Shock-proofing conservation: are community forests in Madagascar resilient to a political crisis and its aftermath?

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Ecology & Evolution

Community-managed conservation areas can be an effective strategy for conserving biodiversity while still allowing local people to benefit from the sustainable use of natural resources. However, in many parts of the world, economic and political shocks challenge the ability of communities to protect biodiversity while also meeting their basic needs.

In Madagascar, threats to both people and biodiversity are severe, due to high rates of poverty and food insecurity, coupled with unsustainable rates of deforestation. Since its independence in 1960, the island country has suffered from repetitive political crises, but the one from 2009 to 2014 was the most severe and prolonged in the nation’s history, exacerbating both humanitarian and environmental issues. Given that much of the world’s biodiversity is concentrated in politically fragile nations like Madagascar, understanding whether community managed conservation areas are as resilient as state-managed protected areas to a crisis is essential if we want to avoid species extinctions and the loss of ecosystem services.

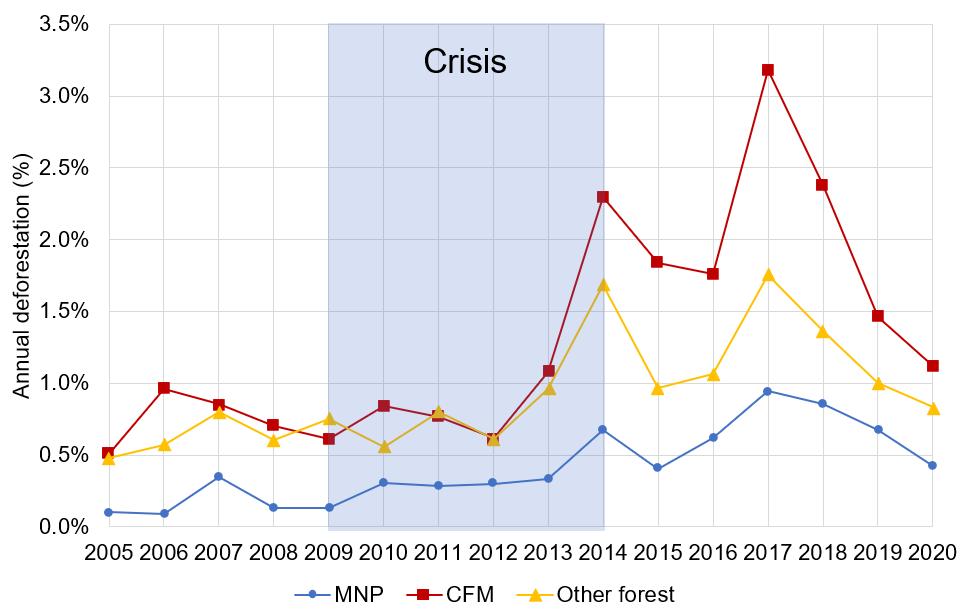

In our recent paper, we explored the impacts of the Madagascar political crisis, and its immediate aftermath, on the performance of community managed forests. We compared deforestation rates in Community Forest Management (CFM) and protected areas administered by Madagascar National Parks (MNP), as well as all forests nationally, before, during, and after the political crisis. In Madagascar, CFM were established starting in the late 1990s with the objective of preventing forest loss, while also providing a sustainable flow of forest products to benefit local communities. MNP protected areas are much older and were established to protect forests and biodiversity, not to provide livelihoods for local populations, except from tourism in some protected forests. Unfortunately, MNP, CFM, and forested areas all experienced deforestation before, during, and after the political crisis (Figure 1). Rates of deforestation were higher in CFM than MNP in all three time periods.

Unlike previous research showing spikes in illegal logging (especially of rosewood and other precious hardwoods) during the crisis, we found that deforestation rose significantly only in the last year of the crisis and for several subsequent years (2014-2017) before returning to (or slightly above) pre-crisis levels. To our knowledge, this post-crisis deforestation spike has not been previously reported and, to date, cannot easily be explained by us or other experts working in the region. In the paper we propose several theories, and we hope that future research will explain this worrisome phenomenon and explore whether other conservation hotspots suffering political crises experience similar patterns.

Figure 1. Annual deforestation (as a percentage of 2000 forest cover) 2005-2020 in Community Forest Management areas (CFM, red squares), protected areas administered by Madagascar National Parks (MNP, blue circles), and the rest of the country (other forest, yellow triangles). Values greater than zero indicate forest loss in a given year. Deforestation percentages are based on baseline forest cover in 2000, the earliest year for which there is consistent annual data. The crisis period (2009-2014) is shown in light blue shading.

