Tiny bubbles that can swim, be seen, and help drugs go deeper

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology and Materials

It’s a familiar challenge in medicine: we may have powerful therapeutic molecules, but getting them to the right place—at the right time, and deep enough into tissue—remains difficult. This is especially true in complex biological environments, where passive diffusion is slow, biological barriers are dense, and clinicians often cannot directly visualize where a drug carrier has gone. Our team (Prof. Wei Gao's group at Caltech) has been interested in a simple question: can we build a microscale delivery system that can actively move, be tracked in real time inside the body, and help drugs go deeper—without complex fabrication?

That question led us to our recent work on enzymatic microbubble robots. At first glance, they look almost too simple: a tiny bubble with a protein shell. But that simplicity is part of the story.

Why microbubbles?

Microbubbles have a unique advantage: they are naturally bright under ultrasound. In the clinic, ultrasound is widely used because it is real-time, portable, relatively low cost. We realized that if we could turn microbubbles into “robots”—adding propulsion and navigation—then we might get a delivery platform that is both actively mobile and clinically trackable.

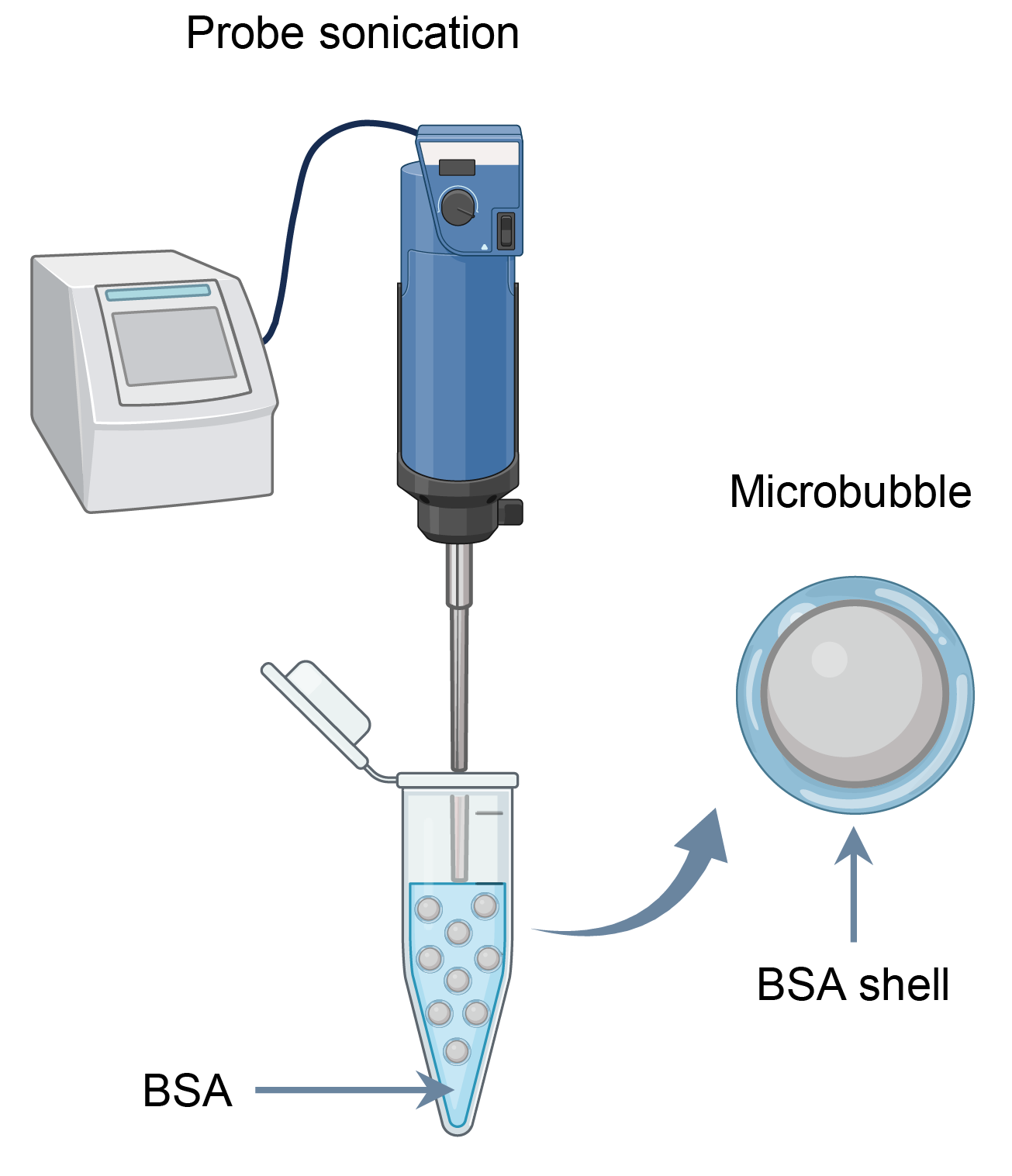

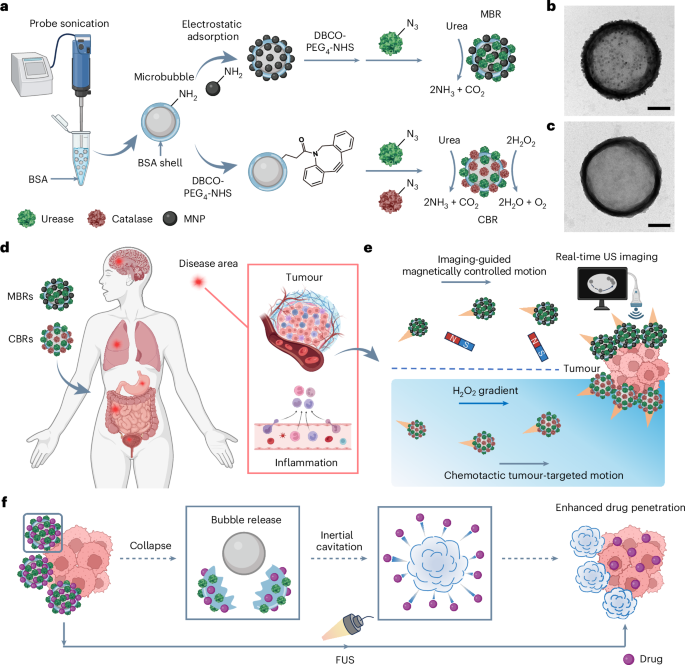

Our robots are built from microbubbles with a bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein shell, produced through a straightforward solution-based process (Figure 1). The protein shell is not just a passive container: it provides abundant chemical handles for functionalization and is inherently biodegradable, both important for biomedical use beyond proof-of-concept studies.

Power with bioavailable fuel

A major bottleneck for many micro/nanorobots is energy: many systems require external fields at all times, or fuels that are not naturally available in the body. We wanted a system that could move using a bioavailable fuel. That is why we functionalized the protein shell with urease, an enzyme that decomposes urea—an abundant metabolite—providing autonomous propulsion. This also makes the approach naturally compatible with urea-rich environments such as the urinary system.

