Probiotics, microbiota and human health: Sifting hope from hype

Published in Microbiology

“…The Minister also announced the National Microbe for India which was selected by children who had visited the Science Express Biodiversity Special, a train which has been visiting various stations across the country. Voting for the National Microbe took place in these stations and the children have selected the Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) to be the National Microbe for India.” –The Press Information Bureau, Government of India (2012)

In 2012, India became the first nation in the world to designate a National Microbe, and still remains the only nation with one. After its discovery in 1905 in yogurt samples by the Bulgarian doctor Stamen Grigorov, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus became famous as Ilya Metchnikoff’s “Bulgur bacillus.” Metchnikoff’s (incorrect) theory of ‘intestinal auto-intoxication’ held that consumption of harmless lactic acid bacteria lowered the pH of the gut, inhibiting the growth of “proteolytic bacteria” such as Clostridia that produce indoles, phenols and ammonia by degrading proteins. Metchnikoff speculated that the longevity of rural groups in the Russian steppes and Europe that consumed fermented milk was due to the prevention of “intestinal auto-intoxication.” Incorrect and unsupported by evidence though it was, this theory sparked the search for beneficial microorganisms that could be consumed for better health. Today, there are many probiotic products on the market that claim benefits for regular consumers. However, it must be noted that the mere presence of ‘beneficial organisms’ in a food does not qualify it as a “probiotic.” The World Health Organization defines a probiotic in as “Live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host.”

The tenth India Probiotic Symposium was jointly organized by the Gut Microbiota and Probiotic Science Foundation (India), the Institute of Home Economics, New Delhi (a college within the University of Delhi system) and the Pushpawati Singhania Hospital and Research Institute, New Delhi. Thus, it brought together, in an organizational sense, academia and healthcare providers.

However, we must point out that the symposium was pleasantly more inclusive than might be expected of a scientific society focused on probiotics. A glance at the scientific programme will indicate the “eubiosis1” if you will, of researchers from both clinical and academic research backgrounds. It featured many oral and poster presentations by researchers who work on the human microbiota, and not just the gut microbiota. The detailing of experimental methods by the presenters was especially helpful for the listeners to understand the scope of the results presented, as well as learn about the instrumentation and experimental approaches available to conduct research in this field.

The carefully chosen and curated poster presentations by active researchers (doctoral students and post-docs) provided a behind-the-scenes view of the actual process and, more importantly, the uncertainties and caveats of the research enterprise. It provided participants with the opportunity to critically evaluate research on probiotics and their health effects by placing them within the overall context of the role of the human microbiota in health and disease. The poster session was an opportunity for much debate, discussion, and lest we forget, forging new collaborations. Presenters of the three posters adjudged the best among those on view were duly recognized with Young Investigator Awards.

A highlight of the oral sessions was the last item on the program – a moderated panel discussion on various aspects of probiotics in human health. This led to many interesting and thought-provoking perspectives on the issue that provided the audience with a more holistic view than could be obtained from a purely didactic session focused on a single topic. In my opinion, another major and lasting benefit of attending this symposium was the compilation of detailed and comprehensive reviews written by expert practitioners and researchers on various aspects of probiotics that was given to all participants (“Probiotics in Health – Emerging opportunities”). For those with interest in pursuing research in this field, or just curious to increase their understanding and knowledge, I would like to highlight links to the peer-reviewed literature on probiotics and gut microbiota collected by the Gut Microbiota and Probiotic Science Foundation (India). Indeed, the compilation and dissemination of scientific information related to this field is probably the most underappreciated service of the Foundation.

Notes:

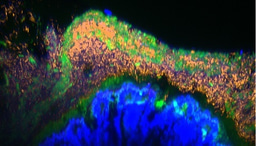

Poster image from Fig. 3 (A) in Kang et al. (2019)2 under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY)

References:

1. Iebba, V. et al. Eubiosis and dysbiosis: the two sides of the microbiota. New Microbiol.39, 1–12 (2016).

2. Kang et al. Inhibition of nitric oxide production, oxidative stress prevention, and probiotic activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from the human vagina and fermented food. Microorganisms 7, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7040109 (2019)

Disclaimer: The above post is not medical advice. No guarantee is expressed or implied regarding the veracity and medical utility of the information provided on external websites and sources. The opinions expressed herein do not represent the views of the TERI School of Advanced Studies or TERI or the symposium organizers. The author declares that he has no conflict of interest with any of the organizers of the symposium.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Very good report Dr Ramakrishnan