The neural signature of psychomotor disturbance in depression

Published in Neuroscience, Protocols & Methods, and General & Internal Medicine

Explore the Research

The neural signature of psychomotor disturbance in depression - Molecular Psychiatry

Molecular Psychiatry - The neural signature of psychomotor disturbance in depression

What we already knew and what was missing

Major depressive disorder is a very common health problem that affects at least one in five persons at least once in their lifetime. Only half of the patients with depression get well with the first antidepressant treatment administered and up to a third of all patients with depression do not respond to subsequent treatment approaches. One possible explanation for this great variance in treatment response is that depression is a very heterogeneous syndrome with multiple potential symptoms included. One frequent symptom that has been linked to poor treatment response is psychomotor disturbance. This includes psychomotor retardation or slowing that is characterized by a reduction or slowing of movements and activities, and psychomotor agitation that is characterized by increased movement, activities, and restlessness.

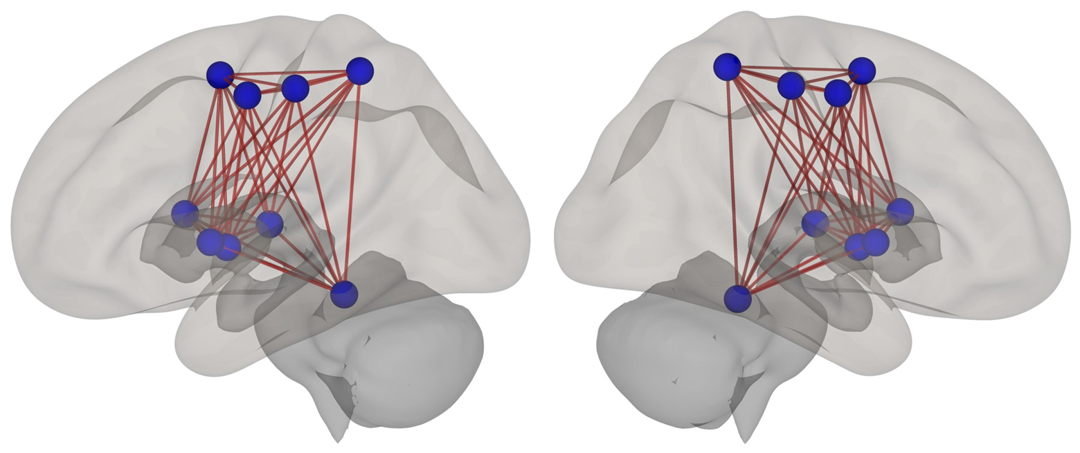

Today, we have no specific treatment for psychomotor disturbance in depression, yet. We also only have limited knowledge about what happens in the brain when patients have psychomotor disturbance. We know that alterations in the fibers connecting different brain regions and changes in the activity of brain regions responsible for motor behavior are related to psychomotor slowing. But no study has examined whether there are changes in patients with depression and psychomotor disturbance with regards to functional connectivity, i.e., how closely the different brain regions of the motor system work together. We can estimate this connectivity by measuring the similarity of the spontaneous neural activity of brain regions with functional magnetic resonance imaging sequences.

What we did in our study

In our study, we measured the functional connectivity between multiple brain regions of the motor network and compared it between healthy participants and participants with depression and either no psychomotor disturbance, psychomotor slowing only, psychomotor agitation only, or concurrent slowing and agitation. We also examined whether patients with psychomotor disturbance had more severe depression or other impairments than patients without psychomotor disturbance. Summarizing the existing research, we recently found that psychomotor disturbance might still be present in patients who are not depressed anymore. Therefore, we also performed these comparisons in previously depressed but currently remitted participants.

What we found in the behavior...

We found that more than half of the patients with current depression and one in six of the previously depressed participants had some form of psychomotor disturbance. Patients with psychomotor disturbance did not have more severe depression than the patients without psychomotor disturbance. But they had poorer global functioning, i.e. participants with psychomotor disturbance – on average – cannot function as well in their community as participants without psychomotor disturbance. This difference was even more pronounced in participants who were not depressed anymore. This means that people who have psychomotor disturbance but are not depressed anymore, still have problems that make their life harder. Therefore, they might profit from a treatment that can target psychomotor disturbance specifically.

