The delayed rise of flowering plants

Published in Ecology & Evolution

This project started back in 2016. Back then, my two co-authors (Susana Magallón and Hervé Sauquet) and I simply wanted to build and date a phylogenetic tree with all angiosperm families in it and see how the timing of families' origins looked like. This objective was grounded, for the most part, in what Charles Darwin called an ‘abominable mystery’: flowering plants suddenly appeared in the Early Cretaceous and almost immediately (by geological standards) started to diversify dramatically and nowadays they are the dominant and most important group of terrestrial plants.

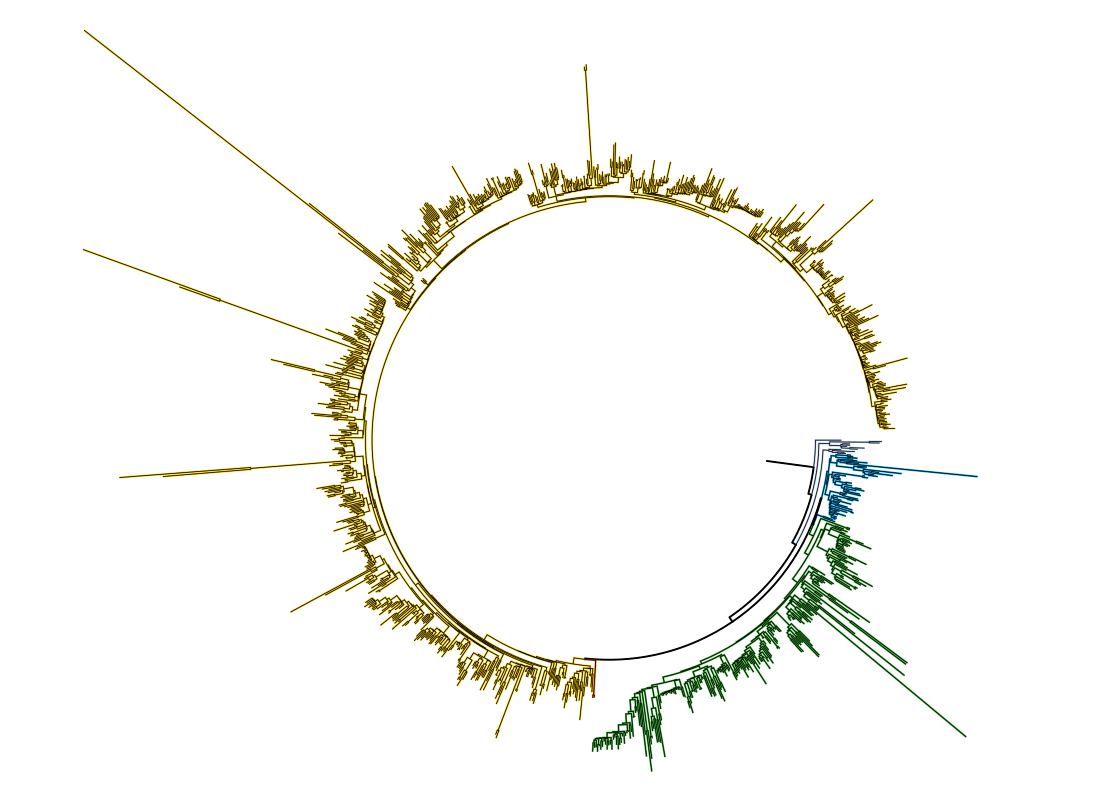

But the project is as old as my kid, so naturally many things surrounding the project changed along the way. The project's original goals eventually morphed and the project grew into a more ambitious one. Eventually, we aimed to document the age of origin of all 435 angiosperm families and explore when did they first started to diversify into their living representatives (that is, we wanted to also estimate families' crown ages). We painstakingly revised family-level phylogenies to identify those species that would represent the ‘crown’ node of every family and assembled the corresponding molecular dataset. Before even reaching the fortieth family it felt like we had crossed the Rubicon, so we were not looking back. Surprisingly, six months later we produced our first phylogeny!

