Wellbeing outcomes in partial climate-related relocations

Published in Social Sciences and Sustainability

Climate-related relocation in Fiji

Fiji is at the forefront of climate-related planned relocation, driven by increasing threats from sea-level rise, coastal erosion, storm surges, and flooding. The government has identified approximately 50 communities in need of relocation over the coming decade and has established national policy frameworks, guidelines, and a dedicated relocation trust fund to support this process.

With relocations taking place globally and on all inhabited continents, Fiji’s experience offers valuable lessons for other nations confronting similar climate risks.

A focus on partial climate-related relocations

Research, policy and practice on planned relocation tend to be predicated on the assumption that communities can and will relocate as a full community. Studying partial climate-related relocations is crucial because they are becoming an increasingly common response to climate risks, particularly in contexts where full relocation is not feasible or desired due to financial, logistical or psychosocial reasons. Yet, little has been researched about how those who stay and those who relocate experience the process and their wellbeing outcomes in the short and long term.

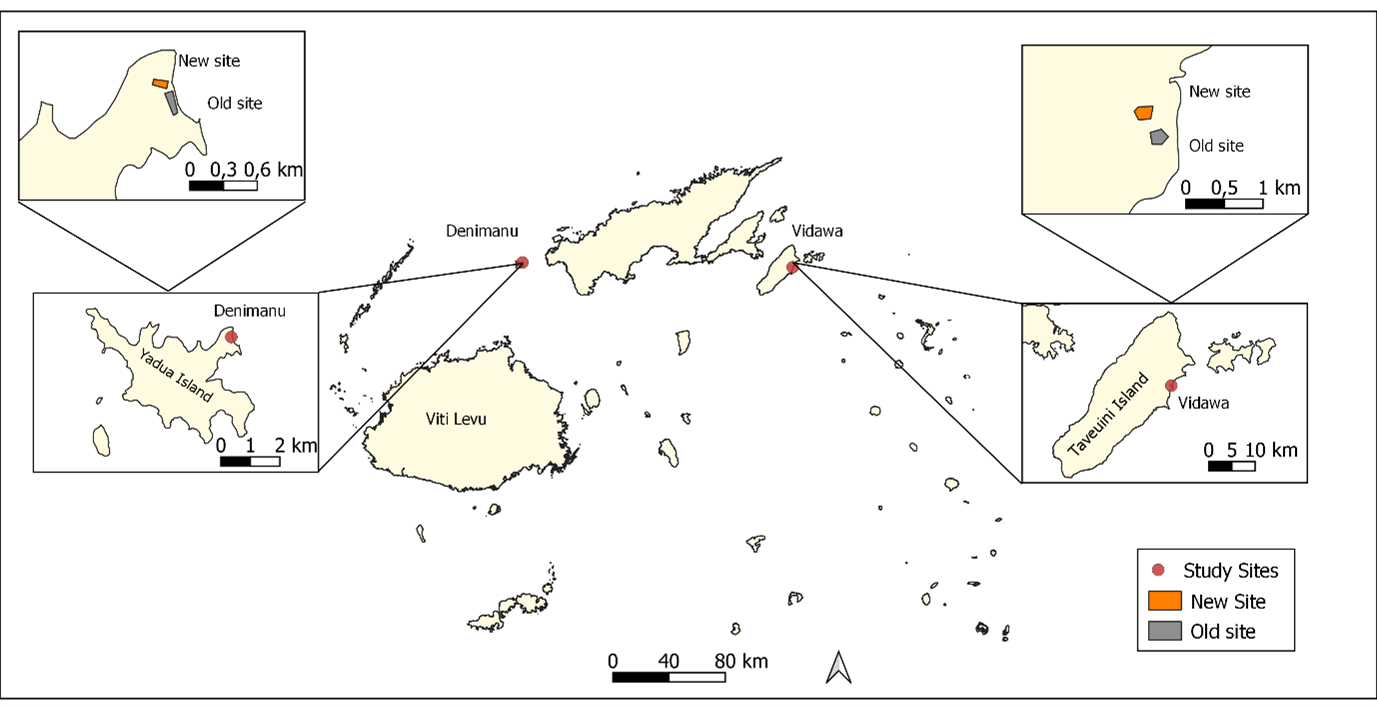

This study focuses on two villages in Fiji where partial relocation has taken place: Vidawa, where residents are currently self-initiating relocation due to ongoing coastal hazards, and Denimanu, where a government-led partial relocation occurred in 2013 following storm surges associated with a cyclone.

The two study sites in Fiji of Vidawa and Denimanu are represented by red dots in addition to the locations of the new sites (orange) and the old sites (grey)

