Examining Saudi teachers’ professional competency and attitudes toward technology-integrated teaching for students with intellectual disabilities

Published in Education

When Saudi Arabia launched Vision 2030, education suddenly felt different. The national conversation shifted to digital transformation and inclusive schooling at the same time. As a special education researcher working in this context, I always wondered about a simple but uncomfortable question:

“We’ve invested in devices and platforms, but are our teachers actually ready to use them with students who have intellectual disabilities?”

This paper grew out of that question.

From policy promises to classroom realities

Saudi special education has grown rapidly, with new schools, programs, and policies defining the rights, services, and classifications for students with intellectual disabilities. Yet, in practice, very concrete obstacles keep appearing: teachers may have tablets but little meaningful training, assistive software is available but often feels too complex to use confidently, and many are understandably anxious about having to troubleshoot technical problems in the middle of a lesson.

At the same time, the research I could find from Saudi Arabia was mostly small-scale and local important but limited to single districts or institutions.

What was missing was a national, multi-region snapshot of special education teachers’ readiness to integrate technology specifically for students with intellectual disabilities, one of the most marginalized learner groups.

Building a study that captured “readiness”

I knew from international literature that “readiness” is more than just knowing how to click or swipe. It lives at the intersection of:

- Pedagogical–technological competence (TPACK)

- Attitudes and intentions (Theory of Planned Behavior)

- Confidence (self-efficacy)

- Context and adoption climate (Diffusion of Innovations)

So instead of simply asking, “Do you use technology in your class?”, I designed a questionnaire that tried to honor all of these dimensions:

- items on integrating tools into actual lessons rather than just operating devices

- items on attitudes, perceived expectations, and ease or difficulty

- items on confidence in troubleshooting and adapting tools

- items on access to trials, peer examples, and institutional support

Developing and validating this instrument piloting it, refining wording, and running factor analyses was one of the most time-consuming parts of the project, but also one of the most satisfying. It forced me to be explicit about what we really mean when we say “competent with technology.”

Reaching teachers across a vast country

Saudi Arabia is geographically huge, and special education teachers are scattered across regions and school types. Using an online survey and cluster sampling, I ultimately gathered responses from 443 teachers working directly with students with intellectual disabilities.

Seeing the dataset for the first time was a genuine “high” in this project: it felt like the beginning of a truly national conversation, not just a local snapshot.

The findings that surprised me

Some results fit what I expected; others were sobering.

- Competency: On average, teachers rated their professional competency in technology-integrated teaching as moderate (mean 3.83 out of 5). They felt relatively confident about using and adapting tools, but less confident in troubleshooting technical problems, which emerged as a clear weak spot. (Table 1, page 9)

- Attitudes: Teachers’ attitudes were very positive (mean 4.21 out of 5). They strongly agreed that technology can improve learning outcomes and that they are open to new tools. (Table 2, page 11)

