The global conservation movement is diverse but not divided

Published in Sustainability

During this period, debates within the conservation community have taken on a new level of intensity and, at times, acrimony. In 2012, Peter Kareiva and Michelle Marvier published a manifesto for ‘new conservation’, which is motivated by delivering benefits of biodiversity to people and supports working in partnership with corporations. Michael Soulé and others strongly rejected this view, arguing that conservation should be motivated by the intrinsic value of biodiversity, should focus on protected areas, and should reject working with capitalism.

Various commentators have argued that this ‘new conservation debate’ has been too hostile, too dominated by a narrow demographic group, and too simplistic in its portrayal of conservation views as a binary choice. We conducted an initial study of the views of conservationists on the issues raised in this debate at the International Congress on Conservation Biology in Montpellier in 2015, using Q methodology. The results suggested that there were indeed multiple different perspectives on these issues within the conservation community.

Conveniently for us, on the first day of the Montpellier conference there was a plenary debate on the new conservation in front of a packed hall. Peter Kareiva went first, setting out his arguments for new conservation. In response, Clive Spash, an ecological economist, argued against working with business to achieve conservation, drawing on ideas from economics and social theory. What was striking was that his was not a conservation biologist’s argument in favour of protected areas. Rather, it was a critical social science perspective, supportive of conservation for the benefit of people but against using the tools of capitalism. As you can see from the image, Spash’s speech was enthusiastically received by large sections of the audience, who gave him a standing ovation. However, others in the audience were horrified, and didn’t even clap. Disagreements in the conservation community could not have been made clearer.

Several of us were in the room for the debate that day, which proved a real turning point in our research, for two reasons. First, we were amazed to see the response to Spash’s arguments, which were distinct from those present in the mainstream new conservation debate but clearly resonated with many in the audience. Second, seeing so many people in the room energised by the issues, we asked ourselves ‘why not scale up our research and go for a global survey of the conservation community’?

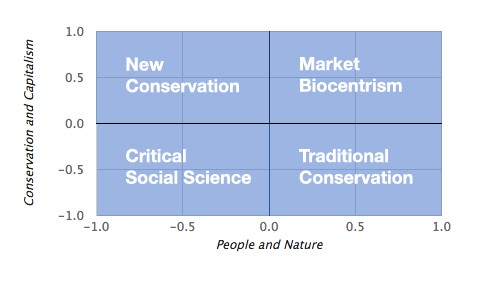

It is from this moment that the Future of Conservation Survey was born. We took our Q methodology survey and converted it into an online survey of the conservation community, with the addition of some demographic questions. Crucially, we created a mechanism for instant feedback for respondents, presenting them with a simple XY scatter plot showing them roughly which kind of conservation perspective best aligned with their answers.

The response was overwhelming. Within days of the launch of the survey in April 2017 we had several thousand respondents, and at the time of writing the number is approaching 15,000 from over 160 different countries.

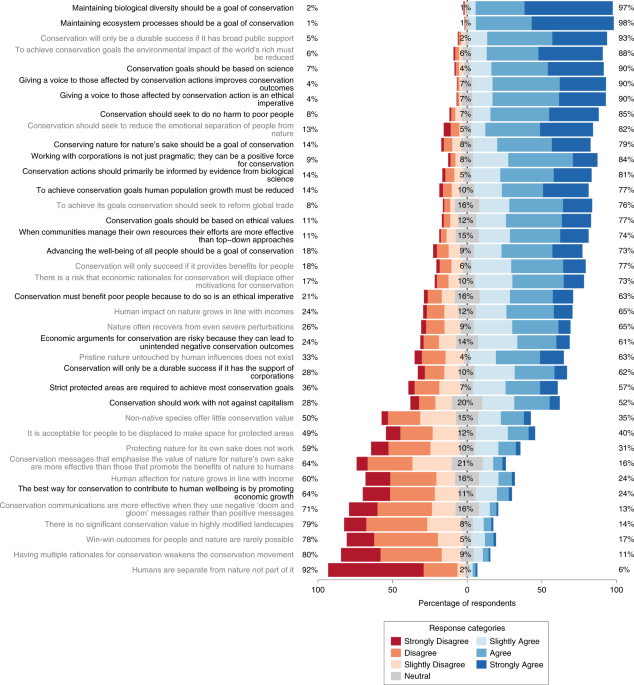

After recruiting a stats expert as a co-author to cope with the large dataset, we have crunched the numbers and the results are now published in Nature Sustainability. We have found that although conservationists hold a very wide range of views, there are many core issues on which there is a high level of consensus, and the distribution of views does not fall into two or more distinct clusters. Hence the title of the paper – the global conservation movement is diverse but not divided. At the same time, there are distinct associations between views and demographic characteristics (such as gender and nationality). This demonstrates the importance of ensuring that debates on the future of conservation include conservationists who represent the diversity that exists within the sector.

In making this call for diversity we freely acknowledge that we the researchers on this project are not a very diverse group – we are all white Europeans, four men and one woman. However, we hope that by conducting this research we have succeeded in bringing to the debate the views of a much more diverse group of over 9000 conservationists from all around the world. We are continuing to seek ways to improve the diversity of respondents, initially by translating the survey and website into additional languages.

As an unexpected bonus, soon after the Future of Conservation Survey went live, we began to be contacted by academics and practitioners telling us that they had used the survey as a tool for exploring the views held by those they worked with, such as their colleagues or students. This suggested an opportunity to use our survey for teaching and capacity development. We are now developing a free web-based tool called GO-FOX that allows anyone to use the survey in this way, and we hope that you will use it!

We have greatly enjoyed working together on this project, and hope that the results will make a significant contribution to the conservation community as it wrestles with crucial questions about what, why and how to conserve.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Sustainability

This journal publishes significant original research from a broad range of natural, social and engineering fields about sustainability, its policy dimensions and possible solutions.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in