Reconciling biodiversity and human well-being in a mega-diverse and crowded country

Published in Earth & Environment

By: Jagdish Krishnaswamy, Stotra Chakrabarti, Uma Ramakrishnan, & Arjun Srivathsa

Prologue:

Despite having over 1.4 billion people, many of whom are economically impoverished and directly rely on immediate natural resources, India retains viable populations of several megafauna, unique and spectacular habitats, and endemic species. India’s remarkably successful record of conserving its biodiversity has sometimes posed a heavy burden on local communities who share space with wildlife. Developmental aspirations of a growing economy and climate change pose new challenges for the future of India’s rich biodiversity. While preserving India’s biodiversity is globally important for its intrinsic value, it is also critical to millions of Indians who depend on it for sustenance and livelihoods. We propose an evidence-based and implementable pathway by which India can address this immense challenge through landscape scale conservation.

The idea of modern ‘inviolate’ Protected Areas was mainstreamed in the late 19th century to conserve areas of critical importance to life and culture. Human engagement to safeguard nature and natural resources, however, is ancient. Earliest known records of terrestrial and aquatic regions being spared from human-use, either completely or partially by royal decree, date back to 300 BC from south Asia. Protected Areas have long served as sanctuaries for natural spaces where biodiversity has lingered and revived in the face of the Anthropocene. From the former hunting reserves of elites to the current fenced parks that keep out local communities, nature’s safe spaces face a key challenge –– that of scale. Protected Areas cover only a fraction of the land and seascapes, while majority of important habitats are shared between humans and wild animals. Currently only about 15% of terrestrial habitats and ~7% of our oceans are under some form of legal protection1. While conventional conservation paradigms and practices revolve around such land-sparing, spaces to spare are both limited and fast shrinking. Reimagining conservation by integrating ‘land-sharing’ wherein spaces shared between humans and biodiversity can be included and safeguarded, is thus critical to pragmatically maintain ecological and human well-being into the future.

Our Study:

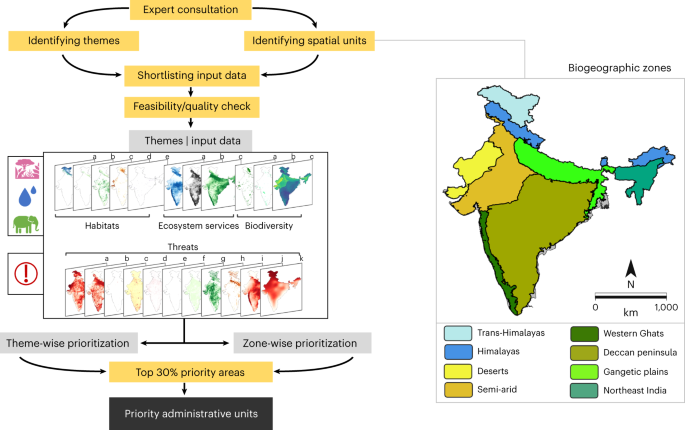

Managing the dual needs of biodiversity conservation and human aspirations requires delineating areas that can insure species and critical habitats against habitat alteration and climate change, while facilitating the provisioning of multiple ecosystem services. We investigated whether it was possible to prioritize such multi-use landscapes in India.

We adopted a spatial prioritization approach to identify sites within each biome in the country that (i) represent key and rare natural habitats, (ii) provide crucial ecosystem services such as carbon and water, and (iii) contain diversity of threatened species. These three themes showed moderate spatial overlaps, to the extent that nearly 40% of the sites that represented areas which provide crucial ecosystem services were not covered either by the habitat or species-diversity priority areas. Such scale mismatches depict the pitfalls of using a single criterion to assign importance value to any area. Significantly, only 15% of the top 30% priority sites that included all the three (aforementioned) conservation themes were encompassed within the current Protected Area network, while the majority were human-dominated landscapes. Such a delineation further emphasizes the need for landscape-level conservation approaches that are inclusive of spaces shared between humans and wildlife. Surprisingly, locations constituting the top 30% priority sites as per our assessment were largely connected, thereby highlighting the need for landscape scale conservation that incorporates connectivity planning.

