Enjoy the full story in our Nature Communications paper: "Multi-layered ecological interactions determine growth of clinical antibiotic-resistant strains within human microbiomes".

At the end of 2020, during the COVID pandemic, I started a new chapter by moving to ETH Zurich (Switzerland). It was not only a geographical change, but also an extension of the perspective I had been developing. I was coming from a more clinical view of antimicrobial resistance, studying the dissemination and evolution of resistance plasmids in the human gut and hospitals. This brought me into a much more ecological setting, joining the Pathogen Ecology group.

I was wondering whether we could understand more about what actually determines invasion success when resistant bacteria enter complex microbial communities. What are the ecological implications? What drives the strain turnover in the human gut? Why do some resistant strains establish themselves in a microbiome, and others do not?

“Resurrection”

With the initial aim of focusing on plasmids and horizontal gene transfer within communities, we instead zoomed out and planned to answer a broader question. What factors influence whether different strains of the same species succeed or fail when introduced into a microbial community?

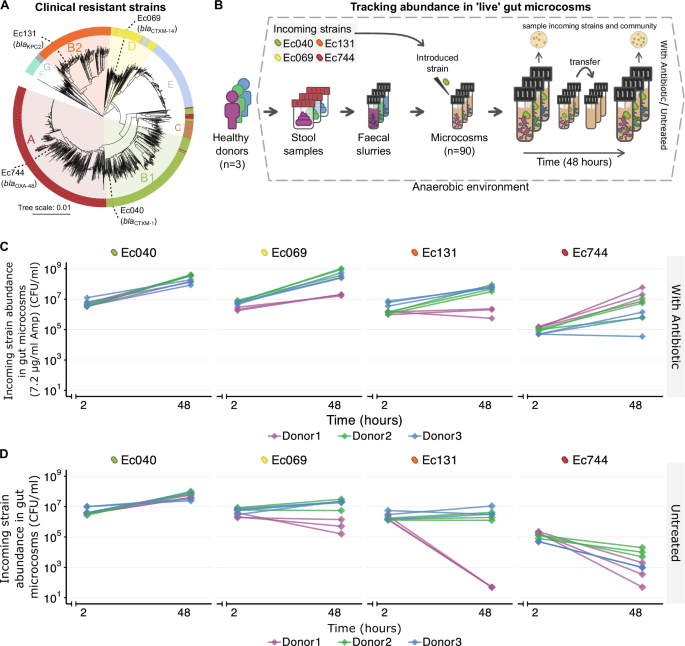

Tracking strain fate in 'live' gut microcosms. Left: anaerobic preparation of gut microcosms. Right: schematic of the replicated invasion assay across microbiomes, with and without antibiotics (90 microcosms).

While waiting for the Coy anaerobic chamber to arrive, I planned the experimental design, the ‘live’ microcosm assay. We selected a group of E. coli strains isolated from hospital patients. They were all phylogenetically distinct, belonged to different phylogroups, and carried different clinically relevant plasmids (encoding Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases –ESBLs– and carbapenemases). Then we collected stool samples from healthy volunteers to prepare the replicated anaerobic gut microcosms. This system allows us to observe interactions between strains, species, and whole communities under controlled conditions, while still keeping a relevant part of the ecological complexity that matters in vivo.

"Betrayed"

We hypothesised that different strains within the same species would exhibit different interactions with resident microbiota, leading to variable invasion outcomes. With antibiotics present, the system looks simple. Resistant strains grow. Competition is lower, and the advantage brought by the resistance genes behaves as expected. Once antibiotics are not included, some strains continue to grow successfully, while others never grow at all.

More strikingly, these differences already appear under the specific abiotic conditions (sterilized microcosms), without any resident community. Despite being isolated from the gut of patients, we observed substantial variability in their growth capacity in the absence of antibiotics. This strain-specific intrinsic growth capacity already sets a threshold before the competition begins.

Intrinsic growth capacity. Clinical E. coli strains differed in their ability to grow under gut-relevant abiotic conditions. These strain-specific differences already constrained invasion outcomes.

"Beloved"

Once the community is taken into account, the fate of the incoming strain is no longer purely individual. Interspecies interactions come into play. Some strains not only grow better than others, but also reshape the microbiome around them. They shift abundances, displace taxa, and alter local equilibria. Others grow almost unnoticed.

Success depends not only on tolerating the community, but also on how the community responds to the presence of the newly arrived strain. And that response depends not just on who arrives, but also on the microbial composition of the community that is already there. Some communities are more permissive, others are more resistant to change.

