Studying the electric double layer structure: A small step for platinum, a big leap for electrochemistry

Published in Chemistry

When we picture a metal surface, we often imagine something smooth and flat. Metal electrodes, however, especially those used in catalysis, are anything but. At the atomic scale, they are composed of any combination of steps and defects. In our recent study, A comprehensive model for the electric double layer of stepped platinum electrodes, we explored how these surface features differ in their respective surface chemistries, and the marked effect of these differences on the electrochemical signal we measure.

The importance of the electrode-electrolyte interface

Electrochemical reactions happen at the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte. At this interface, ions rearrange themselves in response to a change in the electrode potential, forming the so-called electric double layer. Although only a few nanometers thick, this interfacial region dictates how charge is stored and plays a central role in determining electrode performance.

Since the mid-19th century, models of the electric double layer structure typically assume the electrode surface is perfectly flat. While useful, these models have rarely been extended to realistic, non-atomically flat electrodes, which can lead to discrepancies between theory and experiments.

Why platinum is a model system in electrochemistry

Platinum is one of the most important materials in electrochemistry, with widespread applications in fuel cells, sensors, and catalysis, particularly for hydrogen evolution. Despite being extensively studied at both a fundamental and applied level, however, the electrochemical response of platinum surfaces remains complicated.

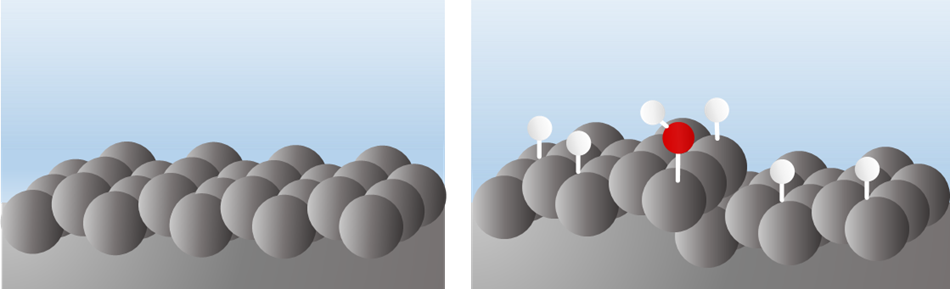

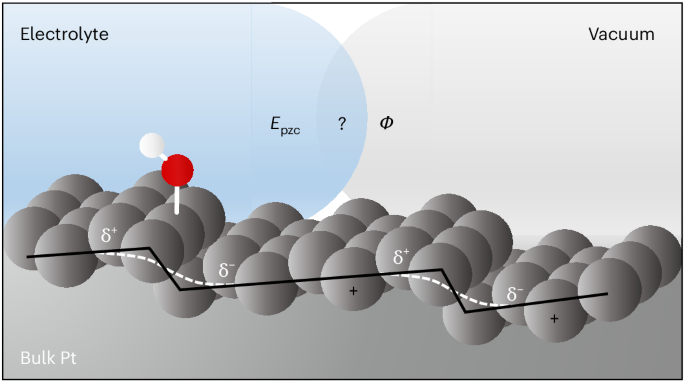

Only one type of platinum single-crystal surface: the Pt(111) surface, has a potential window in which interfacial water remains undissociated, often referred to as the double-layer region (left image). For all other platinum facets, however, H or OH adsorbates from water (H2O), or both, are present at the surface at any given potential (right image). This makes it difficult to distinguish whether a measured signal originates from stored electrical charge or from (electro)chemical reactions happening at the surface.

To determine the effect of defect sites on the structure of the electrical double layer, we systematically introduced two types of so-called step sites (110 and 100 type) to a flat 111 terrace. This approach allowed us to ask and ultimately answer a central question: How do these steps/defects and their respective catalytic activities change the structure and properties of electric double layer?

A simple measurement with an unexpected result

One key quantity we measured to answer this question is the differential capacitance, which describes how much charge the surface can store (and directly relates to the structure of the electric double layer). Under special conditions, i.e., very clean surfaces and extremely dilute solutions, the capacitance reaches a minimum at a particular electrode potential, known as the potential of zero charge. This potential is important because it is the potential at which the surface itself carries no excess charge, and is an important reference point, a kind of “sea level” for potential.

