Do forest conservation initiatives effectively mitigate climate change?

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Economics

To address a wicked problem like climate change, a natural way to start is arguably to look for the path of least resistance. Declining carbon-rich tropical forests would seem to qualify in that respect. Forestlands are lost mainly due to conversion to often just modestly more profitable land uses, e.g. slash-and-burn agriculture or extensive pastures. Hence, why not pay landowners conditional incentives not to deforest, using funds from industrialised, historically high-emitting countries?

This is the compensatory economic logic behind “reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and foster conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks”, abbreviated to REDD+. The 2007 Bali COP of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) endorsed REDD+, and since multiple REDD+ projects and programmes were implemented across the tropics. Some were led by NGOs already active in conserving biodiversity. Others were commercial private initiatives selling REDD+ credits on voluntary carbon markets. Finally, public-sector subsidy programmes also featured conserving forest carbon stocks as one explicit goal, thus attracting bilateral REDD+ funding from the Global North. Consequently, these payments should also benefit the incomes and livelihoods of forest-dwelling communities.

The REDD+ cocktail would seemingly promise triple-win payoffs: forest stewards, biodiversity and the global climate would all stand to benefit. But to what extent has it worked in practise?

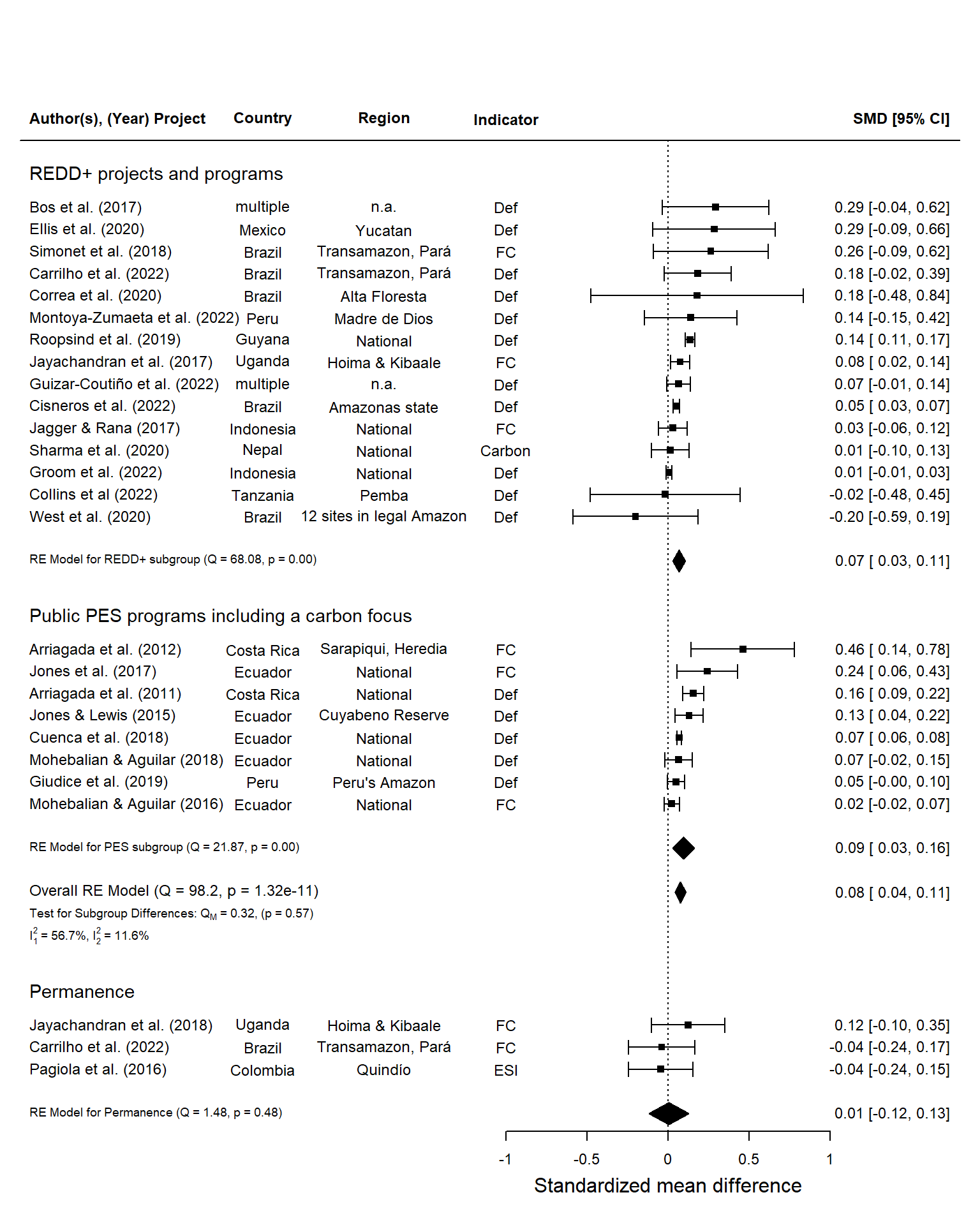

In our global meta-analysis to assess REDD+ impacts, we identified 32 quantitative studies all using rigorous statistical methods. By ‘rigorous’, we meant they would not just undertake statistically naïve before-after comparisons of the status of forests and livelihoods: they would also assess counterfactual baselines (‘what would likely have happened without the REDD+ intervention?’), e.g., as informed by observations from comparable control sites.

