The geometry of social avoidance: navigating social interactions

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Have you ever said you’re "growing distant" from a friend, "getting closer" to a partner, or "climbing the ladder" at work? We frequently use spatial metaphors to describe our social relationships–but what if they’re more than just metaphors? What if our brain maps our social worlds like it maps our physical worlds? Could social difficulties be understood in terms of navigational strategies?

That's the core idea we explore in our recent paper published in Communications Psychology. Previous research suggests the same brain systems we use for spatial navigation–like finding our way around a city–also help us navigate abstract social situations. Given that people with high social avoidance often feel unaffiliated and powerless in their social interactions, we asked: is social avoidance related to how people navigate an abstract social space of “affiliation” (like warmth and friendliness) and “power” (like dominance and control)?

To test this, rather than just asking people how they feel, we observed people’s behavior directly in a text-based “choose-your-own-adventure” style game. Imagine you've just arrived in a new town, friendless, jobless, and without a place to live. To meet these challenges, you have to interact with the locals (various characters we designed), and make choices in naturalistic social situations. Nearly 800 people in two different samples played this game online, making choices like: do you share personal info with that chatty co-worker? Do you say yes to your demanding boss's request?

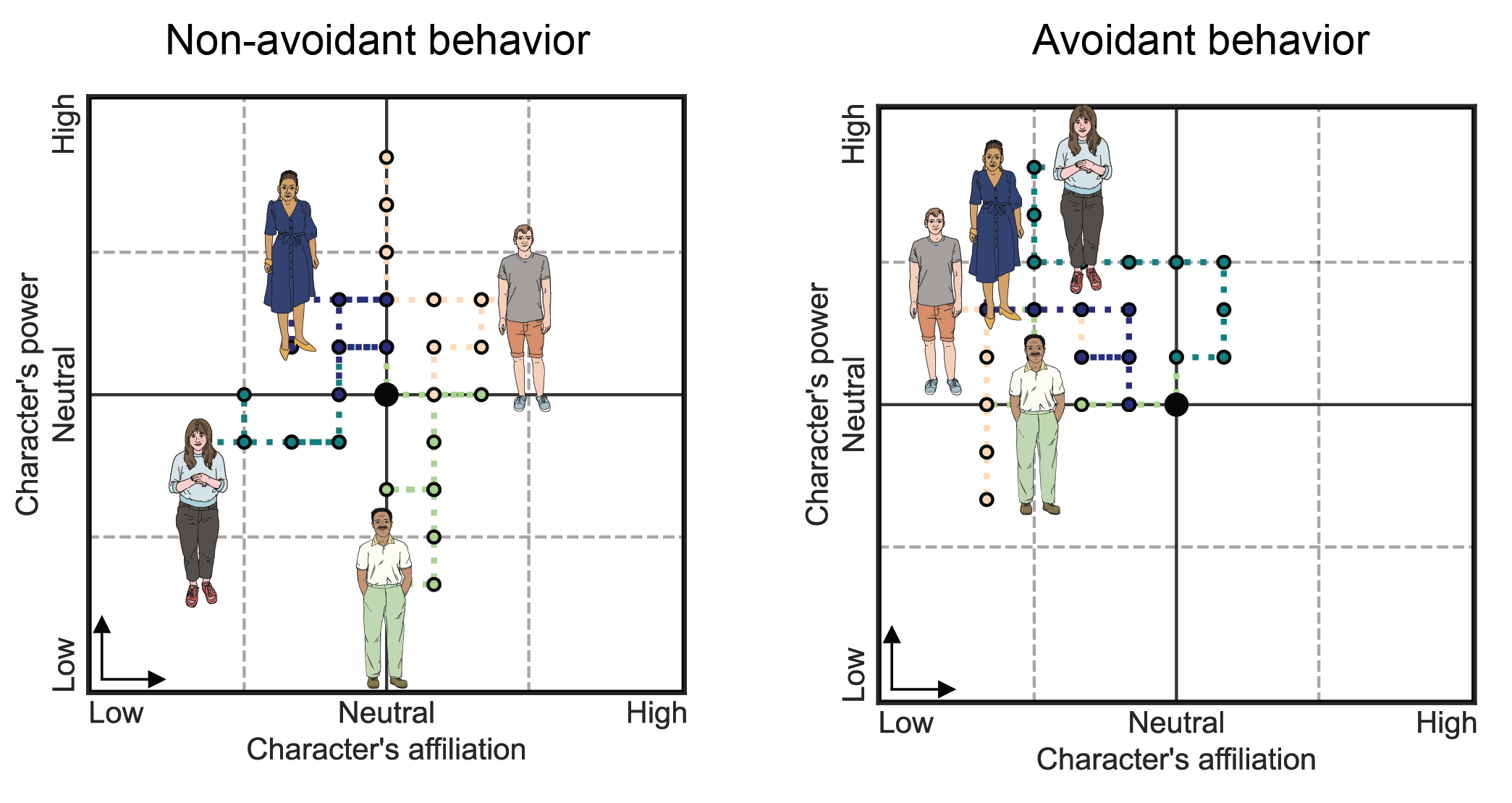

Behind the scenes, each choice the participants made altered their relationship with a character along hidden affiliation and power axes. For example, declining to share info reduced affiliation; complying with the unreasonable demand decreased the participant's power. By averaging the affiliation and power choices within each relationship, we mapped the characters as locations in affiliation and power space. After completing the game, participants filled out standard questionnaires about their real-world feelings and behaviors, including social avoidance symptoms, and then we compared these self-reports to the character locations.

