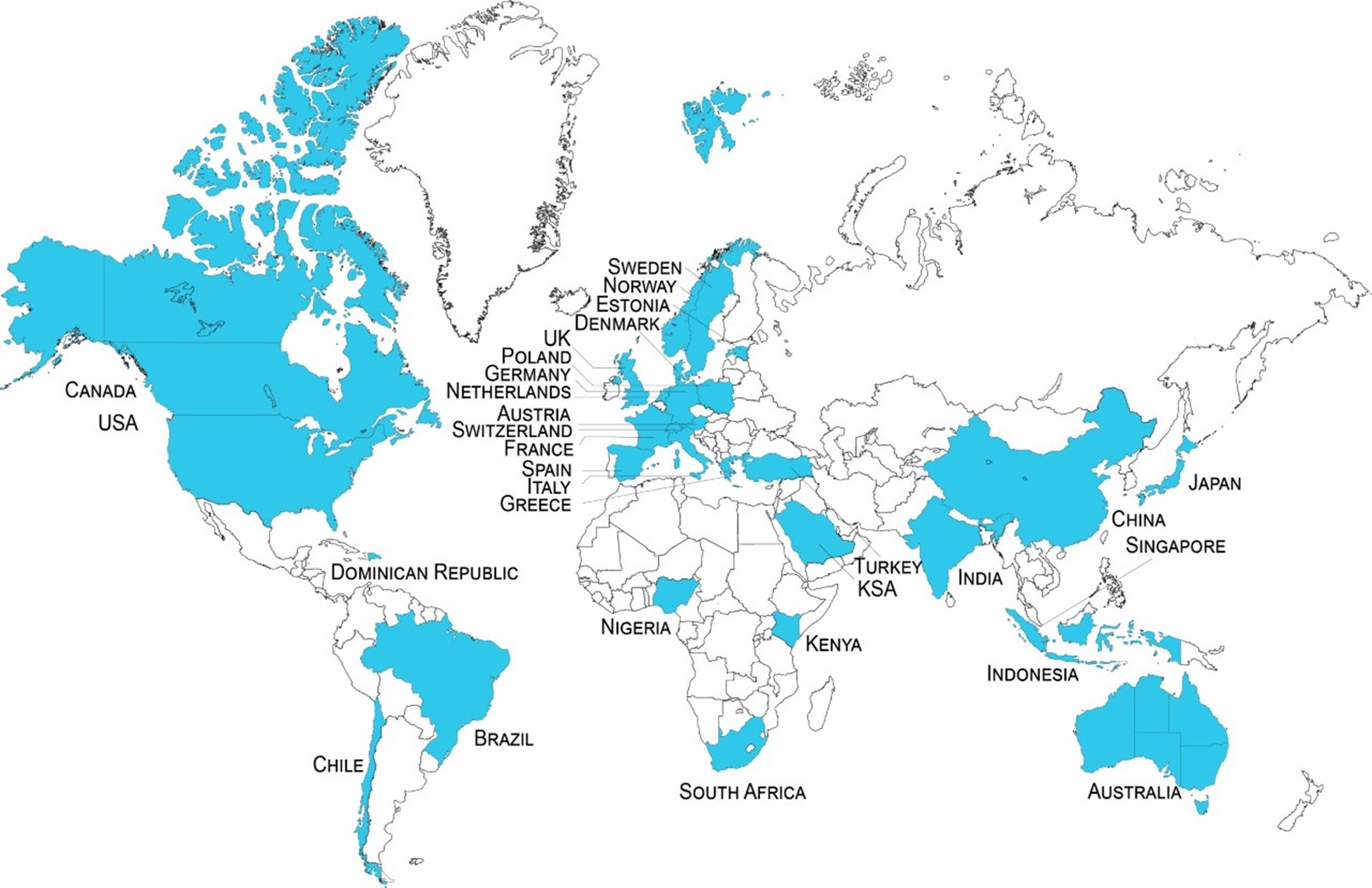

In this paper, we draw on a large-scale, cross-country exercise of nationally representative surveys (N=30,284) in 30 countries and 19 languages to establish- the first global baseline of public perceptions of climate-intervention technologies. The survey instrument examined ten climate-intervention technologies that have been the focus of most research and discussion, with participants randomly assigned to read about one of the three following technology categories: Solar Radiation Modification (stratospheric aerosol injection, space-based geoengineering, marine cloud brightening); ecosystem-based Carbon Dioxide Removal (afforestation and reforestation, soil carbon sequestration, marine biomass and blue carbon); and engineered Carbon Dioxide Removal (direct air capture with carbon storage (DACCS), bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), enhanced weathering, biochar). Our definition of Global South follows the classification of the United Nations' Finance Center for South-South Cooperation, officially used by the UN for distributing development funding.