…and in the brain

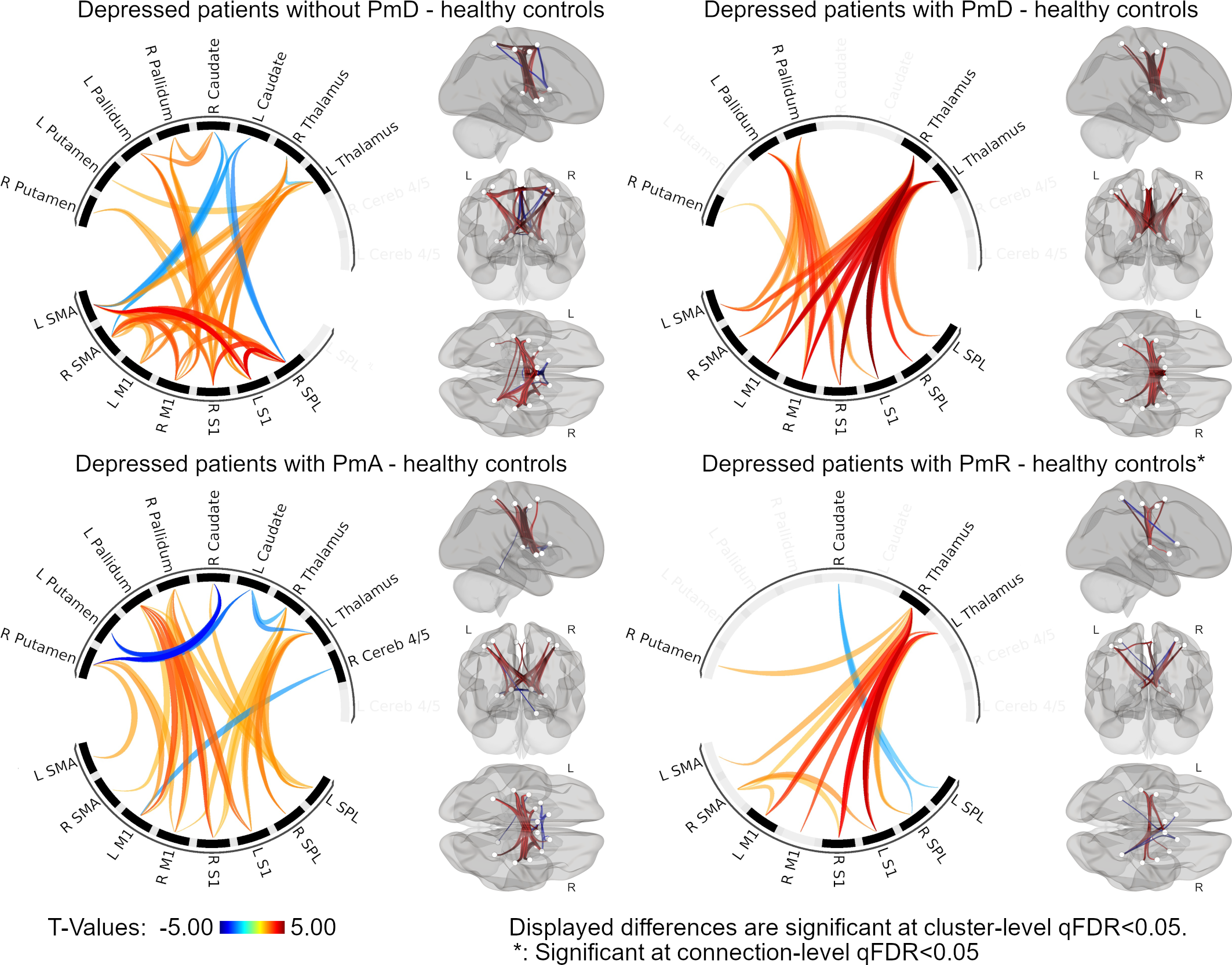

Regarding the differences in functional connectivity, we found no differences between the previously depressed participants and the other groups. When we compared the currently depressed patients with the healthy participants, we found that the ones who had psychomotor slowing had higher connectivity between the thalamus and primary sensorimotor cortex. Those who had psychomotor agitation had higher connectivity between the pallidum and the sensorimotor cortex. Finally, the patients without psychomotor disturbance combined the changes of psychomotor slowing and agitation and additionally had higher connectivity between multiple cortical regions.

This means that psychomotor slowing and psychomotor agitation have distinct neural signatures, but both lack the same change that we only found in the patients without psychomotor disturbance. We assume that this change can compensate the higher connectivity between the sensorimotor cortex and thalamus or putamen and thus prevents psychomotor disturbance.

Where to go from here?

In general, it is possible to influence the functional connectivity between brain regions with non-invasive brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation. While these stimulation techniques fail to reach deep brain regions far from the surface of the skull, fortunately, the regions in which we would like to change connectivity are easily accessible by these stimulation techniques.

In summary, our study shows that there is a need for the treatment of psychomotor disturbance even in individuals that are no longer depressed, and one possible approach for such a treatment could be to influence the functional connectivity between the cortical brain regions of the motor network with non-invasive brain stimulation techniques.

Follow the Topic

-

Molecular Psychiatry

This journal publishes work aimed at elucidating biological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders and their treatment, with emphasis on studies at the interface of pre-clinical and clinical research.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in