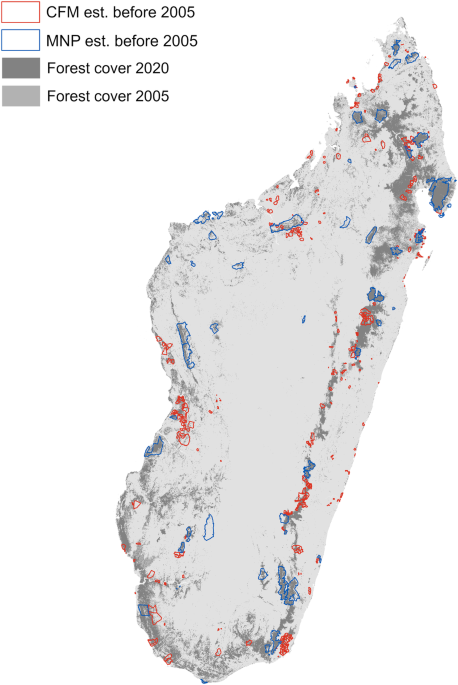

Our research also underscores the careful analysis required to investigate these kinds of questions. In our case, CFM differ systematically from MNP in ways that are expected to increase pressure; they are smaller, more fragmented, and are located closer to roads and human population centers (Figure 2). If not controlled for, these confounding factors would bias estimates of deforestation outcomes in CFM and MNP, making it difficult to tease out the effects of the political crisis. To address this, we used quasi-experimental methods: statistical matching to control for differences in location and other time-invariant characteristics, and an event study estimator to control for differences in time-variant variables such as climate and commodity prices. This enables us to make a more robust ‘apples to apples’ comparison, as well as study the effects of the crisis over time.

Figure 2. Ranomafana National Park (top) and landscape surrounding Anjozorobe community forest (bottom). Differences in location result in very different levels of deforestation pressures in community forests compared to protected areas, making it challenging to compare performance. Photo credits: Trond Larsen, Rachel Neugarten

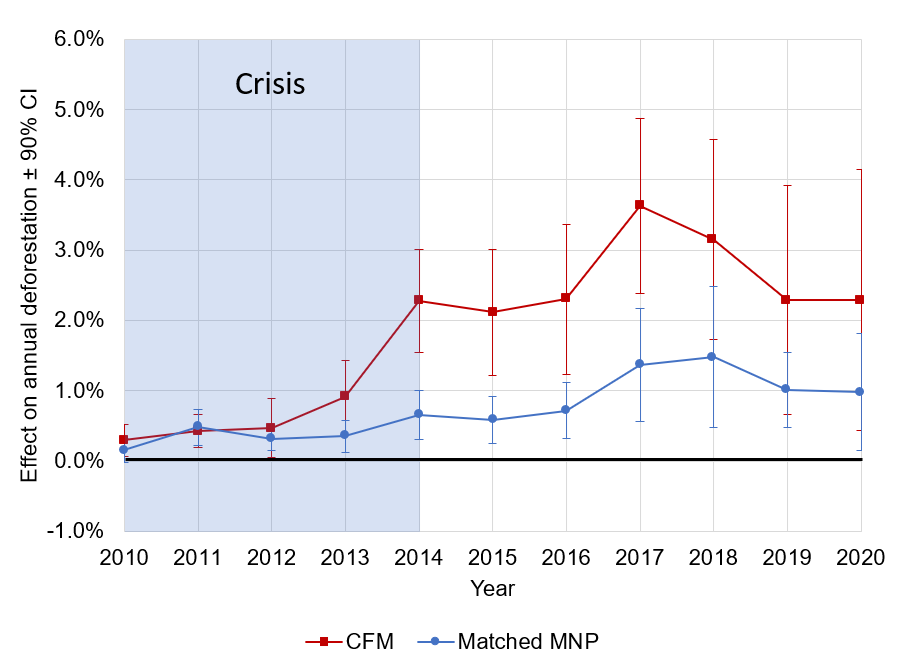

After controlling for confounding factors, we found that CFM and matched areas within MNP both performed poorly during the crisis years, but that their performance was not statistically significantly different from one another until the end of the crisis (Figure 3). In other words, CFM and MNP were equally vulnerable to the effects of the crisis. In the post-crisis period, when deforestation rates spiked nationally, CFM performed significantly worse than matched areas within MNP. This indicates that when deforestation pressures intensified as the economy began recovering from the crisis, community management withstood forest loss pressures less well than MNP did. This is a discouraging finding, as there was hope that community-managed conservation would effectively protect forests in Madagascar.

Figure 3. Event study results. Effects of the political crisis on performance of Community Forest Management areas (CFM, red squares) and protected areas administered by Madagascar National Parks (MNP, blue circles) in terms of annual deforestation, after matching and controlling for time-variant covariates. Estimates greater than zero indicate more deforestation (poor performance). Y-axis values represent the estimated effect size of the political crisis on annual deforestation (mean percent tree cover loss per year) from an ordinary least squares regression using an event study design with fixed effects for forest grid cells. Error bars indicate 90% two-sided confidence intervals. Our sample consists of 11,626 observations within CFM and 4,244 unique observations within MNP (matched observations). The difference between the red and the blue points each year indicate differential effects of the crisis on CFM relative to matched MNP areas. The event study analysis controls for trends in the pre-crisis period (2005-2009), so the first data point represents the first crisis year (2010).

In summary, we found that the crisis and post-crisis dynamics negatively impacted Madagascar’s forests under both CFM and MNP designation. Community managed areas were especially vulnerable to the post-crisis spike in deforestation pressure, likely in part due to insufficient and inconsistent financial support. Given extremely high rates of poverty and food insecurity, it is understandable that such areas face especially intense pressures, as there is no financial incentive for protecting them. Clearing forests for agriculture and charcoal production was likely a way communities met their basic needs, but at the cost of biodiversity. Similarly, intensifying economic pressures can make it difficult for local people to restrict or prevent logging for the lucrative timber trade by external actors. The implication of these findings for conservation is that in under-resourced nations like Madagascar, community forests will need much more external support from government, international NGOs, or multilateral banks to avoid further forest clearing and associated biodiversity loss.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in