We found a clear pattern: people who reported higher social avoidance in questionnaires made choices that placed them in positions of low affiliation and low power relative to the characters. Social avoidance wasn't just about being less friendly or being more submissive; it was a behavioral pattern combining the two. This effect was present in two large, separate groups of participants, and was specific to social avoidance, rather than mood or compulsivity. Importantly, people who showed this behavioral pattern also wrote more negatively about the game's characters afterward, linking this interaction style to negative subjective perceptions of the characters.

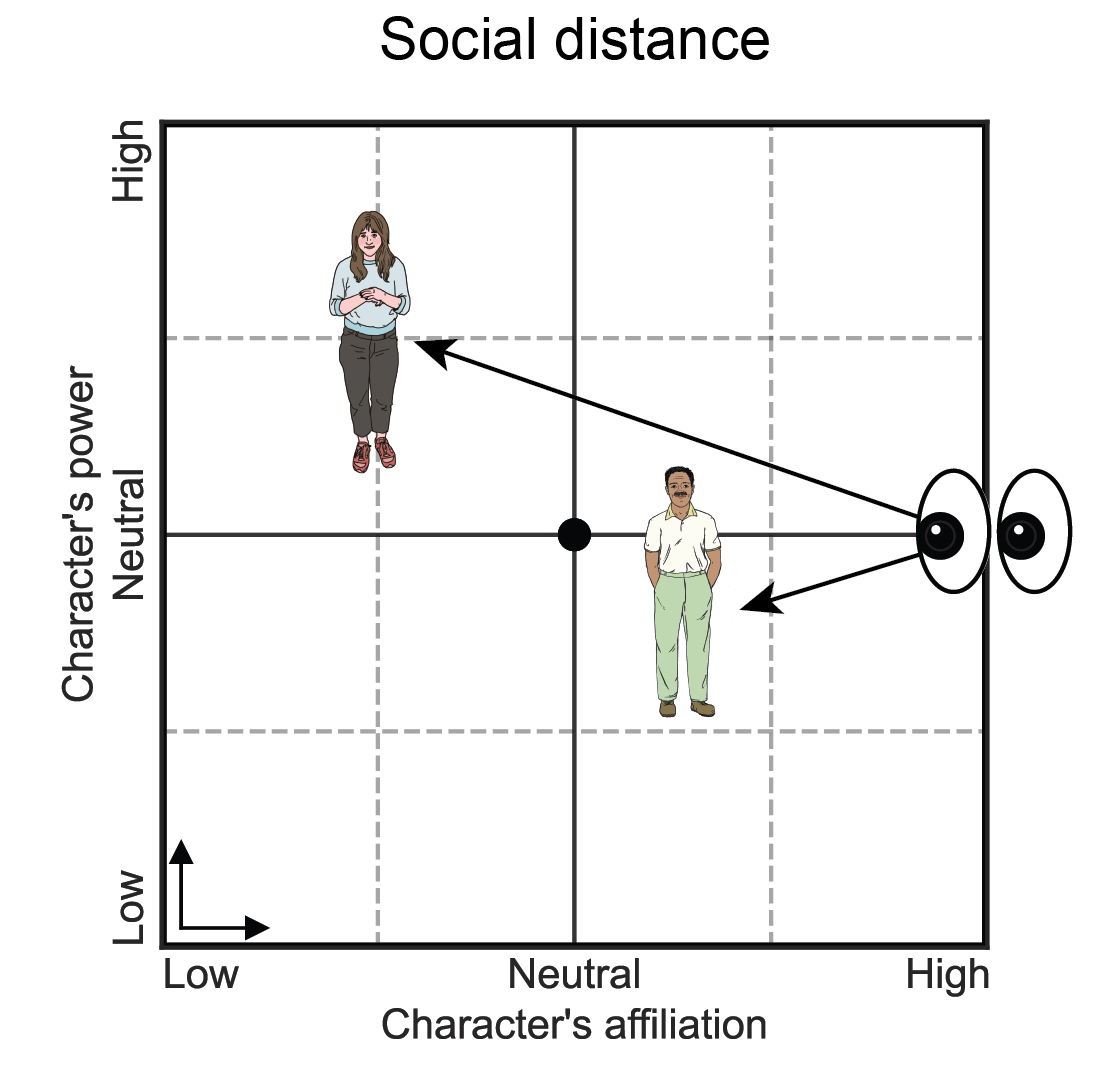

To capture how socially close the participant kept the characters, we calculated a “social distance” metric, derived from each character’s affiliation and power locations. Participants who maintained greater distances in the game also reported smaller and less varied social networks in real life, suggesting our game, and its simple geometric measures, tapped into genuine social tendencies. Social avoidance isn't just a feeling; it’s a measurable way of navigating the social world that keeps people at a distance.

Moving forward, we plan to study clinical disorders, such as Social Anxiety Disorder. Our previous research suggests that the brain regions responsible for spatial navigation also track the changing relationships in this game; adding brain imaging to these measures will let us study the neural basis of social connection and avoidance. We also plan to make the game more immersive, for example by using artificial intelligence for more adaptive characters and interactions. Particularly exciting is the possibility of using these tools to track how someone's social interaction style changes over the course of therapy. By understanding social avoidance as a navigational strategy, we hope to find new ways to help people chart a different course in their social lives.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in