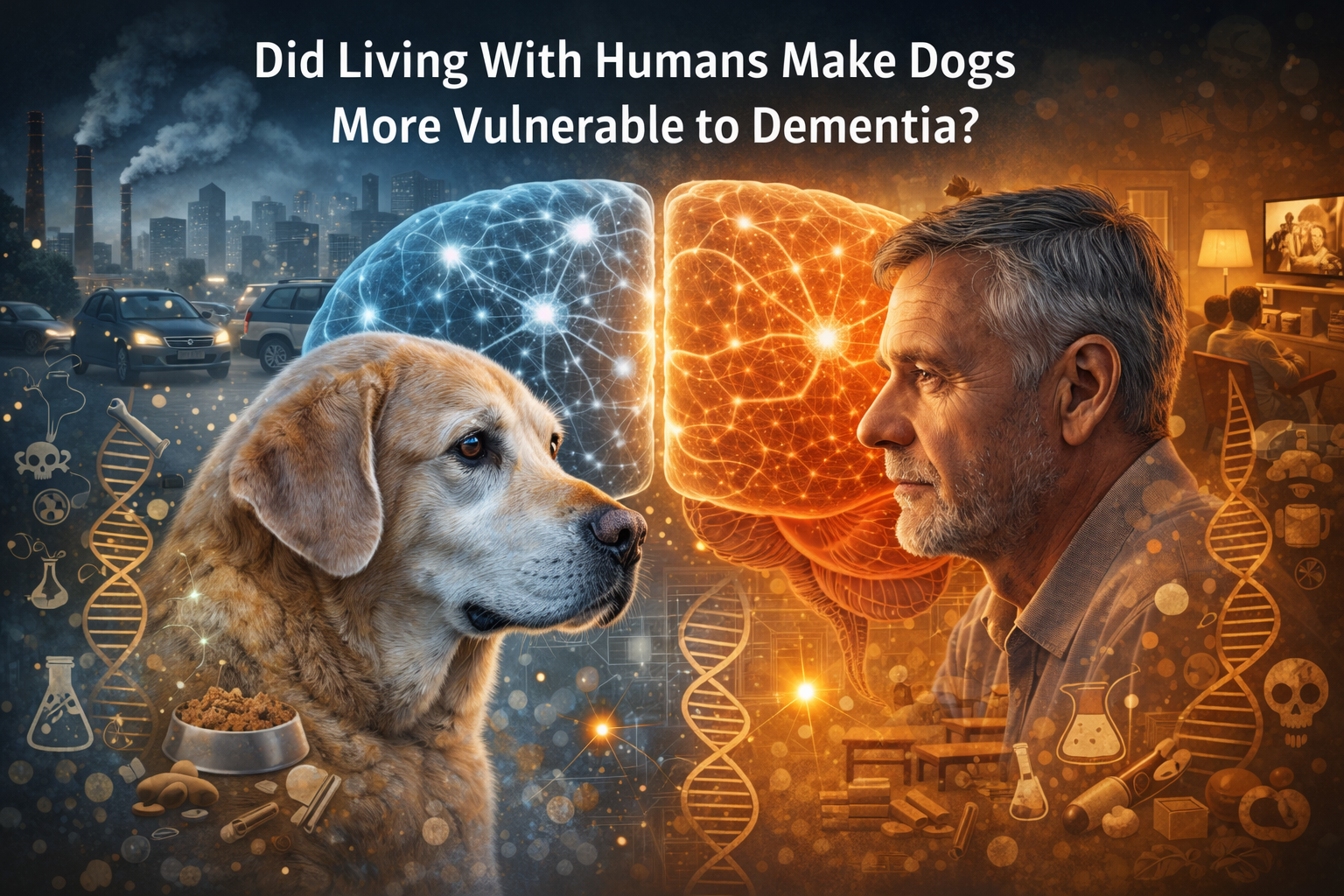

Did Domestication Reshape the Aging Brain? What Dogs—and Wolves—May Reveal About Alzheimer’s Vulnerability

Published in Biomedical Research

For thousands of years, dogs have shared our homes, routines, and environments. No other domesticated species has developed such an intimate biological and social bond with humans. Dogs breathe the same air, consume comparable diets, and are exposed to many of the same environmental pollutants, household chemicals, and lifestyle-related stressors. Over time, this coexistence has produced striking parallels between our species—not only socially, but genetically and pathologically.

Among these parallels is canine cognitive dysfunction (CCD), a spontaneous neurodegenerative syndrome observed in aging dogs. CCD shares clinical features and mechanistic hallmarks with human Alzheimer’s disease. Affected dogs may show disorientation, altered sleep–wake cycles, reduced social interaction, and memory impairment. At the biological level, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and other aging-related processes appear central—much as they do in Alzheimer’s disease.

