The Story Behind Our Study on Childhood Fractures

Published in Surgery

As orthopedic surgeons and researchers, we see these injuries every day. But when we stepped back, one big question arose: *what do we actually know about childhood fractures, and who is shaping that knowledge?* That simple question became the seed for our study.

Why We Asked This Question

Medical science moves forward because of research—studies done in hospitals, labs, and universities that help doctors understand diseases and improve treatments. But not all studies have the same impact. Some become milestones—highly cited by other researchers and doctors because they offer powerful insights, useful techniques, or new directions.

In the case of pediatric fractures, we realized that while thousands of papers had been written, nobody had put together a clear picture of which ones shaped the field the most. Which countries were leading the way? Which doctors and hospitals had made the biggest contributions? Were there gaps—places or topics that were under-researched?

Answering these questions matters. For a parent, it could mean that the technique used to fix their child’s broken arm was developed decades ago by a study in another part of the world. For policymakers, it shows where investments in child health are paying off, and where more work is needed. For young doctors, it highlights the giants on whose shoulders they stand.

How We Did It

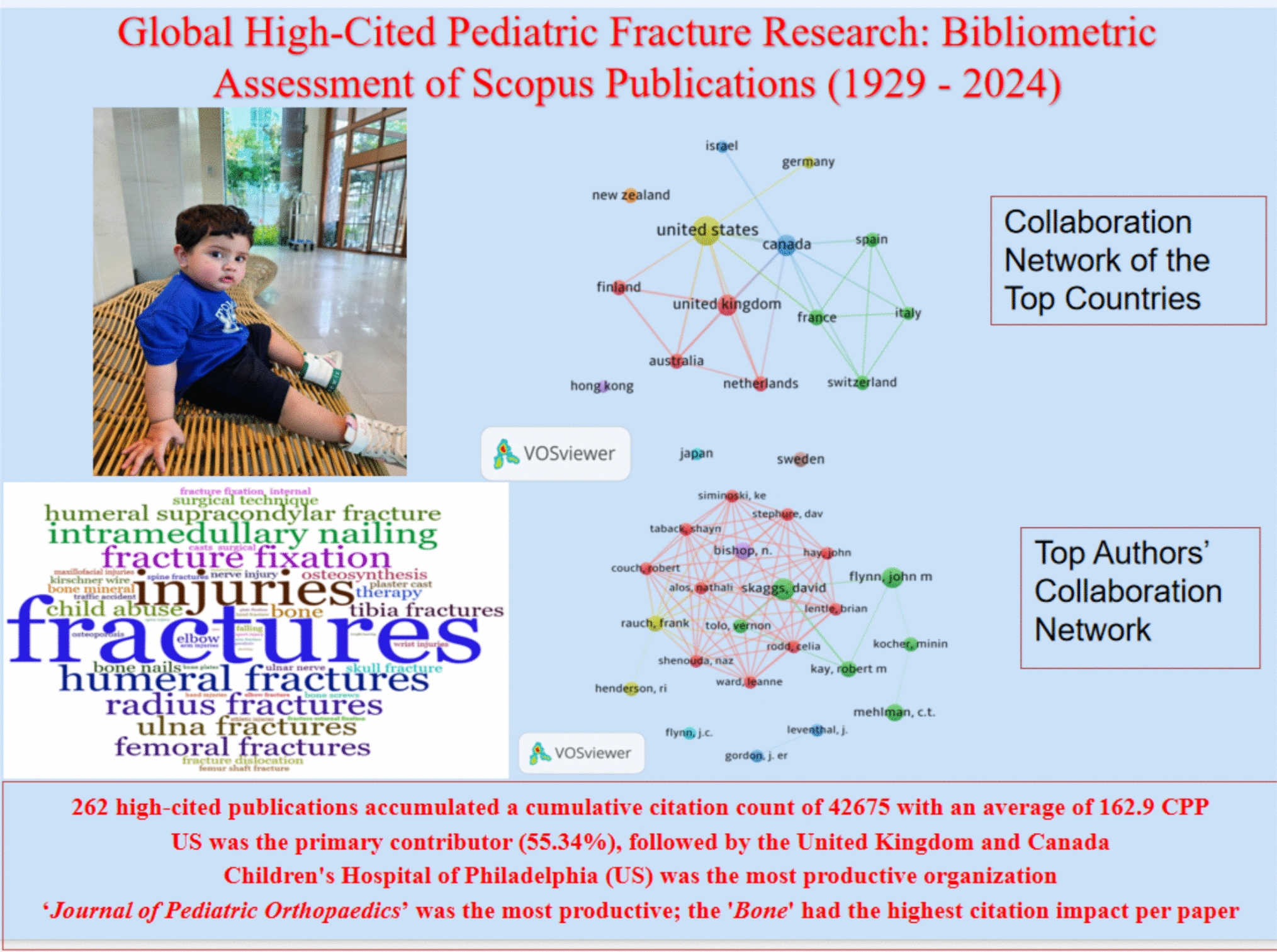

Our team decided to look at nearly a century of research, from 1929 all the way up to 2024. We used a massive database called *Scopus*, which is like a global library of scientific papers. Out of over 12,000 papers on childhood fractures, we focused on the “highly cited” ones—those that had been referenced 100 times or more by other researchers. These 262 papers represent the backbone of global knowledge in pediatric fractures.