Our main finding was that publics across the Global South were significantly more supportive of all technologies - with the exception of afforestation and reforestation. We also find that the most-supported technologies tended to be the ecosystems-based CDR approaches, followed by the engineered CDR approaches and, lastly, the SRM approaches.

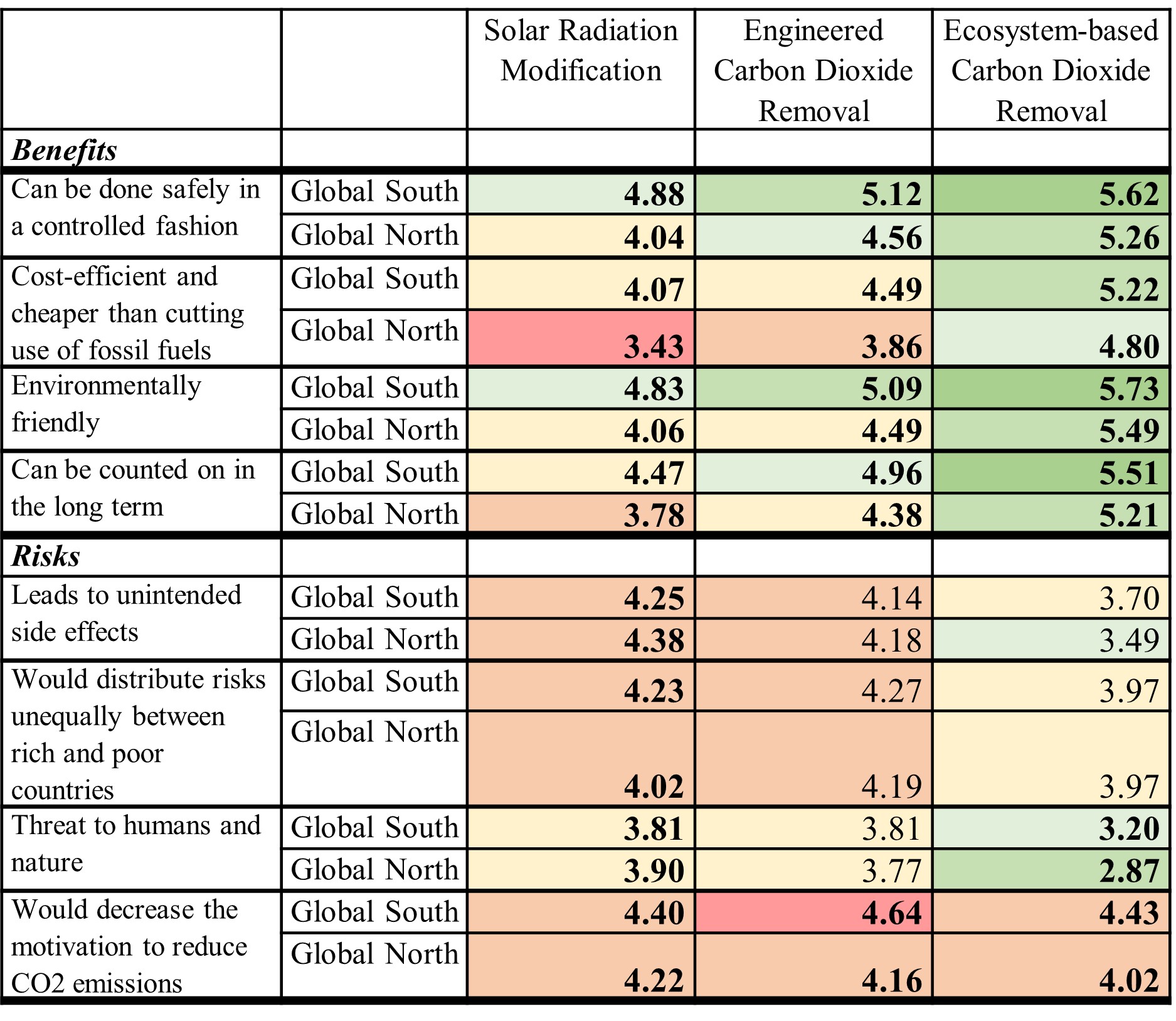

Similarly, we established that participants in the Global South were consistently more positive about the potential benefits of climate-intervention technologies, no matter the technology category. Mirroring the results for support, publics were more positive about the benefits of ecosystems-based CDR approaches. However, the divergence between publics in the Global South and Global North was sharpest for the SRM approaches.

Differences between the cohorts are more nuanced when it comes to potential risks. Most of the disagreement centered on SRM, with greater concern expressed in the Global North regarding unintended side effects and the threat to humans and nature. Conversely, Global South publics focused on unequal distributions of risks between rich and poor countries and whether the use of SRM would undercut climate-mitigation efforts. The possibly fraught relationship between emissions reductions and climate-intervention technologies was indeed of general and deeper concern in the Global South.