Why we used a well-being lens

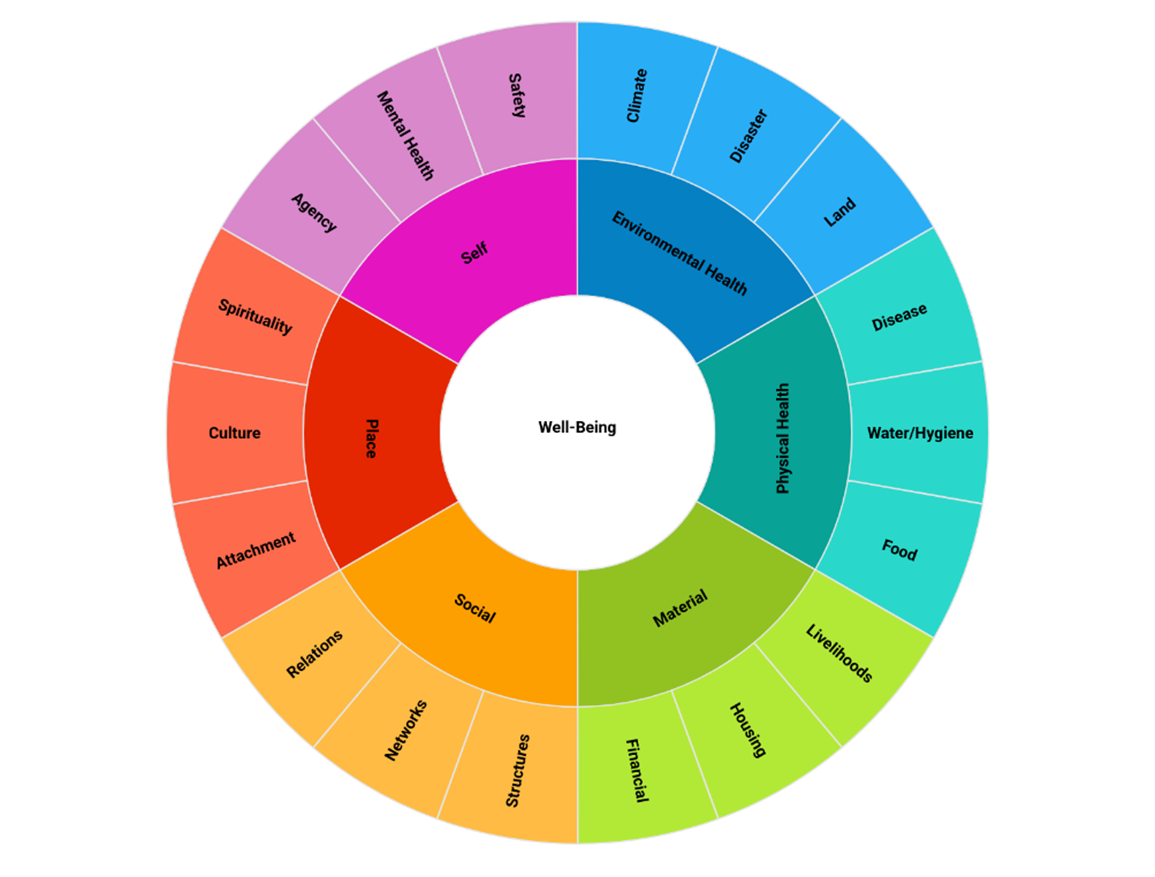

Wellbeing offers a valuable lens for assessing the outcomes of climate-related relocations, particularly partial relocations, which can lead to fragmented communities and diverse impacts on people's lives.

Beyond ensuring physical safety, adaptation efforts must support the broader conditions that enable people to live meaningful and connected lives. This includes material wellbeing (access to essential resources), subjective wellbeing (people’s own perceptions and experiences), and relational wellbeing (social ties and place-based connections). By also considering eudaimonic wellbeing which emphasizes purpose, self-realization, and values-based living, adaptation can move beyond short-term protection to support dignity and agency.

This is especially critical in Indigenous contexts, where place-attachment and community ties are central. Studying wellbeing helps illuminate both the practical and deeply personal impacts of relocation, making it essential for guiding more holistic, just, and appropriate adaptation responses.

Wellbeing framework showing the six themes (social, place, self, environmental health, physical health, and material) and subthemes

Why we used Q-method

We used Q Method in our study. This approach was chosen because it bridges qualitative and quantitative approaches to capture subjective experiences in a structured yet culturally sensitive and accessible way. Q Method allows participants to express their perspectives through ranking statements and then discussing why people ranked statements the way they did. This made it ideal for unpacking the layered, personal, and collective meanings associated with climate-related relocation and, revealing underlying patterns in how people perceive wellbeing and relocation impacts.

In our study we printed off and laminated A1 Q-Grids, as well as 36 statements translated into the local language. We sat down with community members in each village, and asked them to sort the statements based on their own perspectives. This occurred in places identified as preferable for participants including people's homes and communal spaces.

Participant using a Q-grid to rank statements on wellbeing and relocation during fieldwork

What we found

The study revealed that partial relocation shape people’s wellbeing both immediately and years after a partial-relocation, with marked differences between those who relocated and those who stayed.

In Vidawa, where the relocation is community led and underway, relocated residents felt happier and safer, while those left behind were more likely to feel anxious and worried about the future largely because of continued hazard exposure.

In Denimanu, a government-led relocation in 2013, outcomes were more complex, with wellbeing closely tied to perceived and experienced agency in the relocation and cultural continuity. Still, even in Denimanu where the relocation happened over ten years ago, experiences of wellbeing are shaped largely by whether individuals relocated or stayed behind.

These findings matter because they highlight that relocation outcomes are heavily influenced by whether communities relocated or remained emphasizing that adaptation actions taken now will have impacts on people's lives in both the short and long term.

Where to from here

Our findings highlight that wellbeing outcomes are impacted by whether communities remained or relocated in partial-relocation contexts. While some wellbeing outcomes were positive—particularly where communities were actively involved in decision-making—others reveal persistent challenges.

Moving forward, greater emphasis is needed on community-led relocation processes that enhance agency of communities, while recognizing the role that the State and external organizations can play in enabling such efforts. Tailored support is also crucial, as experiences of relocation differ across demographics, including age and ability.

Short-distance relocations may help maintain place attachment, but ongoing attention to intra-community differences, inter-site connectivity, and support for those left behind is essential.

Future research should track evolving wellbeing narratives over time, particularly in relation to policy implementation, and expand to include host communities and relocations across varied distances. Equally important is the need to develop policy frameworks that actively incorporate the lived experiences of affected communities, so that adaptive relocation processes support not only physical safety but also the conditions for living well and sustaining long-term wellbeing.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in