kaKAkaKAkaKAkaKAkaKAkaKA

This piercing series of staccato notes is usually attached to a male Bar-tailed Godwit, showing off for a rival or prospective mate on the Alaskan tundra. But the breeding season will not start for nearly two months, and the call is coming from a bird at the Manawatu River estuary in New Zealand, more than 11,000 km straight-line distance from the closest nesting site. Here, this call has a different meaning. Some combined influence of date (6 March), time of day (just after 6 pm), and wind (~30 kph, edging toward southeast) has at least one godwit thinking about flying north, and voicing this thought to anyone within hearing. Pivoting my spotting scope toward the intermittent call, I eventually discover the caller. It is 4YYRB, and I stop wondering why I have come all this way.

In fact, I had still been questioning the sanity of flying across the globe, from The Netherlands, to witness the events of today. When I embarked, in late February 2020, scattered cases of COVID-19 were being reported from an ever-widening geographic area, and things were surely worsening. There were still no cases near my home, nor in New Zealand at all, but there was every sign that travel restrictions and border closures were on the horizon, given the current trajectory of what people were starting to call a pandemic. Wise council, including several of the voices in my head, advised me to cancel the trip. But could I give up on the 13th year of a long-term dataset so easily, over something that might not happen? Anyway, there were worse places than New Zealand to get stranded indefinitely. I went for it. And I certainly don’t regret it.

A large but modestly colored male godwit, 4YYRB joins two other males of similar description at a puddle on the mudflat, popular with the locals for pre-departure baths. And there is no doubt about their intentions – the frantic bathing and thorough preening, interspersed with shorter two-note calls (Ka ka), inviting others to join the proceedings. These godwits will depart on migration in the next hour or two.

By 18:35, the trio seems to have enlisted two large, pale females to their cause. After a brief crescendo in chatter, the small group suddenly takes off toward the northwest, and I lose them briefly in the sun. As my eyes adjust, they come flying back, high overhead, now trailing three or four other hesitant recruits, before settling again on the mudflat, well away from the main flock of about 150 godwits that are moving with the rising water toward the main high-tide roost. Someone wasn’t quite ready to go. They settle back into enthusiastic preening, calling, and last-chance foraging. This ritual continues as the sun sets at 19:48. Finally, at 20:06, the group takes off again, rises slowly over the mudflat and then the adjacent beach dunes, and disappears from sight to the northwest over the Tasman Sea. These eight birds, including 4YYRB and two other familiar individuals (males 6RBWY and 6WBWW), will not land again until they reach the Yellow Sea region of Asia, about 10,000 km and 7–8 days from here. The estuary falls quiet again.

4YYRB gets his name from the individually recognizable assortment of colored plastic that adorns his legs. He has two yellow bands on his lower left leg (YY), a red band above a blue band on his lower right leg (RB), and a white ‘flag’ (a white band with a prominent extension, internationally translated as ‘banded in New Zealand’) placed above the right-leg bands (i.e. in position 4, of eight possible placements relative to the other bands). This marking system has been used in New Zealand since 2004, with the intention of discovering exactly where godwits (and other shorebird species) go when they migrate away from these shores. This has been spectacularly successful, due to the predilection of people along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway to aim their binoculars, scopes, and cameras at shorebird flocks, and then to seek out information about the curious color-band combinations they detect. Since he was captured and banded here at the Manawatu estuary in February 2006, 4YYRB has been reported by observers close to 250 times. He has been seen on northward migration in China (March–April 2010 at the Yalu Jiang National Nature Reserve), in southwest Alaska (August 2006 on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, where post-breeding godwits gather to fatten for the trans-Pacific flight back to New Zealand), and on a rare, off-course southbound stop in eastern Australia (October 2012). No fancy tracking technology required, just people looking at birds with half-decent optics.

Admittedly, more than 95% of those reports were made by me, here at the Manawatu, where I have worked, somewhat obsessively, since December 2007. In 2006 (about the time I was looking for a prospective PhD project), Phil Battley at Massey University had made an important realization: most godwit banding had occurred at sites where very large flocks gather in the thousands, which naturally increases the chance of a successful capture. But there was great research potential at a very small site, where particular individual birds could be reliably and repeatedly encountered and captured. We had the big picture on godwit migration, and it was time for more intimate insights. Thus, 4YYRB was among the first 63 godwits individually marked in 2006–2007 at the Manawatu estuary, out of a total local population of about 250. He was already an adult (≥3 years old) upon first capture in 2006, making him at least 17 years old in March 2020, as I watched him depart on migration.

