"This Is Where Life Left Us": Place Attachment and Duress and Rethinking ‘Home’ in Rough Neighbourhoods

Published in Social Sciences, Sustainability, and Philosophy & Religion

The Story Behind the Research

It began with a whisper in the wind-blown outskirts of Norton town, Zimbabwe. “This is where life left us,” an old man murmured outside his collapsing shelter in Lydiate informal settlement. That utterance anchored me. It wasn’t just sadness I heard, it was a quiet philosophy of survival. It sparked the research that eventually became the article “Place Attachment under Duress: Chronic Illness, Statelessness, Poverty and Spatial Entrapment among Migrants in Rough Neighbourhoods.”

As a scholar of urban migration and marginality, I’ve long been drawn to the politics of dwelling. But this time, it wasn’t about movement, diaspora, or transnational ties. It was about people who couldn’t move, who were trapped in place, ageing and infirm in neighbourhoods where neither the past nor future seemed to belong to them.

Listening to Voices from the Margins

I spent over two years conducting ethnographic research in Lydiate, a rough peri-urban enclave near Norton, Zimbabwe, inhabited largely by Malawian-descended migrants. I engaged with 25 participants, many in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, suffering from chronic illnesses, social invisibility, and profound poverty. They told stories of being stateless, of working Zimbabwe’s farms for decades and still being labeled “alien.” They spoke of “resigned emplacement”—the notion of settling in places not because they chose to, but because there was nowhere else to go.

They welcomed me into their homes of mud, thatch, and memory, offering not just tea or space on a stool, but their pain, dignity, and the intimate architecture of survival.

Theoretical Lenses and Conceptual Innovations

Migration studies typically focus on movement; how people cross borders, maintain fluid identities, and stay connected to multiple “homes.” But what happens when the border is internal, and people are immobilized by ageing, illness, or exclusion?

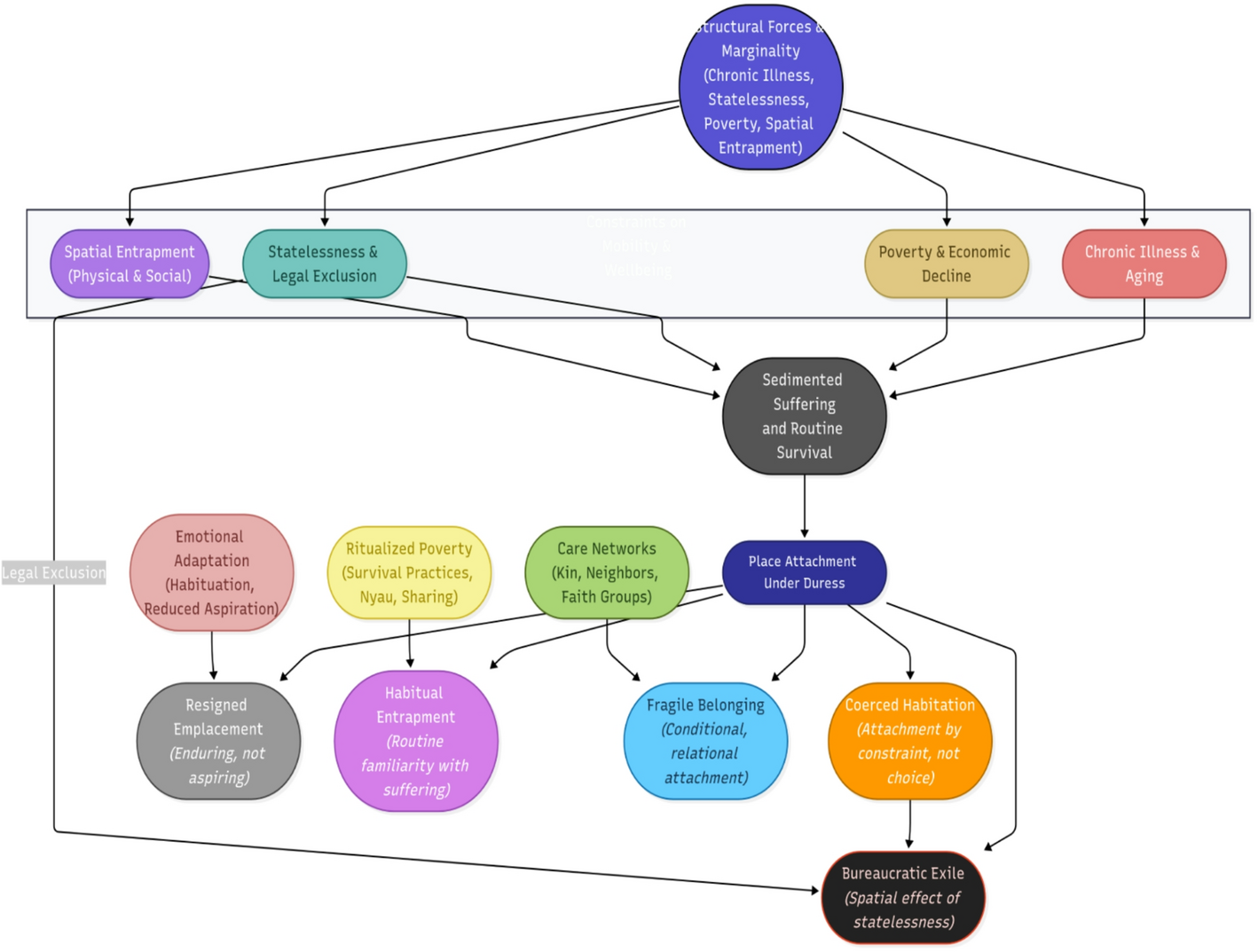

In this study, I develop the idea of “place attachment under duress.” Unlike traditional understandings of home as a site of nostalgia or belonging, here, home is endured. I propose concepts like:

- Involuntary Home: A place inhabited not out of desire, but because of structural abandonment.

