Adapting from Below: Flooding, Informality, and the Power of Community Resilience

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Sustainability

The Story Behind the Research

The seeds of this research were planted during my fieldwork in Cape Town's informal settlements, where I walked through flooded footpaths, listened to residents’ survival stories, and observed grassroots ingenuity in real time. I remember standing ankle-deep in water in Khayelitsha after a storm, watching a group of women redirect stormwater with makeshift tools: stones, sticks, and plastic sheets. What struck me wasn’t just the devastation but the dignified defiance: “We can’t wait for the city; we adapt or drown.”

That moment stayed with me. It raised deep questions: What forms of adaptation are emerging from below? How do vulnerable communities cope, respond, and rebuild, often without external help? And what can the world learn from these frontline actors?

Listening to Voices from the Margins

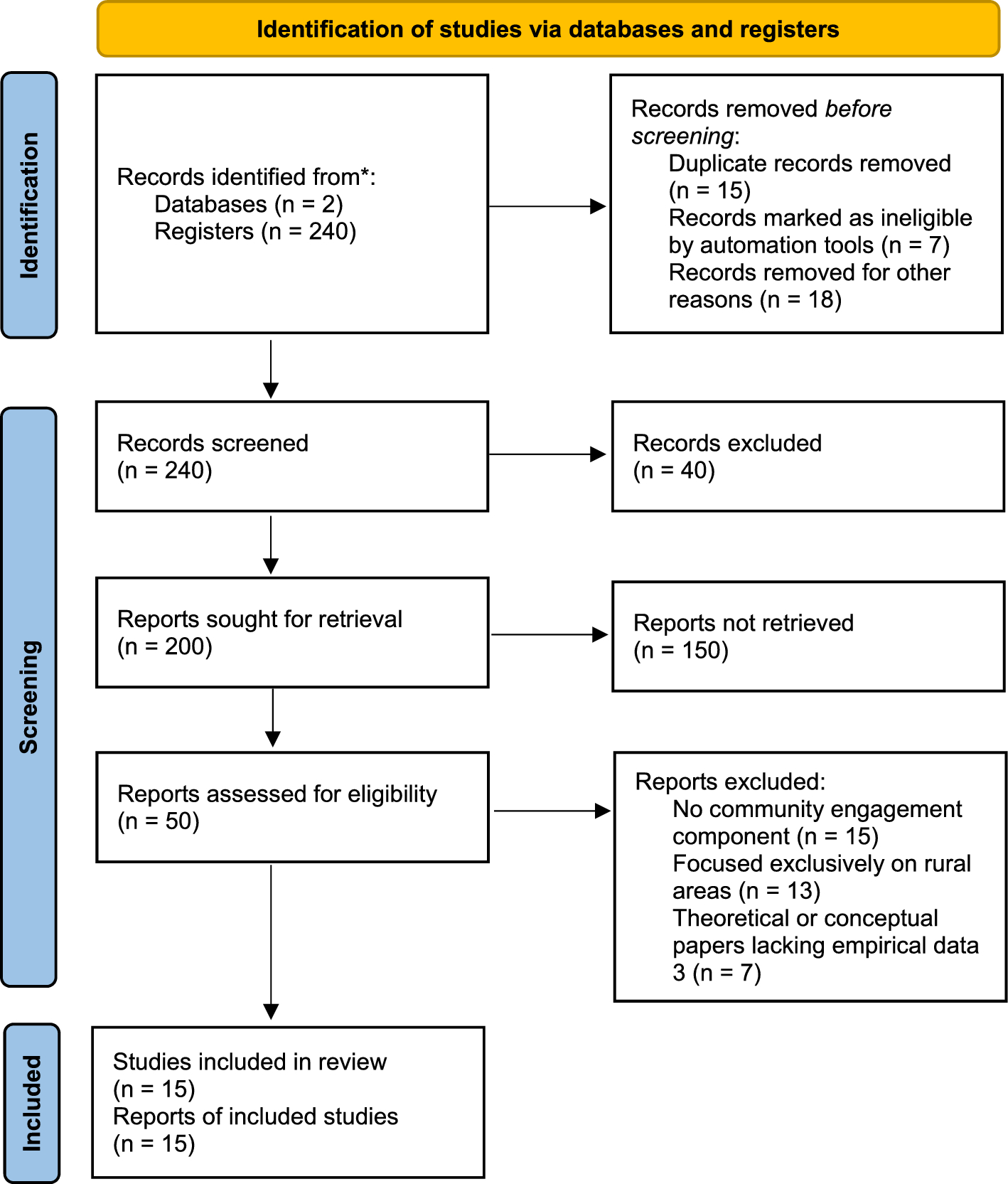

My study looked at 15 case studies across Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, with countries like South Africa, Kenya, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Fiji providing insights into diverse flood-prone informal settlements. These settlements are often located on floodplains, wetlands, or unstable slopes: places deemed unworthy of investment.

And yet, they pulse with agency. Whether through community-led reblocking in Cape Town, bamboo stilt housing in Jakarta, or digital storytelling in Kibera, residents are not waiting for saviours. They are designing their own adaptive futures.

