‘You can’t get there from here:’ Birth of a biotech platform

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology

Spirulina is stubborn.

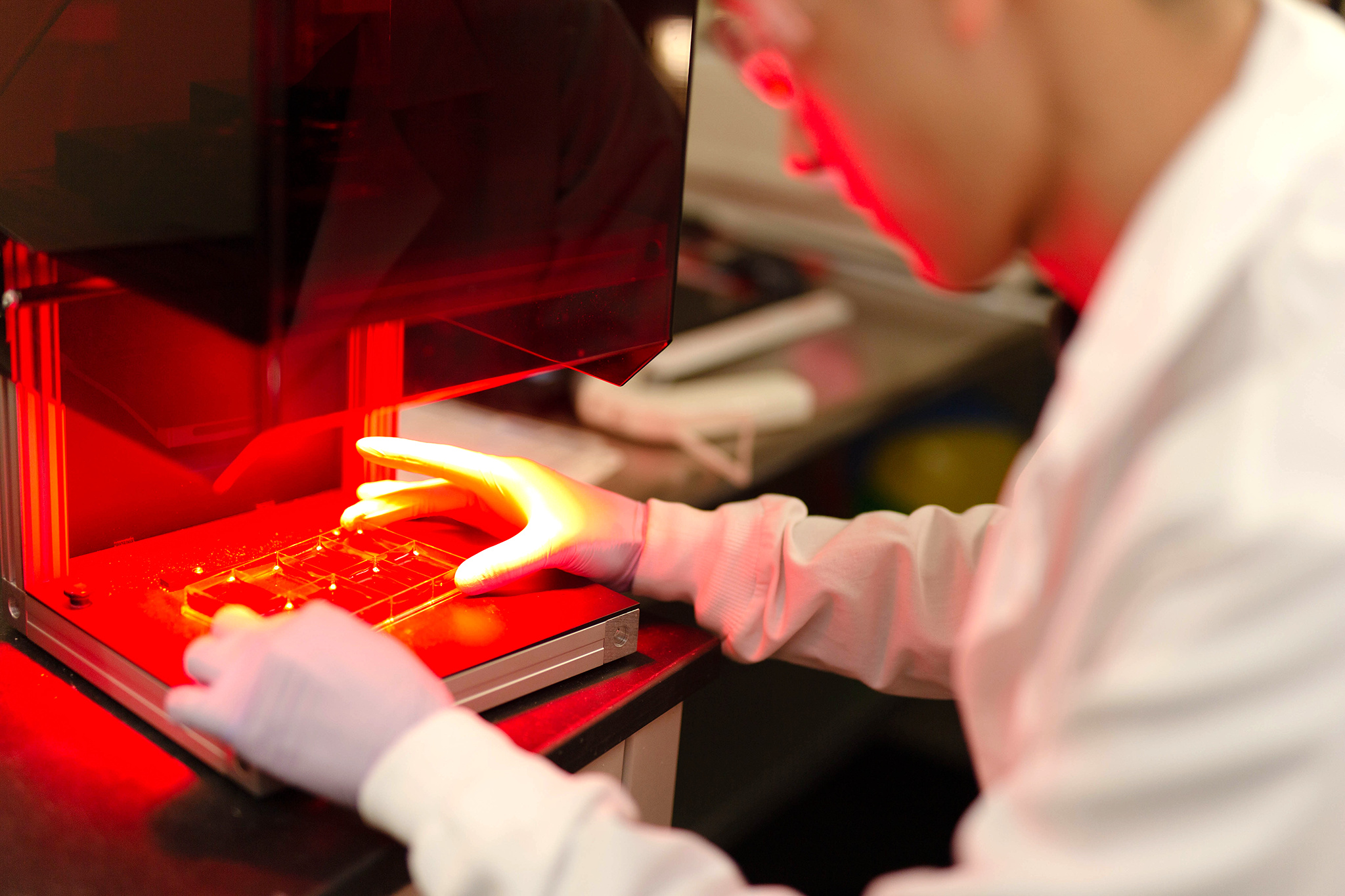

Jim Roberts thought he knew what he was getting into when he ordered a few vials of frozen spirulina culture for the lab. Chock-full of protein and easily grown at vast scale, the blue-green algae made an ideal candidate for a biomanufacturing host: if you could genetically manipulate it, you could turn spirulina into a factory for any number of useful products.