Being “accepted” or successful does not mean being invisible to the community. It means finding a way to coexist, or compete, without triggering exclusion.

Interspecies interactions reshape strain performance. Once introduced into 'live' gut microcosms, incoming strains interacted differently with resident microbiota. These interspecies interactions varied across microbiomes, amplifying or limiting growth in a community-dependent manner.

"Harvest"

In the end, this converges on one question: what remains after competition?

One difference when using human stool samples is that, as in most human gut communities, E. coli is already present. Intraspecies interaction can make competition harder. Broad metabolic capacity does not guarantee success. What we harvest from the system is what a strain actually achieves when space is limited and a metabolic niche is occupied. Some strains manage to establish themselves after outcompeting the resident E. coli strains; others lose ground being outcompeted, even after initially successful growth.

Competition within species further drive success. In the microcosms E. coli was already present, direct competition with these resident strains strongly influenced success.

Under these conditions, even plasmids, the carriers of resistance, leave only a faint trace if the host strain does not prosper. Horizontal transfer occurs, but it rarely changes the immediate outcome in these conditions.

The final balance is driven by the combination of the strain-specific intrinsic growth, intra- and interspecies competition, and community structure across microbiomes. The invasion does not end with a clear success. It ends with an asymmetric distribution of opportunities, set not only by the invader, but by the community it enters and the surrounding environment.

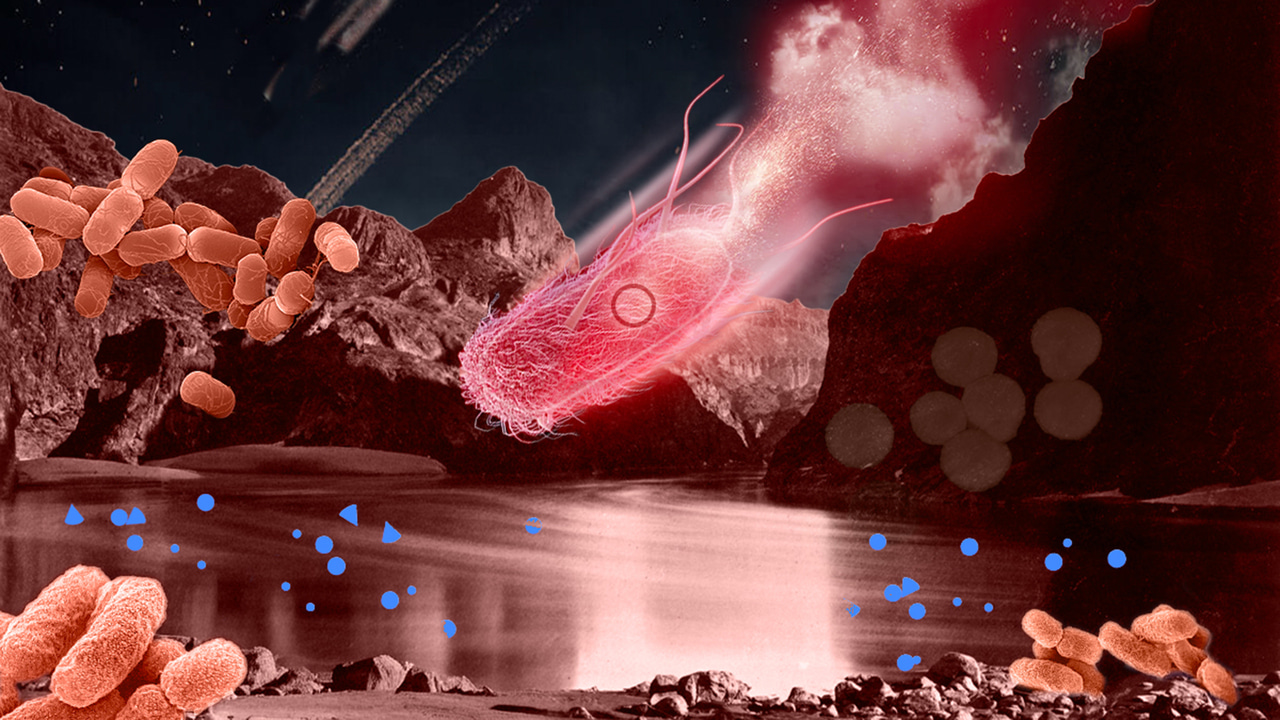

Visualising strain invasion across ecological layers in the gut microbiome. This illustration captures the multi-layered interactions shaping strain establishment within complex microbial communities. Both this image and the cover artwork were designed for this project by @Helena Klein (illuzation), Visual Science Communicator.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in