Rising Waters, AI and Smarter Cities – But Are They Just?

Published in Earth & Environment, Research Data, and Sustainability

The Story Behind the Research

The inspiration for this study grew from field visits to flood-prone informal settlements in cities like Cape Town and Harare, where rising waters do more than inundate streets; they wash away livelihoods, hope, and dignity. I remember standing ankle-deep in stagnant water in Khayelitsha, listening to a resident say, “We don’t just fear the floods. We fear being forgotten.”

This statement haunted me. While policy briefs and technical reports praised “smart city” solutions, the communities I worked with were struggling to access even basic drainage. That tension, between technological promise and urban neglect, sparked this inquiry.

I am an urbanist with deep roots in migration, informality, and governance research. But with AI encroaching into planning, I realised I needed to interrogate its implications, not just as a digital tool but as a political actor. Could Artificial Intelligence, I wondered, truly help cities adapt to flooding in ways that are equitable and accountable?

Listening to Voices from the Margins

This paper doesn’t emerge from ivory towers; it’s shaped by years of engagement with those living on the edge of the urban fabric. From Lagos to Jakarta, Dhaka to Maputo, informal settlements house nearly a billion people globally. These spaces, what I call "rough neighbourhoods"—aren’t simply informal; they are systematically excluded, poorly mapped, and left out of most technological interventions.

Through workshops, community dialogues, and participatory mapping projects, I’ve learned that residents often have deep local knowledge of flood patterns, where water will pool first, which structures will collapse, and who will be left behind. Yet these insights rarely inform AI models.

This gap in inclusion is not a side issue, it is the issue.

Theoretical Lenses and Conceptual Innovations

In this work, I argue that AI is not a neutral tool. It is embedded in what I call the flood-tech frontier, a space where climate risk and digital innovation collide. The problem? This frontier is too often technocentric, blind to justice, and driven by metrics rather than meaning.

I introduce a socio-technical systems perspective, which treats AI as a governance actor. This means looking at who designs the algorithms, who has data access, whose needs are prioritised, and who gets excluded. From this emerges a new concept: algorithmic exclusion, a phenomenon where entire communities are left out of AI-driven adaptation efforts because of poor data, weak institutions, or digital inequality.

I also offer a justice-oriented framework for AI governance, arguing that we need not just smart systems, but just systems.

Challenges in the Field

Doing research at this intersection was both intellectually thrilling and emotionally demanding.

One major challenge was the lack of Global South representation in AI studies. Most models are built using data from places like the US, Japan, or Western Europe, then applied wholesale to Nairobi or Dhaka. This not only reduces effectiveness—it reinforces epistemic injustice.

Another difficulty was translating the voices of marginalised communities into academic language without losing their urgency or agency. I found myself constantly asking: how do I honour these stories without appropriating them?

Finally, it was humbling to see how digital divides mirror physical inequalities. Cities with the least flood infrastructure also had the least digital capacity, precisely where AI could help most, yet where it's least effective.