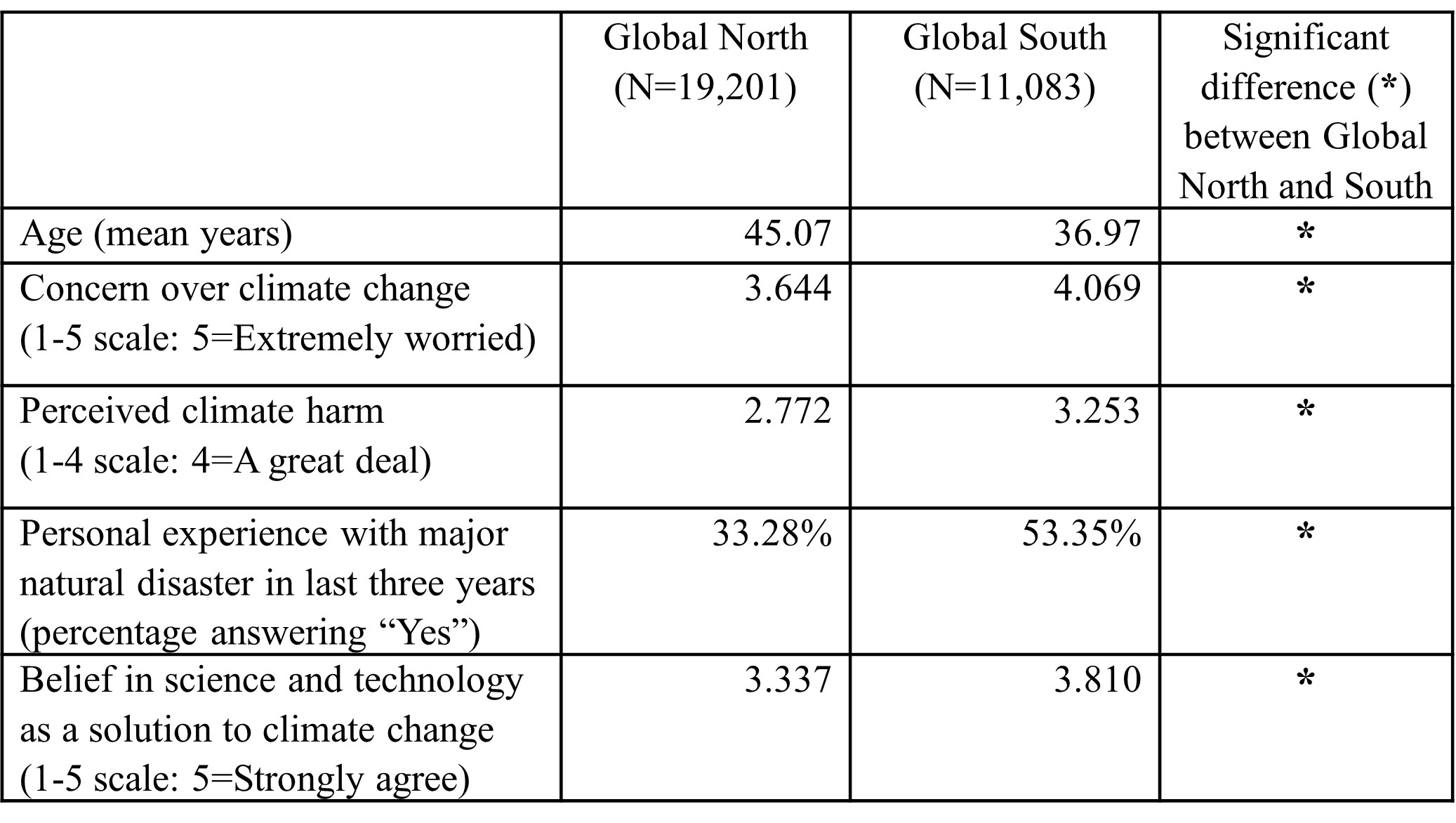

Rather than leaving these as unexplained cohort differences, we examined how the publics we surveyed in the Global North and Global South differed in some key respects. We identified many significant differences, with those in the Global South younger overall. They were also more concerned about climate change and more likely to expect greater personal harm and to have experienced a major natural disaster (e.g., flood, heatwave, wildfire, blizzard) in the last three years. In total, these factors suggest a more refined account of how and why Global South and Global North significantly differ in their support for climate-intervention technologies.

Ultimately, our results illustrate a desire, particularly among those in the Global South, to engage with climate-intervention technologies in a proactive way – though this by no means indicates that publics are blind to the risks that such options might pose. This also demonstrates that the perspectives and preferences of experts do not clearly reflect those of the publics, most notably those across the Global South. The takeaway is clear: there is no substitute for directly engaging with publics in the Global South.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in