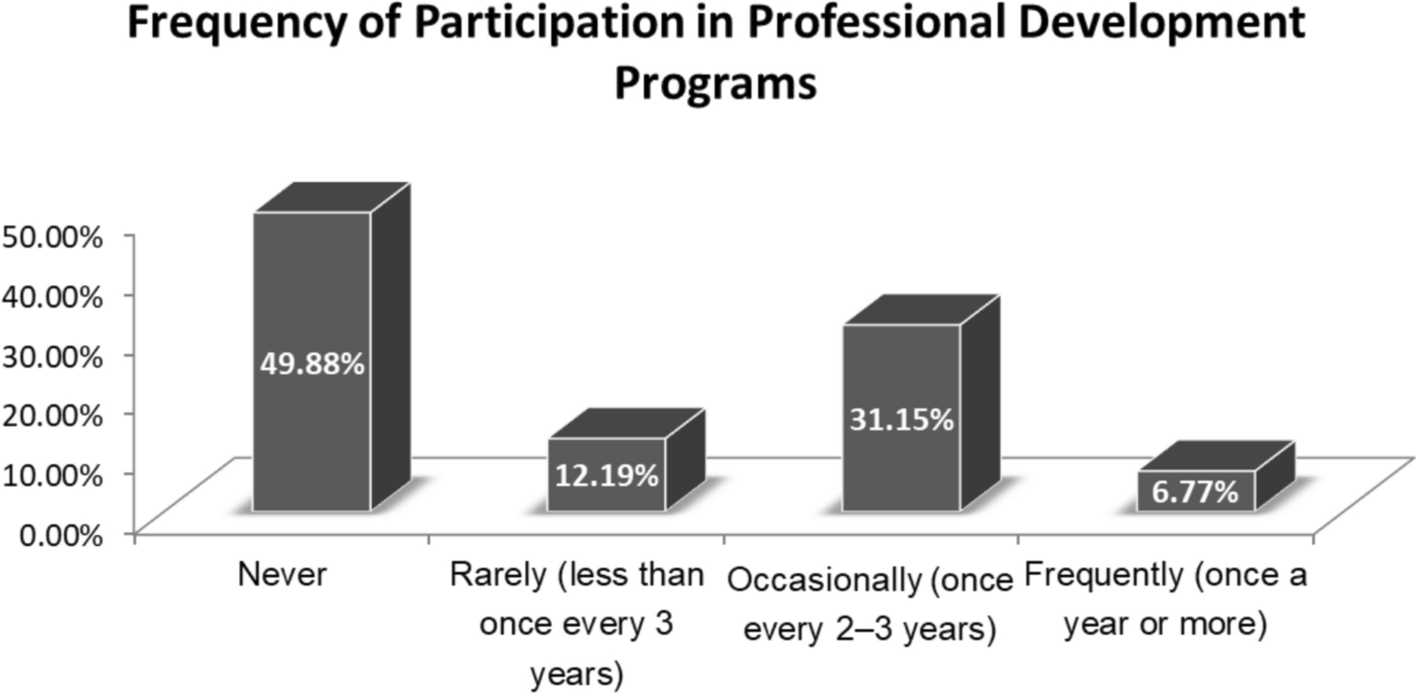

- Professional development: This was the most striking and worrying finding. Nearly half of the teachers (49.88%) had never participated in any professional development focused on technology integration for students with intellectual disabilities. The bar chart on page 10 makes this gap painfully clear.

Yet, among those who did attend PD, most rated it as effective or very effective (Figure 2, page 11), suggesting that when teachers are given good training, they feel the difference.

- Who feels most ready? Younger teachers and those in the 11–15-year experience range showed higher competency scores, while gender differences were negligible.

In short: teachers want to use technology, largely believe in it, and feel moderately capable but the system has not consistently invested in giving them sustained, targeted support.

The low points: limitations and self-critique

A Behind the Paper piece should also acknowledge the doubts.

For me, two issues were particularly challenging:

- Self-report data. I knew from the start that asking teachers to rate their own competence has limitations. Social desirability, differing internal standards, and lack of observational data all matter. The paper is very explicit about these limitations and calls for future studies to include classroom observations and performance measures.

- Cross-sectional design. The theoretical framework suggests pathways how professional development might shape self-efficacy, which then shapes competence and intention. But with cross-sectional data, we have to be careful not to over-claim causality. Some of the most interesting relationships in the data are, for now, hypothesis-generating, not definitive proof.

Being honest about these limitations in the discussion was not easy, but it was necessary. Good theory deserves cautious interpretation, not over-confident storytelling.

What this study changed for me

Working through the data, I found my own thinking shifting in three ways:

- I stopped assuming that “more technology” automatically means “better outcomes.” The real bottleneck is professional learning, not just devices.

- I began to see age and experience patterns not as simple “digital native vs. non-native” stories, but as clues about where mentoring and peer coaching could be most powerful.

- I became more convinced that special education needs its own evidence base on technology integration, not just borrowed insights from general education.

