The Feedback Loop of Forest Fires and Land Degradation

Published in Earth & Environment and Sustainability

I study what happens after the last flame is out. The way bare, scorched hillslopes suddenly become vulnerable to rain, how ash-covered soils can be stripped away by the first storms, and how rivers carry this material downstream. This is the “poor relative” of fire management, often overlooked in emergency plans and rarely mentioned in news reports. Yet it plays a crucial role in how fires drive land degradation.

Working with colleagues from around the world led us to understand, that this overlooked phase concerns not just in one catchment or one country, but in fact has global impact. With nearly the area of European Union burning every year, what does that mean for the soil that supports our forests, crops, and source of raw materials? How much of this vital resource is being lost in the months after a fire, and where are the hotspots of post-fire erosion risk?

Our paper, Global Estimation of Post-Fire Soil Erosion, is our attempt to answer these questions. In this post, I want to share the story behind the numbers, the ideas that motivated us, the challenges of “chasing fires” at the global scale, and why I believe that paying attention to the aftermath of fire is essential if we truly want to understand (and manage) the changing fire regimes of our planet.

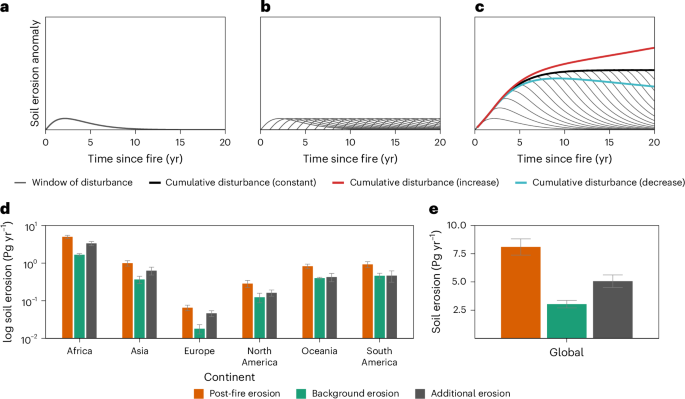

In post-fire science, we often talk about the window of disturbance, the period after a fire when erosion spikes sharply and then gradually declines back to its pre-fire, background levels as vegetation and the litter layer recover. If you imagine a line showing erosion through time, it jumps up right after the fire and then slowly drops until it meets the “normal” line again. This simple idea is widely accepted and has guided many field studies. But in practice, it is much harder to pin down. Different ecosystems recover at very different speeds, and one of the hardest parts to capture is what happens to the soil itself. Many soil impacts can only be detected by physically sampling fire-affected areas, and at the global scale (as in this study) that becomes impossible. Most global indicators we have track vegetation, not soil properties or soil health. On top of that, research tools are limited by time. Typical projects run for three to five years, while the consequences of a severe fire on soils and erosion can last much longer. In other words, the funding cycles we work within rarely match the true duration of the window of disturbance.

Another key concept in our work is burn severity. It is a metric developed to describe how strongly a fire has affected an ecosystem. In simple terms, higher burn severity usually means more damage, including higher erosion risk. When we talk about burn severity in soils, we are referring to the impacts of high temperatures on the topsoil, loss of structure, combustion of organic matter, and the creation of loose, fragile material that is easily mobilized by runoff. Burn severity is widely mapped using remote sensing and has become a cornerstone of many post-fire studies and operational assessments. However, when you walk across a burned area, you quickly see that satellite-based indices do not always capture the full complexity of what happened on the ground. A ground fire smoldering through litter and roots can leave a different legacy to soil than a crown fire that mostly consumes aboveground biomass, even if both end up in the same severity class from space. In the field, burn severity is very evident, but its thresholds are fuzzy, which is why we often work with broad classes such as low, moderate and high, while some teams use five or six classes in detailed surveys. Despite these limitations, the fact that burn severity can be mapped makes it extremely valuable. It becomes an essential input for models, including the global post-fire erosion estimates we developed in this study.

The other idea I keep coming back to is post-fire management. Anyone who knows me has heard me repeat that it should be fully integrated into the fire management cycle, alongside prevention, preparedness and suppression. Yet it is usually the missing piece, rarely planned, rarely funded, and often barely mentioned in strategies or reports. One criticism I have heard as a scientist is that post-fire action doesn’t happen because we have not yet provided the tools, no effective way to support mitigation, nor clear quantitative guidance on where and when to intervene. This work shows that this argument is no longer valid. The tools exist. The real question is whether there is the will to use them.