Key Findings

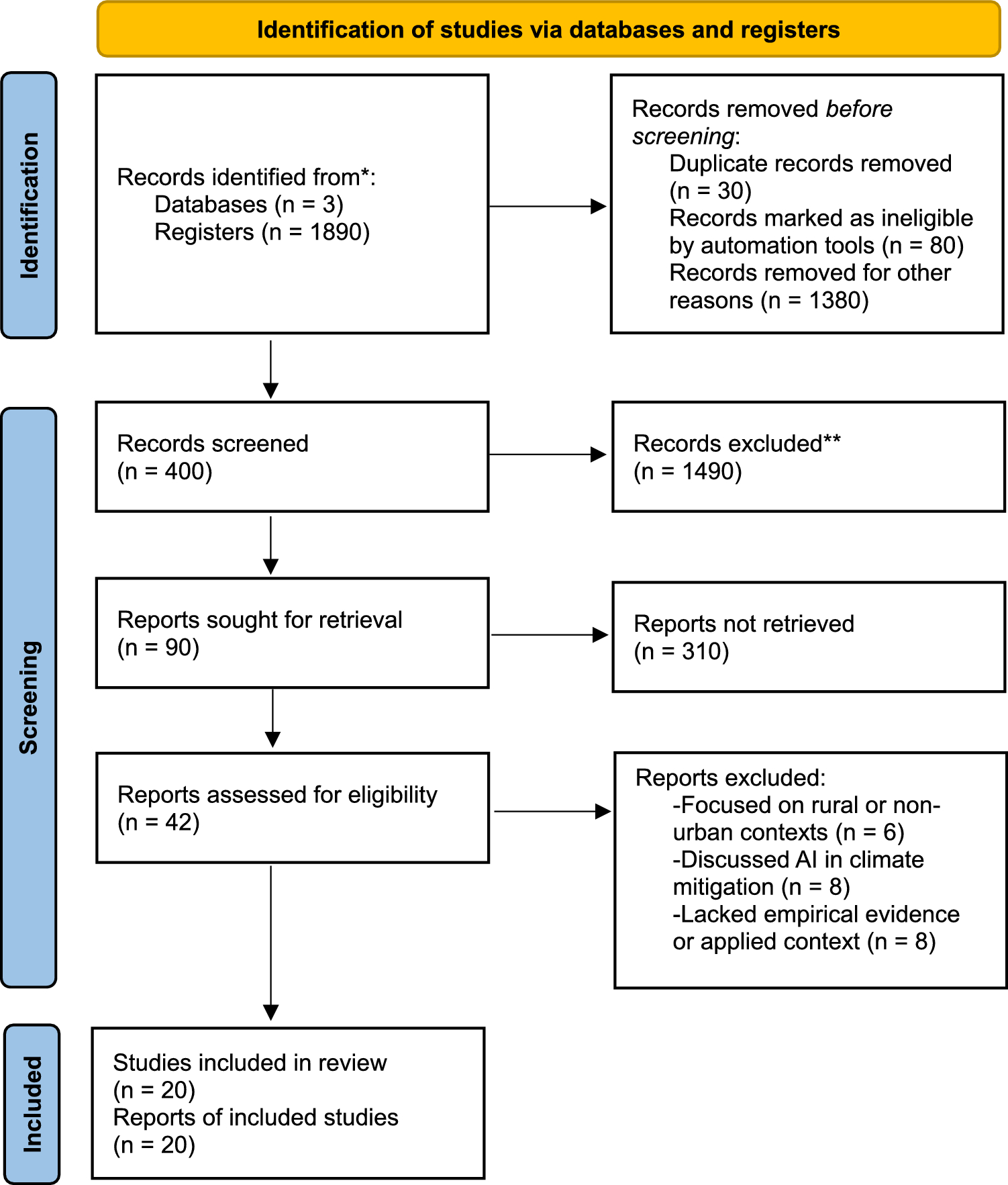

Here’s what the review of 20 peer-reviewed articles between 2014 and 2024 revealed:

- AI can predict floods with impressive accuracy. Machine learning and deep learning models (like neural networks) are powerful tools for early warnings and risk maps.

- But these models work best where data is rich and institutions are strong. That’s rarely the case in informal settlements.

- AI often excludes communities most at risk. This happens due to poor data, lack of local engagement, and opaque decision-making.

- Very few AI tools are designed with community input. Participatory design is missing, and without it, solutions are often irrelevant or misdirected.

- Algorithmic fairness is a real concern. Who decides what counts as risk? Who gets alerted first? Whose needs are prioritised?

In short: AI helps cities respond faster—but not necessarily fairer.

Why It Matters

In a world facing accelerating climate shocks, we cannot afford to widen inequality in the name of innovation. AI offers exciting possibilities, but without ethical frameworks and governance reform, it risks becoming a tool of exclusion.

This study contributes to a growing call to decolonise digital adaptation, ensuring that local knowledge, community agency, and historical justice inform our technological futures.