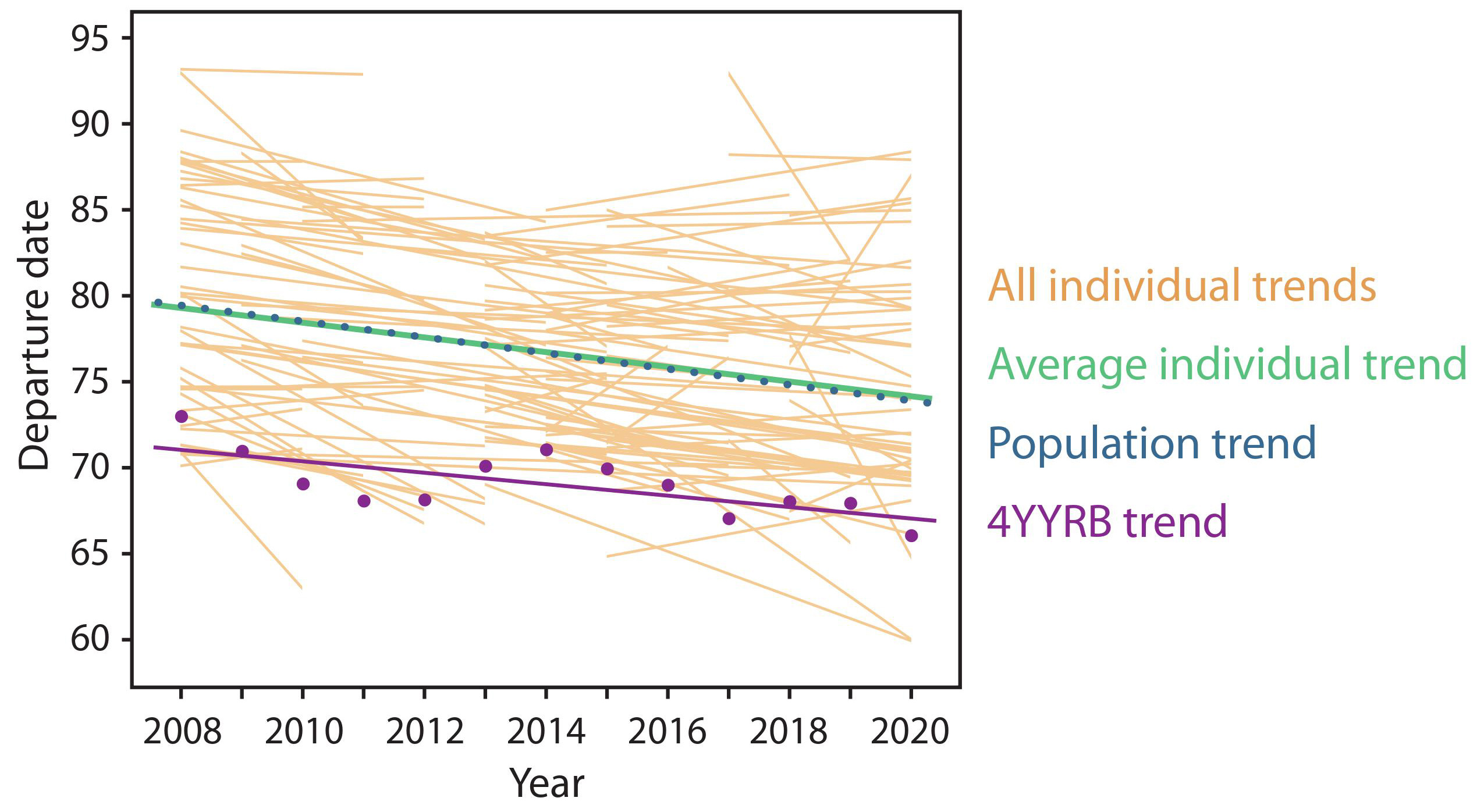

In fact, I have personally witnessed, and in most cases photographed (however blurry), his every departure from New Zealand since I arrived in 2007 to start that PhD project. Godwits depart New Zealand across a 4-week period in March–early April, and 4YYRB is always in the first 25% of individuals to leave the Manawatu. As we learned early on, relatively early departures during this window are typical of large, pale individuals, which breed in southern Alaska; more northerly breeders are smaller, redder, and migrate and breed up to 2–3 weeks later, according to the later snowmelt at their eventual tundra nest sites. But it wasn’t until about 2015 that we realized that something else was going on: the 4-week window of departures was getting incrementally earlier across the years, at about half a day per year.