Theoretical Lenses and Conceptual Innovations

At the heart of this study is the concept of Community-Based Adaptation (CBA) - a bottom-up approach that empowers communities to identify, prioritise, and implement flood responses tailored to their needs. But CBA is more than just participation. It is a political act, a reclaiming of power and space in cities that too often marginalise the poor.

I also engage with ideas of:

- Participatory resilience: Resilience shaped with, not for, communities.

- Environmental justice: Recognising that flooding isn’t just natural, it's also political.

- Localism and place-based knowledge: Treating community members as experts of their own environments, not passive victims.

- Urban political ecology: Viewing flooding as a product of socio-political processes, not just climate.

Challenges in the Field

Studying adaptation in informal settlements is emotionally demanding. You witness the violence of neglect, children playing beside overflowing drains, elders losing belongings year after year. But there's also ethical complexity. How do you document suffering without sensationalising it? How do you honour local knowledge while still critiquing systemic failures?

The research also revealed governance gaps. In many cases, promising community initiatives were stifled by bureaucratic inertia, legal exclusion, or a lack of sustained funding. It’s difficult to build resilience on a foundation of precarity.

Key Findings

The study found that communities are adapting in three broad ways:

- Physical and infrastructural solutions: Like raising houses on stilts, creating local drainage channels, or community-led reblocking.

- Social and cultural practices: Savings groups, youth storytelling platforms, and indigenous knowledge (e.g., traditional flood prediction methods).

- Digital and institutional innovations: Early warning systems via mobile phones, community radio, and participatory mapping tools.

However, the success of these measures depends on key enablers: trust, social cohesion, institutional support, and resource access.

Why It Matters

This research challenges the myth that poor communities are helpless in the face of climate disasters. Instead, it reframes them as leaders in innovation and resilience. But their efforts often remain fragmented and under-resourced. Unless their strategies are integrated into city-wide planning and supported with adequate funding, the burden of adaptation will continue to fall unfairly on those least responsible for the climate crisis.

In an era of growing climate risks, the sustainability of cities hinges not only on green infrastructure but also on inclusive governance, where the knowledge, voices, and capacities of the urban poor are recognised as essential.

Reflections and Hopes

What I hope readers take away is this: adaptation is not just about sandbags and storm drains. It’s about power, equity, and belonging. Floods expose more than infrastructure gaps; they expose deep social fractures—who counts, whose homes are protected, whose lives are rebuilt.

We need to centre justice in climate adaptation. Not as an afterthought, but as the starting point.

A Note to Fellow Researchers

To those working in similar contexts: your work matters. But tread carefully. Do not just extract stories, build relationships. Stay longer. Return if you can. Pay attention to silences. Let your writing carry the dignity of those who trusted you with their lives.

Also, share your findings with communities, not just about them. Research should not stop at publication; it must ripple back to where it began.

Call to Action

- For planners: Design with, not for, communities.

- For policymakers: Recognise informal settlements as part of the city, not its margin.

- For donors: Fund grassroots-led projects with long-term commitments.

- For the public: Don’t dismiss “slums” as chaotic or hopeless. They are vibrant, self-organising, and full of lessons on how to live with crisis.

Floods will continue to come. But resilience is already there hidden in alleyways, encoded in community networks, whispered in songs and stories of survival. Our task is to recognise it, nurture it, and stand in solidarity with those already adapting from below.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Sustainability

A multi-disciplinary, open access, community-focussed journal publishing results from across all fields relevant to sustainability research whilst supporting policy developments that address all 17 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Economic Responses to Environmental Challenges: Evidence, Models, and Innovations

Environmental degradation, climate change, and resource scarcity have emerged as critical global challenges, posing significant threats to economic stability, public welfare, and sustainable development. These complex issues require not only technological innovation and policy reform but also a deep understanding of the economic mechanisms that drive environmental outcomes.

In response, this Collection focuses on how economies can effectively address these threats through data-driven research, advanced modeling, and strategic policy design. The issue brings together studies that apply econometric and statistical methods—such as time series analysis, panel regression, spatial econometrics, and simulation-based models like Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) and Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models—to assess environmental policies and measure their economic impacts. These analytical tools are used to quantify trade-offs, predict long-term outcomes, and guide decision-making under uncertainty. By bridging economics, environmental science, and public policy, this collection deepens the empirical and theoretical understanding needed to design effective responses. It strengthens the foundation for achieving environmental sustainability alongside economic resilience.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Artificial Intelligence and Digital Innovation in Advancing Sustainable Development Goals

This Collection is expected to explore the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and digital innovation in improving progress toward the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). We aim to highlight interdisciplinary research, technological breakthroughs, and practical applications that leverage AI-driven tools, data science, and digital systems to tackle global challenges such as poverty, climate change, healthcare, education, and sustainable infrastructure. This Collection provides a platform for advancing responsible and inclusive innovation by closely bridging technology and sustainability.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 9, SDG 11, SDG 12, SDG 13 & SDG 16

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Digital Innovation, Sustainable Development Goals, Smart Technologies, Data Science, Climate Action, Ethical AI, Smart Cities, Digital Transformation.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in