What’s next?

This study is a descriptive starting point. The next steps I hope to see some of which I plan to pursue include:

- designing practice-based PD models that combine workshops, peer coaching, and follow-up support

- testing these models in longitudinal designs to see whether teacher competence and classroom practice truly change over time

- examining which specific tools (from low-tech aids to advanced apps) are most useful for students with different profiles of intellectual disability

Ultimately, the goal is simple: when a student with intellectual disabilities walks into a classroom in any region of Saudi Arabia, the technology around them should not be decorative it should be used confidently, thoughtfully, and routinely to support their learning.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Education

An international, peer-reviewed open access journal that publishes original work in all areas of education, serving the community as a broad-scope journal for academic trends and future developments in the field.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Empowering Education through AI: Opportunities, Challenges and Risk Governance

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is reshaping the landscape of education as a double-edged sword. On one hand, it holds great promise for empowering teaching, learning, assessment, and educational management by making them more efficient, accurate, adaptive, and responsive. On the other hand, the increasing integration of AI in education elicits significant pedagogical, ethical, social, and policy concerns, such as reduced learner agency, algorithmic control, academic misconduct, and exacerbated educational disparities. Without proper risk governance, the AI technologies intended to empower education may end up disrupting the educational processes and wreaking chaos on educational development. This calls for coordinated efforts from policymakers, researchers, and practitioners worldwide to ensure the legitimate, appropriate, responsible, and ethical use of AI in education.

Against this backdrop, this Collection aims to promote critical inquiry into the intricate and multifaceted features of AI use in education. We particularly welcome interdisciplinary perspectives that explicate how policymakers, researchers, educators, and learners can participate in and collaborate to leverage the transformative power of AI while mitigating the potential risks within different educational scenarios and across diversified cultural contexts. Potential topics include (but are not limited to):

1. Social, ethical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioural terrains of AI use in education

2. Human-AI collaboration in teaching, learning, assessment, and educational management

3. Learner agency, self-regulation, and AI-empowered learning

4. Teacher professional development in AI-empowered education

5. AI literacy for educators and learners

6. Educational equity and academic integrity in the AI era

7. Policy innovation and risk governance for AI use in various educational settings

8. Cross-cultural perspectives on AI use and governance in education

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 4

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence (AI); Human-AI collaboration; AI-empowered education; policy innovation; risk governance; educational equity; academic integrity

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 26, 2026

Empowering Education: Interdisciplinary Convergence and Skill Ecosystem Reconstruction for a Sustainable Future

In an era of unprecedented environmental and societal challenges, education systems must transform to empower students as catalysts for sustainable futures. This Collection advances sustainability education beyond environmental awareness, focusing on developing critical competencies—systems thinking, ethical decision-making, and innovative problem-solving—essential for building resilient societies.

We call for systemic reimagining of education across all levels and disciplines, particularly highlighting:

• Cross-curricular integration of sustainability principles in STEM and vocational training

• Pedagogical innovations that bridge theory-practice gaps

• Industry-education synergies for green skills development

• Digital transformation of sustainability learning

Key Research Domains

Contributions should address critical intersections of sustainability and education, including but not limited to:

• Curriculum innovation for actionable sustainability knowledge

• Evidence-based pedagogical strategies fostering sustainability literacy

• Vocational education redesign for green economy readiness

• Industry partnerships enhancing real-world learning

• Digital technologies (AI, data analytics) in sustainability education

• Assessment frameworks for sustainability competencies

• Teacher professional development models

• Global citizenship and ethical responsibility cultivation

Transformative Objectives

By examining how curricula, teaching strategies, and learning environments can embed sustainability principles, this Special Issue aims to:

• Equip learners with values-driven leadership capabilities

• Develop scalable solutions for environmental, social, and economic challenges

• Catalyze education’s role in achieving global sustainability goals

We invite submissions offering actionable insights and transformative frameworks to prepare students for thriving in a rapidly evolving world.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in