Instances of space sharing between humans and wildlife in India. A. an Asian lioness and her cub at a village temple outside Gir forests in Gujarat, B. a Gangetic River dolphin surfacing near fishing boats at the Kosi-Ganga confluence, Bihar, C. a male Great Indian Bustard displaying for a mate near a wind turbine – their habitats are heavily crisscrossed with powerlines and renewable energy resources, D. gharials and Indian skimmers at the bank of the Chambal River in Rajasthan, E. a male fan-throated lizard displaying it’s brilliant throat in a human dominated area, and F. Indian rhinos sharing space with domestic livestock in Pobitora, Assam. These images paint a cohabitation canvas and presses the urgency of landscape level conservation strategies instead of just relying on conventional inviolate protected areas to safeguard biodiversity and human health in India. Photo credits: Stotra Chakrabarti | Jagdish Krishnaswamy | Tarun Nair | Vishal Varma | Prasenjeet Yadav | Harshini Jhala

Besides developing these thematic classifications, we also identified areas where biodiversity, ecosystem services, and key habitats are threatened by human actions and climate alterations. This ‘threat layer’ represented areas that have or soon will surpass thresholds beyond which interventions for sustainable land-use practices are not realistic. By incorporating threats, we were able to achieve a trade-off between sites prioritized for their conservation potential with the feasibility of safeguarding them in the wake of on-going or future negative impacts. We then presented the consolidated spatial analysis across administrative units (districts) so as to directly benefit land-use policymaking. This allowed us to demarcate land parcels and districts that harbor significant biodiversity and ecosystem potential (priority districts), and therefore are in dire need of effective protection. While such a spatial analysis allows for a strategic roadmap to secure biodiversity and ecosystem services, it is essential to not dampen the economic aspirations of the society, especially when India has one of the fastest growing economies in Asia. Protective measures that (only) rely on creating inviolate areas for conservation can challenge economic growth and cause severe conflicts.

To reconcile land-use planning ensuing from our spatial prioritization analysis with the potential for economic growth, we mapped the spatial congruence of priority districts with areas allocated for economic development under the Government of India’s Aspirational Districts Program. This program was launched in 2018 to bolster sustainable growth across >100 economically impoverished districts across the country2. We recommend that sites where the aspirational districts overlap with high priority districts, biodiversity value and ecosystem services should be safeguarded through regulatory and participatory approaches involving management zoning, landscape level planning, and community driven conservation.

Top 10%, 20% and 30% conservation priority areas in India based on the key habitats they cover, species diversity they harbor, and the ecosystem services they provide. Current Protected Areas are overlaid to show the extent of overlap and spatial congruence with high priority locations.

Conclusion

Since its independence in 1947, contrary to many a dire prediction regarding the imminent extinction of its major wildlife assemblage, India has championed the recovery of multiple species that were once severely threatened. Such recovery was significantly aided by strong legislation initiated in the 1970s, and the participation of civil society, coupled with the socio-cultural ethos and acceptance of local communities that has promoted coexistence. While Protected Areas became strongholds for recovering biodiversity in India, they currently cover <5% of the country’s land area. Conversely, the recently concluded COP15 pledged to achieve a goal of protecting 30% of the world’s land and seascapes under some form of conservation by 20301.

If India were to accomplish this global goal, we see no alternative to a landscape-level conservation approach that embraces a judicious mix of land-sharing and land-sparing strategies. Results from our spatial prioritization exercise should offer prescriptive goals to policy makers and managers for sustainable development that safeguards habitats, biodiversity, and ecosystem services without compromising the economical aspirations of the people.

How India progresses on its ambitious development and ecological restoration goals simultaneously will be watched keenly by many other countries. While academic scholarship and global agreements are abundant, actions are often compromised because evidence-based arguments lack concrete, tangible targets for policy makers. We hope that our study, through the alignment of administrative districts and governmental development agendas provides implementable opportunities to conserve biodiversity for human wellbeing, and meet the global goals and targets, safeguarding our collective future on earth.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Sustainability

This journal publishes significant original research from a broad range of natural, social and engineering fields about sustainability, its policy dimensions and possible solutions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in