The findings are particularly urgent for policymakers working on SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). They signal the need for co-produced adaptation strategies, where local voices shape AI deployment from the start.

Reflections and Hopes

I hope readers come away with a deeper appreciation for the complex politics of flood adaptation in the digital age. Technology is not destiny. We must ask: AI for whom? By whom? With what consequences?

Urban planners should rethink how they use digital tools. Policymakers must fund inclusive data ecosystems. Donors should support projects that prioritise community-led innovation. And students? They should be encouraged to ask tough questions, challenge hype, and centre justice in all design.

A Note to Fellow Researchers

If you’re doing work in precarious, data-poor, or highly politicised contexts, take care. Ethical dilemmas are inevitable. Emotional burnout is real. But so is the power of your work to illuminate what’s ignored.

Don’t be seduced by fancy models or flashy metrics. Listen to the ground. Question assumptions. And above all, stay accountable to the people whose stories shape your research.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Global Society

This is an interdisciplinary, international journal that welcomes research on the complexities of modern global society, its development and its challenges.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Business Transformation in the Age of AI and ESG: A Framework for Social Equity, Governance and Sustainability

This Collection explores the profound impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices on business transformation. It focuses on how these evolving forces are reshaping business models while addressing the critical need for social equity, effective governance, and long-term sustainability.

As AI technologies revolutionize industries, they bring opportunities for increased efficiency, innovation, and personalized services. However, they also present ethical challenges, including concerns about data privacy, algorithmic bias, and labor displacement. Simultaneously, the growing focus on ESG standards demands that businesses take responsibility for their environmental and social impacts, ensuring that their operations contribute positively to society and the planet.

This collection aims to highlight how AI and ESG can be integrated to drive business transformation in a way that promotes both technological innovation and social good. It will investigate how companies are adopting AI-driven solutions while adhering to ESG frameworks to foster responsible practices. In particular, it will focus on how businesses can balance profit-driven objectives with the need for credibility, transparency, and sustainability in their operations.

Through a critical examination of emerging trends, case studies, and strategies, this collection will reveal how AI and ESG together create opportunities for businesses to become agents of positive change. It will also highlight the challenges of aligning AI advancements with ethical governance and the social imperative for inclusivity, diversity, and environmental stewardship.

Keywords: Business Transformation, Artificial Intelligence, ESG, Social Equity, Governance, Sustainability, Ethical Business Practices, Technological Innovation, Corporate Responsibility, AI Ethics, Environmental Impact, Social Justice

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jul 02, 2026

Gender, Environment, and Sustainability: Bridging Gaps and Building Future

The pressing challenges of environmental degradation and climate change demand innovative solutions that are sustainable, inclusive, and equitable. Gender, as a critical dimension of social structure, shapes the vulnerabilities, experiences, and responses of communities worldwide facing environmental risks. Women play diverse and pivotal roles as leaders, decision-makers, resource managers, activists, and scientists in addressing ecological issues; yet, they continue to face barriers to access, participation, and recognition within environmental sectors.

This collection, "Gender, Environment, and Sustainability: Bridging Gaps and Building Future," explores the intersection of gender and the environment as a transformative lens for achieving sustainability and social justice. The collection welcomes contributions that examine how gender-based disparities influence environmental outcomes, how women’s empowerment enhances ecological stewardship, and how Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be advanced through gender-inclusive policies and practices. Submissions may cover topics such as gendered impacts of climate change, women’s leadership in environmental governance, gender mainstreaming in sustainability science, and case studies from diverse social, cultural, and geographical contexts.

By bringing together global perspectives, empirical analyses, and practical frameworks, this topical collection aims to foster rigorous research and constructive dialogue on the shared journey toward a more sustainable and equitable future for both genders. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers from diverse backgrounds are invited to contribute their insights and innovations to bridge the gaps and build resilient pathways for future generations.

Keywords:Climate Action, Women’s Empowerment, Gender Equality, Reduced Inequalities, Environmental Sustainability, Quality Education

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Aug 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in