Unlocking Our Ecological History

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Arts & Humanities

As a child, I would stare for hours at dioramas of the first humans. These usually consisted of Africa's grasslands, where sweeping vistas included herds of elephants, zebras, and the odd pride of lions in the distance. This was the Garden of Eden from which we emerged. From here, we gradually spread across the earth, overcoming deserts to tundras in the process. Today, this knowledge is widespread. Except we now know this is probably wrong.

In the last few years there has been a growing realisation that there were multiple stem populations in Africa that contributed to the emergence of our species. The physical features and behaviours that define all living people today did not emerge in a neat package at one place and at one time. Rather they emerged gradually, in a mosaic-like fashion at different times, and at different places around 300 thousand years ago. The problem is, beyond a few small areas of good fossil preservation, we know very little about the remote past in Africa. Did all regions of Africa play some sort of role in the emergence of our species? Within these different regions, did humans only evolve and live within Africa's savannahs and grasslands?

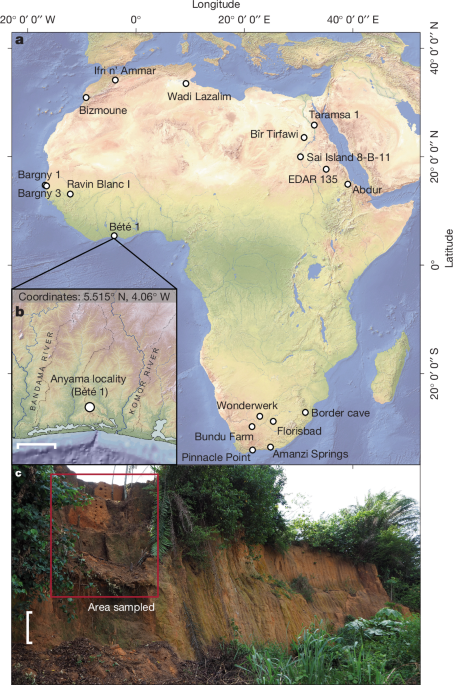

To answer these questions, I set up a major research project across West Africa - one of the least well understood regions of Africa for human evolution. The work of pioneering West African colleagues in particular drew me to Côte d'Ivoire, where the man who would become our co-author had discovered a very intriguing site. Professor Guédé had worked with the now late Professor Liubin in a joint Ivorian-Soviet archaeological mission in the 1980s and early 1990s at a locality by the banks of the Bété River, north of Abidjan. Here, quarrying had uncovered metres and metres of sediment, containing buried stone tool artefacts. The stone tools at the base, in what we refer to as Unit D, seemed to be very ancient. They featured classic Middle Stone Age artefacts, the first and longest lasting material culture stage associated with our species. With these Middle Stone Age artefacts were other, more unusual tools that were very large and robust. Owing to the scientific limitations of the time, Professors Guédé and Liubin were unable to date the human occupation of the site, nor were they able to establish its ecological context. However, their stellar work on the sedimentology and stratigraphy meant that, after a hiatus of of thirty years, the site could be reinvestigated by a new joint Ivorian-German mission. The fact that new climate research indicated that the area of the site had always been a rainforest added a new dimension of possibilities. Would we finally be able to establish an ancient link between our species and this major world biome?

In March 2020, we visited the site. The five weeks of fieldwork were dramatically truncated by the Coronavirus Pandemic. Yet we were able to clean and cut back the original trench to obtain samples within the short time frame available to us. Over the next years, the story unfolded. First, the chronometric age of the site was established using two independent methods of dating, Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dating, and Electron Spin Resonance Dating. The dates overlapped, giving us a most likely age of 150 thousand years . This was a shock, and the oldest known dates from Côte d'Ivoire. We already had enough information to publish something exciting, and yet a hunch kept me from doing so. Instead, we began to investigate the dated sediments associated with the oldest tools. First, we examined the isotopic signature of tiny leaf wax remains found inside them. These chemical signatures are different in open environments to those in closed canopy forests. When the results came through, the data suggested we were looking at a seasonally inundated forest. To try to learn more about this, we also looked at phytolith remains - the small silicified remains of plants whose shapes give clues as to the type of ecosystem we were looking at 150 thousand years ago. Again, they pointed to trees and not grasses. Finally, we looked at the pollen remains which were thankfully well preserved. This study revealed both the presence of keystone rainforest trees like Hunteria and Oil Palms, but also anthers - the pods that contain pollen - indicating a fine, local signal. The lack of grasses also indicated that we were not looking at a narrow strip of Gallery Forest by a river, but rather a deep, dense jungle. For the first time we could ascertain a link between humans and rainforests in Africa, the home of our species. That age was more than double the previous known age estimate for humans in rainforests anywhere else.

This discovery showed that humans have a very deep history of engagement with vastly different ecosystems. We did not originate in one and have to learn how to adapt to others much later on in human history. We were already doing this by the Middle Pleistocene. Not just this, but these first forays into diverse habits were taking place in West Africa, a region once considered to be too far from the main stage of human evolution to be of interest. All of this raises a raft of new questions: how much further back could the record go? What was the impact of human habitation in rainforest ecosystems over time?

We are grateful to our Ivorian collaborators for both setting up and facilitating the results that have been brought forth by a small army of international scientists. The work is a completion of the programme set up by Professor Guédé, and will give the current and future generation of Ivorian and international scientists a lot of food for thought.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature

A weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in