Individual Bar-tailed godwits are remarkably consistent in their migration timing, and 4YYRB departed New Zealand in a window of just 8 days during 2008–2020. However, his series of departures mirrored the population-wide change across this period. In 2008, he departed on 13 March, in the third of 17 sub-flocks to go that year. His next 11 departures fluctuated between 8 and 12 March (as expected with annually variable social and environmental conditions), but crept gradually earlier. His 2020 departure on 6 March (also in that year’s third departing group) was his earliest ever, punctuating an overall 13-year advancement of 0.34 days per year.

By collecting similar data for all of his individually-marked compatriots at the Manawatu (a total of 124 that graced the study for at least 3 years), we could see that 4YYRB was not an exception but the rule: the population advancement occurred through individuals changing their timing. This is an encouraging message regarding contemporary adaption in long-distance migratory birds, which are often thought to be relatively unresponsive to change, either because their tightly-scheduled itineraries have little wiggle-room, or because relevant cues don’t reach them from opposite ends of their journeys. And adult birds, in particular, are often observed to be quite set in their ways, once they figure out a routine they like. But our results show that their toolbox for adaptation to change includes year-to-year refinement to changing conditions (and perhaps learning by experience), not just evolutionary change through selection and replacement by better-adapted individuals.

But what exactly are godwits in New Zealand responding to? This is a much harder question, and not likely answerable with obsessive individual observations in one place, particularly a non-breeding site. The timing of bird migration is in fact advancing across the globe, and this is generally attributed to warmer and earlier springs making ever-earlier breeding possible and increasingly advantageous. We never tracked 4YYRB on his entire migration, but we did track a number of individual godwits from Manawatu to Alaska in 2008–2009 and 2013–2014, using light-sensitive geolocators. These small (1.5 g) and ingenious devices can roughly indicate a bird’s geographic location based on the timing of sunrise/sunset, and, because we attach them to leg-bands, they also show when a godwit is incubating a nest (which appears as unexpected ‘nights’ in the Arctic summer’s 24-hour daylight). By comparing these two temporal cohorts, we got another surprise: despite advancing their departure from New Zealand, godwits were not arriving in Alaska or breeding any earlier. According to remotely-sensed environmental data (Simeon Lisovski of the Alfred Wegener Institute handled this part, which exceeded my analytical capabilities, and much of the geolocator analysis), they should breed earlier: tundra breeding sites in Alaska were becoming snow-free and ‘greening-up’ earlier across the study period, indicating that the optimal time to raise chicks was advancing. So why weren’t they doing it?

Although we can’t prove it decisively yet, our working hypothesis is a familiar one: humans are probably screwing it up for the godwits. On their way to Alaska, godwits make one stop in the Yellow Sea to ‘refuel’ between two long flights of about 10,000 and 6,000 km. The geolocator data show that this stop, roughly one month spent on the mudflats of northeastern China and the Korean Peninsula, has been getting longer, effectively erasing the advancement in the first flight from New Zealand. During our study period, reclamation and degradation of mudflats in the Yellow Sea has significantly decreased the availability of food for shorebirds (mostly intertidal worms, shrimp and bivalves), meaning that godwits probably need more time to sufficiently fatten up for their next flight to breeding areas.

The take-home messages: In this age of unprecedented environmental perturbations, both natural and human-caused, every ecological study that continues for a decade or more, regardless of its original intent, eventually becomes a study of adaptation to global change. And only with this kind of long-term data can we measure the ability of individuals (and therefore populations) to respond to change – a capacity that can be both impressive and distressingly fragile.

Epilogue: In fact, New Zealand went into a total lockdown on 25 March 2020, after the first cases of community-spread COVID-19 were detected. Luckily, I had a house right at the edge of the mudflat, and so could continue working, without violating the lockdown, until the last godwits departed on 29 March. I eventually made it home, after the cancellation of three different return itineraries, on a ‘repatriation flight’ organized by the Dutch government. I was not able to return to New Zealand for Year 14 of my study, but I arranged for local help (thank you, David Melville) to prevent a gaping hole in the dataset. Meanwhile, godwits continued to come and go, heedless of flight restrictions. For me, maybe next year.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in