In previous work that led up to this paper, we looked at the 2017 fires in EU and found that even five years later, roughly half of the burned area had still not returned to background conditions. In most of those places, as far as we could see, essentially nothing was done after the fire. Many countries lean on the idea that natural regeneration is the best option, but I suspect it is often chosen because it is cheaper, not because it always leads to the best outcomes for soils and ecosystems. We can act, and we can do better. The tools we bring together in this study offer a global framework that can support post-fire management. Even if the data are imperfect, they provide meaningful indicators to prioritize where intervention is most needed. Decisions must be made quickly (ideally within the first 45 days after a fire) which makes robust, ready-to-use information essential. With this work, we show that it is possible to deliver such information at both local and global scales, and that the excuse of “no tools available” should no longer delay post-fire interventions.

So what did we actually do in this study that speaks to these issues? One of my first hopes was that, with nearly 20 years of data, I would finally be able to see a clear, global expression of the window of disturbance, a sort of “average” recovery time, even if it varied across biomes, climate regions or ecosystem types. I imagined that, at least in a statistical sense, the peak-and-recovery pattern would emerge. It didn’t. After a lifetime spent chasing the most accurate window of disturbance model, even a two-decade global dataset did not give me a clear answer. This tells me that more research is needed, but it also suggests something else, which we discuss in the paper. Many of the ecosystems we are looking at may already be under heavy pressure from land degradation and even desertification, and some may have shifted to alternative states after repeated disturbances. These disturbances do not need to be back-to-back fires. They can be separated by years, combined with droughts, land-use changes or other stressors. Over time, vegetation dynamics can change so much that, when we look at one particular fire, we are really seeing the legacy of a much longer disturbance history. From that perspective, the “missing” window of disturbance may actually be a sign that the baseline itself has moved. This was not the clean answer I was searching for, but it is a powerful and, I believe, very relevant hypothesis emerging from this work.

Another key step in our work was to move beyond the idea of a single fire in a single year. Most erosion studies report values in tonnes per hectare per year (a metric derived from agricultural land) implicitly treating each disturbance as if it were isolated in time. But fires leave a legacy, and their impacts on soils and erosion can last for several years. In this study, we explicitly accounted for the cumulative effect of multiple fires worldwide, so that the erosion attributed to a given year includes not only the most recent burns, but also the lingering effects of older ones whose soils are still recovering. When we separated the contribution of the most recent fires from the legacy of previous ones, we found that, in a given year, only about 31% of post-fire erosion is linked to the latest fire event, the remaining comes from older burns still echoing through the system. This shows very clearly that, even though erosion peaks immediately after a fire, its long tail is just as important.

We also wanted a way to put these numbers into perspective, so we compared post-fire erosion with soil erosion from agriculture, the land use that most people instinctively associate with erosion, and one where management is, at least in principle, possible. Under our metric, we found that global post-fire soil erosion corresponds to about 19% of the erosion from all land and around 35% of the erosion from agricultural land. This gives a sense of the scale and magnitude of the problem. Fire is not a marginal process, but a major, quantified driver of land degradation that should be fully recognized in global assessments and management strategies.

Looking ahead, I believe we need to look much more closely at land degradation and how wildfires contribute to it. For me, this link is now undeniable, but we still lack good indicators. We need robust, global metrics of soil health, ideally combining satellite imagery with targeted field surveys, and we need better ways to translate what we see from space into what is actually happening in the soil. We also need to understand how different disturbances, fires, droughts, land-use change and others, interact to push ecosystems towards degradation or even alternative states. Only then can we properly place wildfires within the broader disturbance portfolio affecting the land.

On the post-fire side, our study focused on soil displacement, but many questions remain. We still need to quantify how this erosion translates into impacts on water bodies, on infrastructure, and ultimately on the costs that societies pay (often silently) in the years after a fire. Right now, by not implementing mitigation measures after fire, we are essentially betting on luck, hoping that no intense storm hits at the wrong time, or that downstream systems can absorb the ash load and extra sediment. How many of these costs are we failing to prevent? If we can better understand and quantify them, and link them to concrete management options, we can move from reacting to disasters towards actively improving the resilience of our forests and landscapes in a world where wildfires are here to stay.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Geoscience

A monthly multi-disciplinary journal aimed at bringing together top-quality research across the entire spectrum of the Earth Sciences along with relevant work in related areas.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Past sea level and ice sheet change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Urban fires around the globe

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in