Because of these similarities, CCD is widely regarded as a valuable natural model of age-related neurodegeneration. Yet while much attention has focused on what dogs can teach us about human Alzheimer’s disease, a more fundamental evolutionary question emerged during our work:

Could domestication itself have altered the dog’s susceptibility to age-related cognitive decline?

How the idea emerged

The idea did not begin with wolves. It began with a simple observation. Dogs and humans not only share emotional lives—they increasingly share chronic diseases. As research on CCD expanded, the parallels with Alzheimer’s disease became more compelling. At the same time, a deeper question surfaced: if dogs now resemble humans in their neurodegenerative vulnerabilities, what about the species they once were?

The gray wolf, the dog’s direct ancestor, lives under profoundly different evolutionary pressures. Wolves are not shaped by artificial selection for companionship, nor do they typically experience the same dietary patterns, indoor lifestyles, or environmental exposures as modern dogs. Comparing dogs and wolves began to look less like a zoological curiosity and more like a natural experiment in how domestication might reshape brain aging.

Turning to the dog’s ancestor

Information about neuropathology in aging wolves is surprisingly scarce. While CCD has been increasingly characterized in domestic dogs, systematic data on cognitive aging in wolves remain limited.

In our recent study, published in Open Veterinary Journal (2025), we adopted a database-driven analytical approach rather than direct neuropathological comparison. Given the limited availability of brain tissue data from aged wolves, we focused on shared risk factors known to contribute to both Alzheimer’s disease and CCD: aging, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, sleep disturbances, and periodontal disease.

We evaluated how these risk factors manifest in domestic dogs compared with gray wolves maintained in captive or semi-captive conditions. Even when environmental variability was partially reduced, domestic dogs showed a greater burden of biological and lifestyle-related factors associated with cognitive dysfunction.

These findings do not suggest that wolves are immune to cognitive decline. Rather, they raise the possibility that domestication—and the genetic and environmental transformations it entails—may have shifted vulnerability trajectories in dogs.

Domestication and neural trade-offs

Domestication is far more than a change in appearance. It involves deep genomic and phenotypic modifications that distinguish domestic populations from their wild ancestors. Across species, domestication has been associated with substantial genomic reshaping, often accompanied by an increased load of potentially deleterious alleles compared with wild relatives.

In dogs, artificial selection strongly targeted genes expressed in the brain, favoring behavioral traits that facilitate coexistence with humans. Many genes influenced during domestication are conserved across species and overlap with genes implicated in human neuropsychiatric conditions. Adaptation to human social environments may therefore have required neural modifications that, while advantageous in domestic settings, could carry biological trade-offs across the lifespan.

Lifestyle changes are equally profound. Domestic dogs inhabit indoor spaces, experience altered activity and sleep patterns, consume processed diets, and are exposed to pollutants, pesticides, heavy metals, and other environmental toxicants. They also frequently live far longer than their wild ancestors would under natural conditions.

From this perspective, domestication may represent a form of evolutionary mismatch—a shift in selection pressures and environmental exposures that reshapes susceptibility to age-related disease.

A shared environment, a shared vulnerability

Dogs and humans share a remarkable predisposition to numerous analogous diseases, including age-related disorders affecting the brain, kidneys, and cardiovascular system. Comparative genomic studies demonstrate substantial overlap in orthologous genes implicated in similar pathologies.

This shared biology, combined with shared environments, gives dogs particular translational relevance. They serve not only as models of disease, but as sentinels reflecting the biological consequences of modern living.

Age-related cognitive decline occurs in both species as part of normal aging. In a subset of individuals, this decline progresses to pathological dementia-like syndromes. Despite decades of research, effective disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease remain limited, partly because its underlying biology remains incompletely understood.

Examining cognitive aging in domestic dogs in comparison with wolves may therefore offer a broader evolutionary perspective. If domestication increased exposure to mechanisms such as oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and lifestyle-related metabolic alterations, the dog–wolf comparison could help clarify how environmental transformation interacts with biological vulnerability.

Importantly, our work proposes a conceptual framework rather than definitive causal conclusions. Direct neuropathological studies in aged wolves remain scarce, and further empirical investigation is essential.

Yet the hypothesis is testable: if domestication contributed to the development or amplification of CCD, then wolves—even in managed environments—might show relative protection from some associated risk factors.

By comparing domestic dogs and wolves, we begin to explore a broader question: how do rapid environmental changes reshape the aging brain?

The answer may lie not only in laboratories and clinical trials, but in the shared evolutionary journey that began when wolves first approached human settlements—and in the environments we have built together ever since.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Open Veterinary Journal 15 (12): 6126-6145 (2025).