We didn’t just collect them. We analyzed them using advanced bibliometric tools (think of them as maps for research). These tools helped us track patterns: who wrote the papers, which hospitals or universities they came from, which countries collaborated, and even which keywords—like “forearm fracture” or “child abuse”—kept recurring.

It was like piecing together a giant puzzle of global medical history.

What We Found

The results were eye-opening.

A century of research: Between 1929 and 2024, only 262 papers on childhood fractures became highly influential, together gathering more than 42,000 citations.

- A few countries dominate: The United States led the way with over half of all influential papers. The UK and Canada followed. Surprisingly, not a single highly cited paper came from India or China, even though these two countries have the largest child populations in the world.

- Famous hospitals lead the pack: The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Boston Children’s Hospital, and The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto were among the most active contributors. These names are familiar to many in the medical community, but now we saw their enormous impact laid out in numbers.

- Which fractures matter most: Forearm fractures, femur (thigh bone) fractures, and humerus (upper arm bone) fractures were studied the most. Together, they made up more than half of all influential research.

- Shifts in focus over time: Earlier papers dealt with understanding fracture patterns and risks, like how often they happen or how nutrition plays a role. Later studies shifted to surgical techniques—like new ways to pin bones or use elastic nails for femur fractures.

One fascinating detail was about collaboration. Papers that involved researchers from multiple countries were cited much more often, showing that when minds come together across borders, the results are stronger and more useful.

Why It Matters Beyond Medicine

At first glance, this might sound like a study only doctors would care about. But the bigger picture is about children’s health and wellbeing worldwide.

For example, fractures aren’t just random accidents. They can sometimes be a red flag for child abuse. They can also be linked to conditions like poor nutrition, obesity, or diseases that weaken bones. If we know where the best research is happening, and what it tells us, we can make better policies, guide parents on prevention, and ensure that hospitals everywhere adopt the best treatment practices.

Another big issue is "equity". Our study highlighted that while North America and Europe dominate research, countries like India—with 472 million children—have not produced highly cited global papers in this field. That’s not because children here don’t get fractures (they do, often in alarming numbers), but because research from these regions isn’t getting the visibility or funding it deserves. This gap matters, because healthcare solutions in India or Africa might need to be different from those in the US. Children’s diets, activity patterns, and access to hospitals vary greatly.

By shining a light on this imbalance, we hope to encourage more international collaboration and investment in low- and middle-income countries. If globally recognized research starts emerging from these places, it will directly benefit millions of children.

The Human Side of Numbers

While our paper is full of charts, graphs, and statistics, at its heart it is about children like those in our neighborhoods.

Think of a ten-year-old boy who breaks his forearm falling off a bicycle. The treatment he receives today—whether the doctor chooses a cast, surgery, or a pinning technique—is influenced by decades of studies we analyzed. Or picture a little girl in a rural area where malnutrition makes her bones fragile. Research into the role of calcium and Vitamin D in childhood fractures directly informs how her condition is understood.

Every data point in our study connects back to a real child, a real family, and a real journey of healing. That’s what makes this work so meaningful.

Looking Ahead

Our paper is not the end of the story—it’s a beginning. By mapping where we stand, we can now see where we need to go.

- Encouraging global partnerships: The evidence is clear—collaboration produces better science. We hope more hospitals in India, Africa, and Asia will work with global partners.

- Focusing on prevention: With half of all children expected to break a bone before they turn 18, prevention through safe play environments, better nutrition, and awareness is critical.

- Investing in local research: Policymakers and funders should realize that children in India or China deserve the same level of research-based care as those in the US or UK.

- Exploring long-term effects: Many questions remain unanswered—do childhood fractures increase the risk of adult fractures? How do lifestyle changes (like more screen time and less outdoor play) affect bone health?

By addressing these, the next generation of studies could make an even greater difference.

Our Message to the Community

For families, this study is a reminder that childhood fractures are common but also well understood thanks to decades of research. Treatment has improved enormously, and outcomes are usually excellent. At the same time, prevention—through safe play, healthy diets, and attentive care—remains vital.

For young doctors and researchers, it shows the shoulders of giants they are standing on, and points to the gaps they can help fill.

And for policymakers, it underscores the urgent need to support pediatric orthopedic research, especially in countries where children make up the largest share of the population.

In the end, the story of pediatric fracture research is not about bones alone—it is about protecting childhood itself. Every broken bone that heals well allows a child to return to play, to school, and to life with confidence. By learning from the past 95 years of research, and by working together across countries and disciplines, we can ensure a safer, healthier future for children everywhere.

Follow the Topic

-

Indian Journal of Orthopaedics

This is the official publication of the Indian Orthopaedic Association, focusing on clinical orthopaedics and basic research.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in