Unexpectedly, we found that the capacitance value of this capacitance minimum strongly depended on surface structure. When we added one type of step, the capacitance became smaller. When we added a different type of step, it became larger. Even more surprisingly, the potential at which the capacitance minimum occurred showed only a weak dependence on surface structure. This contrasts markedly with ultra-high vacuum measurements of the work function for the same platinum electrodes deviating from a classic theory by Alexandr Frumkin and Sergio Trasatti, which predicts a one-to-one correspondence between the potential of zero charge and work function.

We propose that these effects arise from differences in how water behaves at different step edges as a function of electrode potential.

When water behaves differently at different steps

At certain step types, water molecules dissociate and form adsorbates whose coverage remains essentially independent of potential. Other step types, however, cause water dissociated species to continually adsorb/desorb in a way that does change with electrode potential. This continual adsorption/desorption adds an extra contribution to the capacitance, even though it is a chemical effect (rather than due to changes in only the electric double layer structure).

In other words, not all platinum step sites are equal. Although they may appear similar structurally, they interact with water in fundamentally different ways and this has important implications for the capacitance we measure.

Simulations that explain what experiments cannot

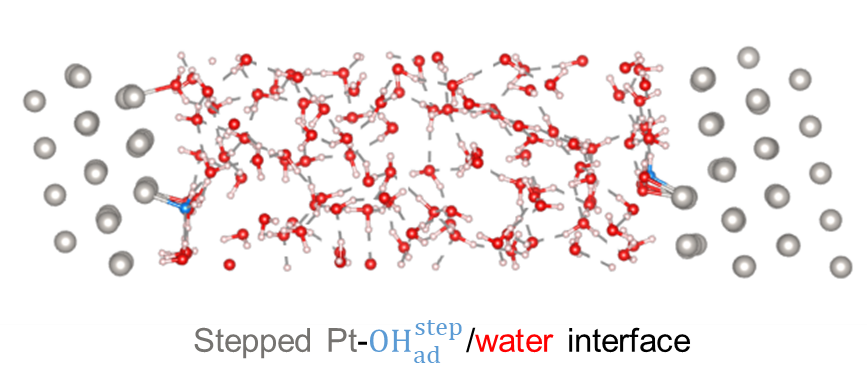

To understand this behavior more deeply, we combined our experiments with ab-initio molecular dynamics simulation that show, using first-principles quantum-chemical calculations, how electrons, metal atoms, and water molecules interact at the interface.

These simulations (see snapshot below) revealed that the water dissociated species adsorbed at step edges modify how the surface interacts with the solvent environment in a way that also causes a marked shift in the potential at which the surface appears electrically neutral. This helped us explain why our experimental results differed from earlier measurements that did not account for such adsorbates.

Bringing it all together with a simple model

Finally, we used a simplified theoretical model to verify whether the capacitance minimum we observe experimentally really corresponds to the surface being electrically neutral, even when the surface is composed of two different sites (atomically flat terraces, and step sites).

The answer was reassuring: Under the specific experimental conditions used, the model suggests this hypothesis is correct. This means that, in this particular context, a relatively simple experimental technique and setup can be used to obtain fundamental understanding of more complex surfaces.

Why this matters for real-world electrodes

Real platinum catalysts are composed of many steps and defects. Our results demonstrate that these step sites are determining for the structure of the electric double layer and the capacitance response we measure.

This has important implications for how we interpret electrochemical measurements. It also serves as a reminder that what happens at the atomic scale can strongly influence what we observe at the macroscopic level.

By building a clearer picture of how water and charge interact at stepped platinum surfaces, we hope this work helps bridge the gap between theory, experiments, and real-world applications.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Chemistry

A monthly journal dedicated to publishing high-quality papers that describe the most significant and cutting-edge research in all areas of chemistry, reflecting the traditional core subjects of analytical, inorganic, organic and physical chemistry.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in