The evil clonal cousins behind relapse in childhood cancer

Published in Cancer and Paediatrics, Reproductive Medicine & Geriatrics

So called "precision oncology" has become a big thing in childhood cancer. This means that treatment decisions are based on molecular fingerprints of tumors, rather than grouping patients together based on similarities on how their tumours appear when looking down a microscope. To achieve this, even smaller countries have set up genomic medicine programs for children with cancer. However, a problem here is that the molecular fingerprints of cancers vary across time and space in a complex fashion.

Our paper is the result of a scientific marathon, starting six years ago. Back then, we published a paper showing that childhood cancers were often genetically heterogeneous and that the pattern of this diversity impacted treatment outcome -- the more genetically diverse and plastic the cancer, the higher the risk of the child dying . However, we had problems finding a method to the ostensible genetic madness of cancer. Especially, we wanted to understand where relapsing tumors really came from. This is a critical issue as childhood cancers that come back are very hard to treat and often kill the patient.

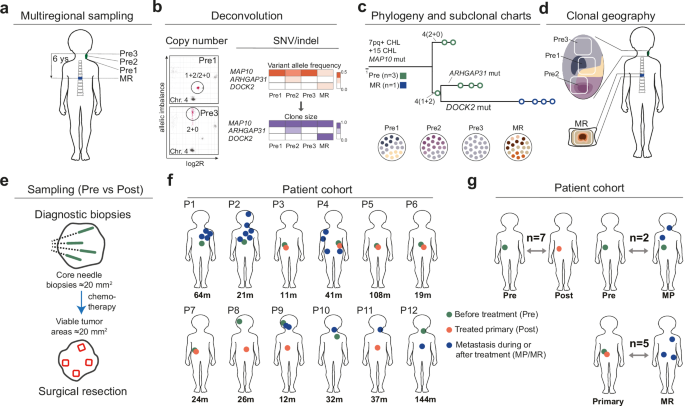

To map the genetic ancestry of cells that survived chemotherapy, we focussed on one of the more common childhood cancers (neuroblastoma) and painstakingly dissected areas of tumor cells that had survived chemotherapy to compare their genomes to samples taken at diagnosis. We had to use very special methods to analyse the fragmented DNA found in pathology archives. We also developed special computer programs to make family trees of childhood cancer cells, showing the genetic links between tumor cells from different locations and time points. This was necessary because the algorithms developed for adult cancers did not account well for the large scale chromosomal variation found in tumors from children.

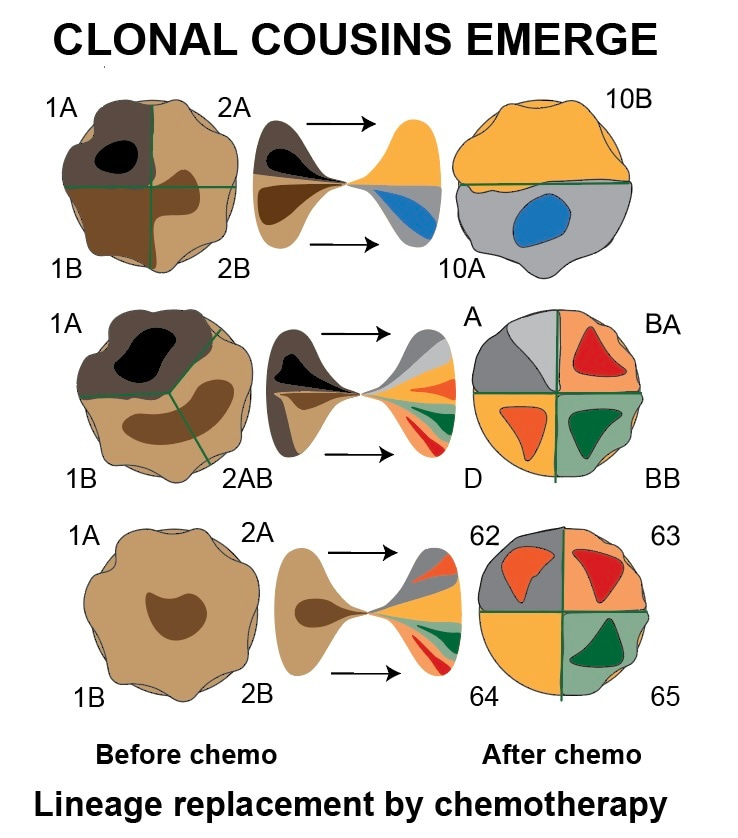

In the end, we could compare the genetic profiles at various stages of disease in-depth in 12 patients, a dataset we supplemented with experiments where we treated cancer cells grown in laboratories to see how their genome changed. The result: cells that survive chemotherapy to grow back again are typically genetic cousins of the cells present from the beginning. What does this mean? First, it means that they share only part of their genomes with the cancer cells present at diagnosis: some mutations are lost, others are added. This is distinct from a parent-daughter relationship between primary tumors and relapses, where mutations are just added.

For practical purposes, it means that relapses must be resampled and analysed again if a doctor wants to have a useful genetic profile of a relapsing neuroblastoma or tumors that resist treatment; the data from the moment of diagnosis will not correctly reflect the mutational profile at later stages. Our paper also gives details on how to perform such sampling as we tracked down how genetically distinct subpopulations of cancer cells distribute over anatomic space at different stages of disease. We were also able to go back in time and understand how these sometimes lethal "clonal cousins" emerged at cancer initiation: from a state of increased tolerance to DNA breaks associated with extra copies of the gene MYCN.

Finally, our long process of two years of revision gave me two insights. First, as a clinician it was new to me that choices of bioinformatic software to solve specific problems may be very subjective and seem to even have an emotional aspect. There is "belief" in certain scripts and a dislike of others, for reasons hard to explain for the outsider and in a way that almost appears to be "matter of taste". Second, the detailed genetic data we can now get even from very small samples made me seriously consider what bad actors could do with the genomes of my patients. That spurned an entirely new, multidisciplinary research project, a biomedical research security course, and a journey by scenario analysis into the darker domains of geopolitics. Should you be interested - that could be the topic of another post.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in