- Resigned Emplacement: The long-term settling into places you never planned to stay, because exit is impossible.

- Habitual Entrapment: A cycle of inherited poverty and constrained mobility passed down generations.

Together, these ideas challenge romanticised notions of ‘home’ and force us to confront how exclusion, illness, and statelessness create new geographies of immobility.

Challenges in the Field

Conducting research in Lydiate was emotionally intense. Many participants were frail, some close to death. Ethical dilemmas emerged: How do you ask someone about ‘home’ when they know they might die in that place, not out of choice, but because no one else will have them?

Trust was hard-earned. As an outsider, I had to acknowledge my privilege, my ability to leave. I kept a reflexive journal to process the emotional weight of what I heard: mothers burying sons in unmarked graves, elderly couples surviving on grass sales, and young orphans parenting younger siblings in huts that fall apart each rainy season.

Key Findings

Three generations of migrants in Lydiate: elderly, middle-aged, and youth are stuck in a place they neither fully reject nor embrace. The elderly suffer from legal invisibility and health decline, staying because they are too weak to leave. The middle-aged are weighed down by caregiving duties, stuck between ailing parents and dependent children. And the youth inherit this poverty and spatial immobility, seeing no path to escape.

And yet, amidst all this, they build meaning. Through rituals like the Nyau cult, informal care, and small daily victories, they construct a moral economy of survival. Their home may be involuntary, but it is made livable through endurance, routine, and collective care.

Why It Matters

Why should this story matter beyond Lydiate?

Because Lydiate is not an anomaly. Across the Global South, rough neighbourhoods are expanding. These are not just “slums” or “informal settlements.” They are zones of bureaucratic exile, where people live outside the margins of legal, economic, and healthcare systems.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities) cannot be achieved if we ignore places like Lydiate and the people left behind in policy shadows.

Urban planning, migration policy, and public health must confront the politics of forced sedentarism, where people don’t migrate because they cannot, not because they’re rooted. It’s time we count those who aren’t moving.

Reflections and Hopes

I hope readers, whether they are urban planners, students, neighbours, or policy advocates, can pause and reflect on what it means to be "home" in a place no one planned to stay. I want us to ask:

- What makes a place liveable when legal status, health, and resources are stripped away?

- How do we design cities that care for those who can’t move, who are growing old and invisible?

Let’s widen the lens of migration studies, expand the moral responsibilities of planning, and reimagine what it means to belong in cities that grow by forgetting.

A Note to Fellow Researchers

To those studying marginality, displacement, or rough neighbourhoods: keep listening. Often, the most powerful theories come not from textbooks but from cracked walls, whispered regrets, and the quiet courage of those who endure.

Be reflexive. Take care of yourself. And never assume mobility is synonymous with agency. Stillness can be just as political.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Sustainability

A multi-disciplinary, open access, community-focussed journal publishing results from across all fields relevant to sustainability research whilst supporting policy developments that address all 17 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Economic Responses to Environmental Challenges: Evidence, Models, and Innovations

Environmental degradation, climate change, and resource scarcity have emerged as critical global challenges, posing significant threats to economic stability, public welfare, and sustainable development. These complex issues require not only technological innovation and policy reform but also a deep understanding of the economic mechanisms that drive environmental outcomes.

In response, this Collection focuses on how economies can effectively address these threats through data-driven research, advanced modeling, and strategic policy design. The issue brings together studies that apply econometric and statistical methods—such as time series analysis, panel regression, spatial econometrics, and simulation-based models like Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) and Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models—to assess environmental policies and measure their economic impacts. These analytical tools are used to quantify trade-offs, predict long-term outcomes, and guide decision-making under uncertainty. By bridging economics, environmental science, and public policy, this collection deepens the empirical and theoretical understanding needed to design effective responses. It strengthens the foundation for achieving environmental sustainability alongside economic resilience.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Artificial Intelligence and Digital Innovation in Advancing Sustainable Development Goals

This Collection is expected to explore the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and digital innovation in improving progress toward the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). We aim to highlight interdisciplinary research, technological breakthroughs, and practical applications that leverage AI-driven tools, data science, and digital systems to tackle global challenges such as poverty, climate change, healthcare, education, and sustainable infrastructure. This Collection provides a platform for advancing responsible and inclusive innovation by closely bridging technology and sustainability.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 9, SDG 11, SDG 12, SDG 13 & SDG 16

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Digital Innovation, Sustainable Development Goals, Smart Technologies, Data Science, Climate Action, Ethical AI, Smart Cities, Digital Transformation.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Superb paper. Congratulations.