But nobody could. For years, spirulina had defied scientists’ attempts to engineer it.

Roberts wanted to try anyway. His company, Matrix Genetics, had prior success engineering other resistant microbes. More importantly, it needed to find a new direction.

It was 2014. Matrix was founded during the biofuels craze, and the company was engineering microalgae to make fat droplets of oil. Its science was sound. Its commercial footing, less so; the company’s prospects were plummeting alongside the price of crude oil. Roberts turned to spirulina as one possible new direction for the science they’d developed.

Initially, it looked like a dead end. “We learned like everyone else that spirulina was not genetically manipulable with standard laboratory techniques,” Roberts said. “We just couldn’t get any new genes inside.”

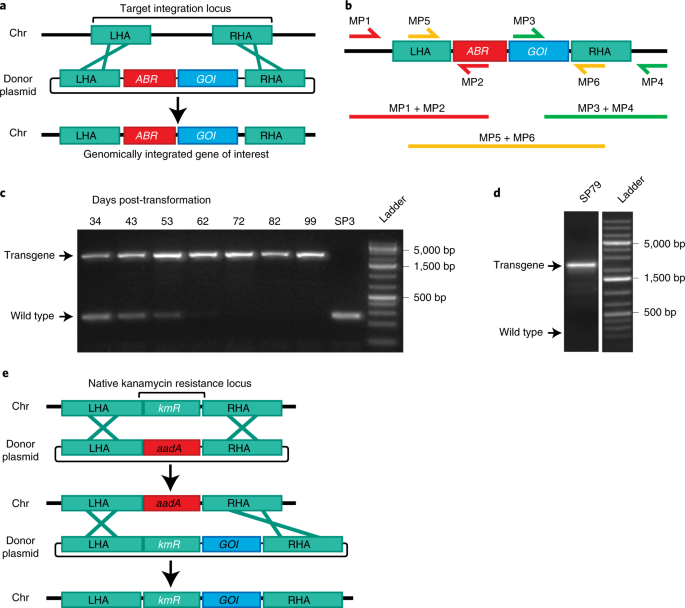

But Matrix had recently developed tools to engineer another type of blue-green algae, so Roberts and his research colleague Ryo Takeuchi took another run at it. They used their new toolkit to try and knock out the gene for one of spirulina’s pilus proteins, which it needs to move around. And there, on an agar plate, was visual proof of success: instead of swarming everywhere as spirulina tends to do, the cells sat immobile in discrete little colonies.

They had discovered the only known methods for engineering spirulina, a breakthrough that formed the foundation of a new company, Lumen Bioscience.

Platform possibilities

Brainstorming for this new company began at a Thai restaurant housed in an old boxcar.

That’s where Roberts regularly bumped into Brian Finrow, a self-described “recovering lawyer” now working in corporate development for a neighboring biotech company. The Thai joint was the only restaurant around and the two typically arrived early to beat the lunch rush, which often gave them the place to themselves.

“He always told me ‘Matrix doesn’t have a commercial bone in its body,’” Roberts said. “And he was right—biofuels didn’t lead anywhere.”

Roberts in turn shared some of the other ideas that were bouncing around inside Matrix, like the collaboration with University of Washington researchers on a malaria vaccine. He also shared stories from his days at Columbia University, where he helped develop technology to engineer mammalian cells—research that made it possible to manufacture monoclonal antibodies at scale, a 100-year-old dream that dramatically changed the treatment of diseases like cancer and arthritis.

But the blockbuster biologic drugs that emerged were pricey. These cellular factories have fussy growth conditions, and convoluted steps are needed to isolate and purify their output. Even after decades of improvement, costs for these drugs are still in the range of $100-$200 per gram. Roberts had a hunch spirulina could produce biologics for a lot less. And since people have consumed it for centuries, spirulina could be an oral delivery vehicle as well as a drug-making factory.