Guiding the robot: remote control and self-navigation

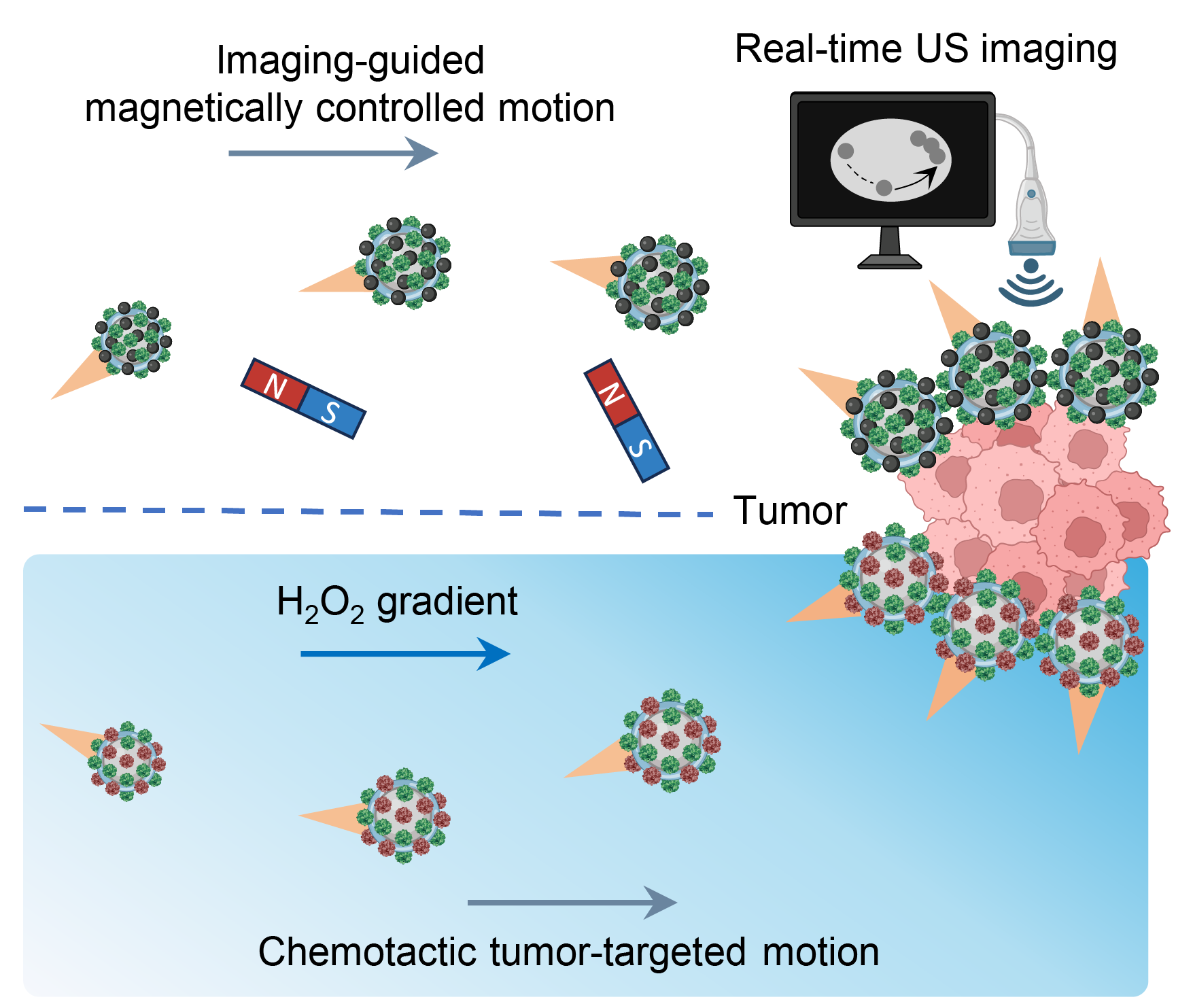

No single navigation method is perfect in vivo. So we built two complementary versions of the robot (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Magnetically controlled motion of MBRs and chemotactic movement of CBRs for tumor targeting

1) Magnetically controlled bubble robots (MBRs)

We integrated magnetic nanoparticles so that the robots could be guided by an external magnetic field while being visualized by ultrasound. This pairing—imaging plus control—is important: it is one thing to move particles, but another to know where they are and whether guidance is working in real time.

2) Chemotactic bubble robots (CBRs)

For autonomous targeting, we functionalized the shell with catalase in addition to urease. Catalase allows the robots to respond to hydrogen peroxide gradients, which are often elevated near tumor sites, enabling a form of chemotactic movement toward diseased tissue.

Designing these two systems side-by-side shaped the project: MBRs represent controllable, operator-guided navigation; CBRs represent self-guided navigation that leverages local biochemical cues.

On-demand ultrasound trigger

A key feature of microbubbles is how strongly they respond to ultrasound. We leveraged this property to turn focused ultrasound (480 kHz) into a simple, on-demand switch: once the robots reached the target, ultrasound activation produced short-lived mechanical effects that enhanced tissue penetration and improved local delivery. Because ultrasound is already widely used in the clinic, we designed the activation to stay within a practical and safe operating range for biomedical applications.

From navigation to therapy

What excited us most was seeing navigation, imaging, and activation work as a single workflow in vivo, rather than as separate features on a slide. In a mouse model of bladder cancer, we tracked robot accumulation with ultrasound and then applied focused ultrasound to trigger activation at the tumor site. This step was more than imaging guidance: it became part of the therapy. With on-demand activation, we saw enhanced local transport and deeper payload penetration, translating into stronger tumor control than non-activated or non-targeted conditions.

Just as importantly, we built the system with translation in mind: it can be prepared in a straightforward solution process, the protein shell is easy to modify, and ultrasound provides a familiar clinical tool for both tracking and activation.

What we hope this enables

Our broader goal is not a single robot, but a versatile platform—one that combines enzyme-powered motion with real-time ultrasound visibility, offers both guided and self-directed navigation, and can be activated on demand to help drugs reach harder-to-access regions.

Looking ahead, we are excited about expanding the concept in several directions: adapting the strategy to other enzymatic engines and disease-relevant gradients, exploring different therapeutic cargos, and continuing to bridge the gap between microscale robotics and clinically established imaging/actuation tools.

This project reminded us that “simple” does not mean “limited.” Sometimes, starting from a familiar clinical material—like a microbubble—and reimagining what it can do is the fastest path toward systems that might one day be useful beyond the lab.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Nanotechnology

An interdisciplinary journal that publishes papers of the highest quality and significance in all areas of nanoscience and nanotechnology.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in