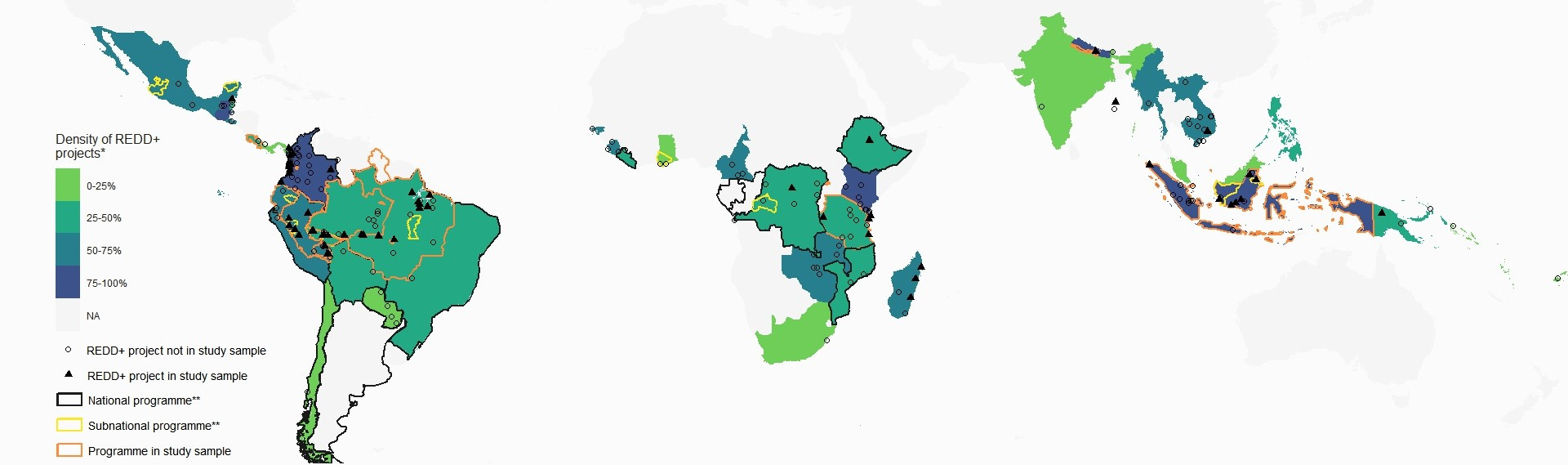

In total, we identified studies enabling us to calculate 26 forests-related and 12 socioeconomic REDD+ effect sizes. Not a lot perhaps, for a decade and a half of REDD+ action. Yet, generally quantitative impact evaluation of environmental interventions has only recently become more common. As for the REDD+ action, density (i.e., comparing to forest size) was highest in Andean countries, Indonesia and East Africa. In turn, research on REDD+ impact evaluation was biased somewhat towards Latin America.

On aggregate, we found modestly sized yet significant REDD+ impacts, for private (NGO or commercial) and public programmes fairly alike – but with otherwise large within-sample variations. Three studies tentatively indicate that deforestation tends to pick up again when REDD+ payments stop, but without eliminating forest conservation gains made while the intervention lasted.

Livelihood impacts (on incomes, consumption, assets, etc.) were even smaller (not shown here). Average positive effects were larger for incomes than for subjective wellbeing, reflecting frequent disappointment with the initial expectations REDD+ had locally raised.

But why would REDD+ impacts vary so much across our sampled studies? A moderator analysis gave us some clues.

First, projects that had been located in remote ‘high-and-far’ sites with poor market access faced also initially lower or negligible deforestation pressures, which also translated into lower REDD+ impacts: when there are less threats to fight to start with, it is also harder to make a positive difference.

Second, smart REDD+ design would also boost impacts. Spatial targeting of strategic subregions, communities or landowners, giving them preferential access to REDD+, would clearly increase forest conservation effects. In the same vein, differentiating REDD+ payments across beneficiaries (e.g., with respect to variable opportunity costs), rather than paying uniform rates, would improve socioeconomic impacts, including by better addressing equity issues.

On aggregate, our results on the one hand help delivering proof of concept for REDD+: clearly some initiatives have been able to generate sizable positive impacts, both for people and the environment. Yet on the other hand, too many REDD+ interventions have also underperformed impact-wise. Still, comparing to other types of conservation incentives, REDD+’s average environmental impact performance comes out just about as moderate.

As REDD+ currently is being upscaled to jurisdictional approaches, i.e., working more with governments than with project proponents, some conclusions are noteworthy. REDD+ interventions can achieve more conservation when they take the deforestation bull by the horns, i.e. moving away more from remote low-threatened sites to places where forests indeed are already under tangible menace. Similarly, smarter REDD+ design using spatial targeting and benefit differentiation would likely pay off for increasing impacts. Our results should thus not necessarily discourage further REDD+ actions; instead they point to concrete avenues for improving the outcomes.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in