Lumen's short-lived

spirulina extract product.

Biologics was a big category, though—maybe too big. Where to start? Roberts and Finrow, now Lumen’s newly minted CEO, hashed out an initial business plan: make “spirulina extract,” a vibrant blue food colorant used as an alternative to petroleum-derived artificial colors. This would provide an immediate revenue stream that could support development of more valuable products like biologic drugs. Demand was high for the natural blue pigment, and Lumen raised substantial financial backing on the promise of a purer, more stable variety.

And then that business plan blew up.

Pivoting

Shortly after Lumen’s founding, the market price for spirulina extract began a slow but steady decline. Subsidized overseas production had upended the market, dragging prices down in its wake.

It was potentially catastrophic, but serendipity intervened. Unbeknownst to Lumen, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was wrapping up an 18-month global search for a solution to a particularly thorny problem. A problem that Lumen just happened to be ideally positioned to help try and solve: the stubbornly high infant mortality rate caused by diarrheal diseases in the developing world.

With conventional approaches having failed, the Gates Foundation wanted to try something unconventional: orally delivered antibodies. Their idea took its cue from Mother Nature. All mammals secrete antibodies into breast milk to neutralize pathogenic viruses and bacteria in an infant’s GI tract before they can cause illness.

But pulling this off would mean making antibodies far cheaper and in far greater quantities than anyone had seriously attempted before. And that seemed unlikely to happen with mammalian cell technologies; after decades of advances, they could only get so much cheaper.

“It’s like the old New England joke,” Finrow said. “You can’t get there from here.”

But Lumen’s platform was different. Maybe it could get there.

Llama-inspired focus

There was just one snag. Spirulina lacks certain molecular machinery essential for making exact copies of the types of antibodies that circulate in humans.

Fortunately, the Gates Foundation had already found a ready-made solution: camelid antibodies. These immune proteins, which occur naturally in llamas, camels, and related animals, are smaller and simpler than typical antibodies but still bind their pathogen targets with exquisite specificity. Even better, the business end of these molecules—the antigen-binding fragment, or VHH—was easy to engineer with the modern protein engineering tools that were just becoming available.

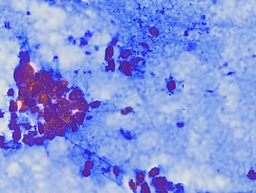

Lumen had found its new focus. The Gates Foundation funded a grant to use spirulina to manufacture and deliver a VHH targeting Campylobacter jejuni, the enteric bacterium at the top of its priority list. Early experiments were immediately encouraging; spirulina could stably produce VHHs in quantities far greater than what had been reported previously in other food-based expression systems, and oral delivery of these VHHs proved effective at preventing campylobacter infection of mice.

Ben Jester, senior scientist at Lumen and the paper’s first author, was part of a wave of hires to build on that work. He remembers walking in for his interview and the office was still under construction. He walked out inspired. “The prospect of working with a new organism that could be used to develop novel therapeutics was really appealing,” he said. “As far as I knew, there weren’t any other companies trying to do that in something other than E. coli or yeast or any other well-worn model organisms.”

And it would truly take a company to do that. The challenge of producing a new drug to FDA standards is daunting, Jester said. He points to the author list on Lumen’s paper as what is needed to get from scientific breakthrough to a product that could save a life.

“Collaborations in academia can be short-lived, but this paper has 45 authors, and most remain involved to this day,” Jester said. “We have so many people working toward a common goal it’s been a continuous collaboration, which is deeply satisfying. I hope people outside Lumen read this paper and come to us and say ‘hey, we have this great protein we’d like to deliver orally. Let’ see if it works on your platform.’ Because really, we’ve only touched the tip of the iceberg of what we can do with spirulina.”

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biotechnology

A monthly journal covering the science and business of biotechnology, with new concepts in technology/methodology of relevance to the biological, biomedical, agricultural and environmental sciences.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in