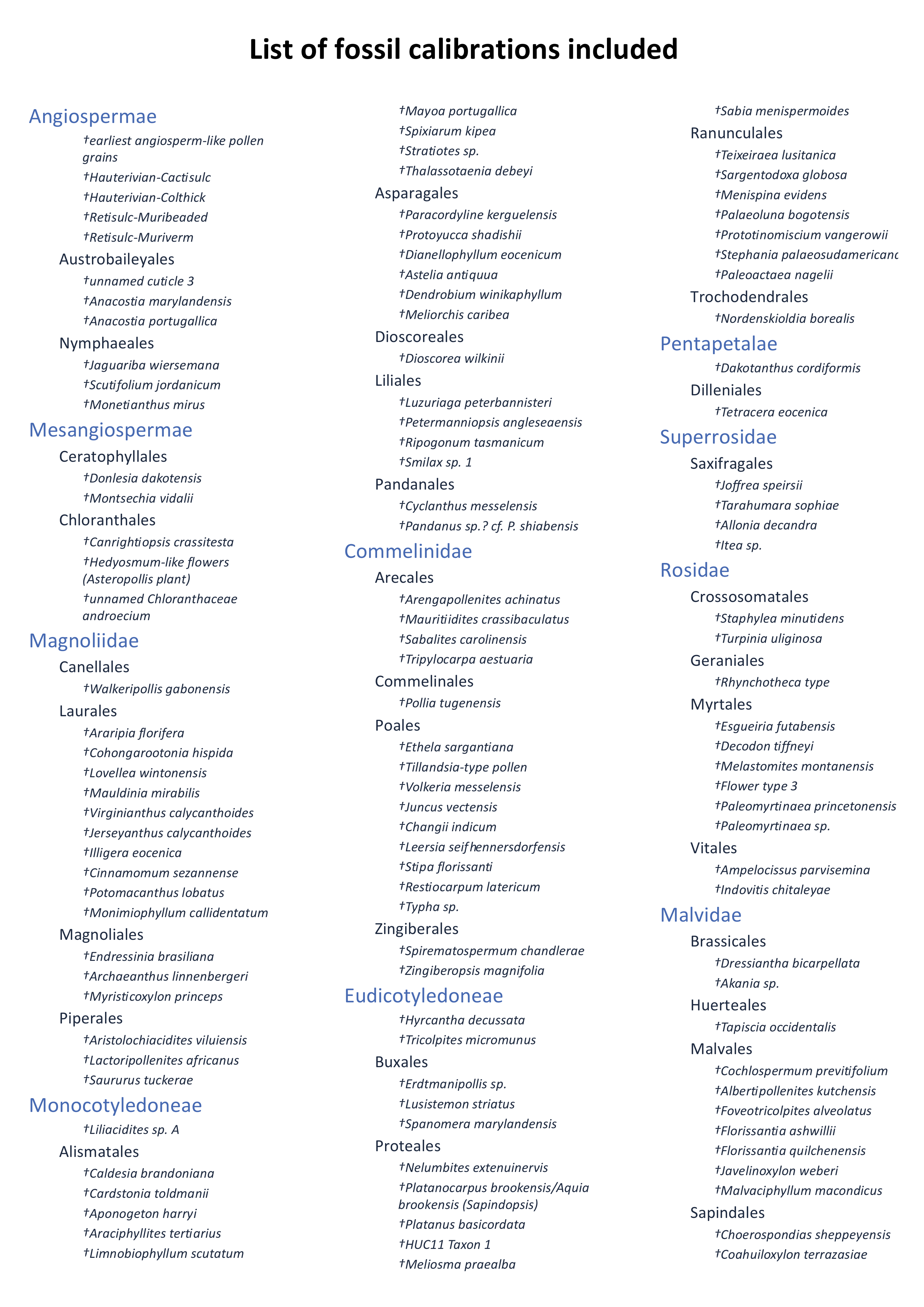

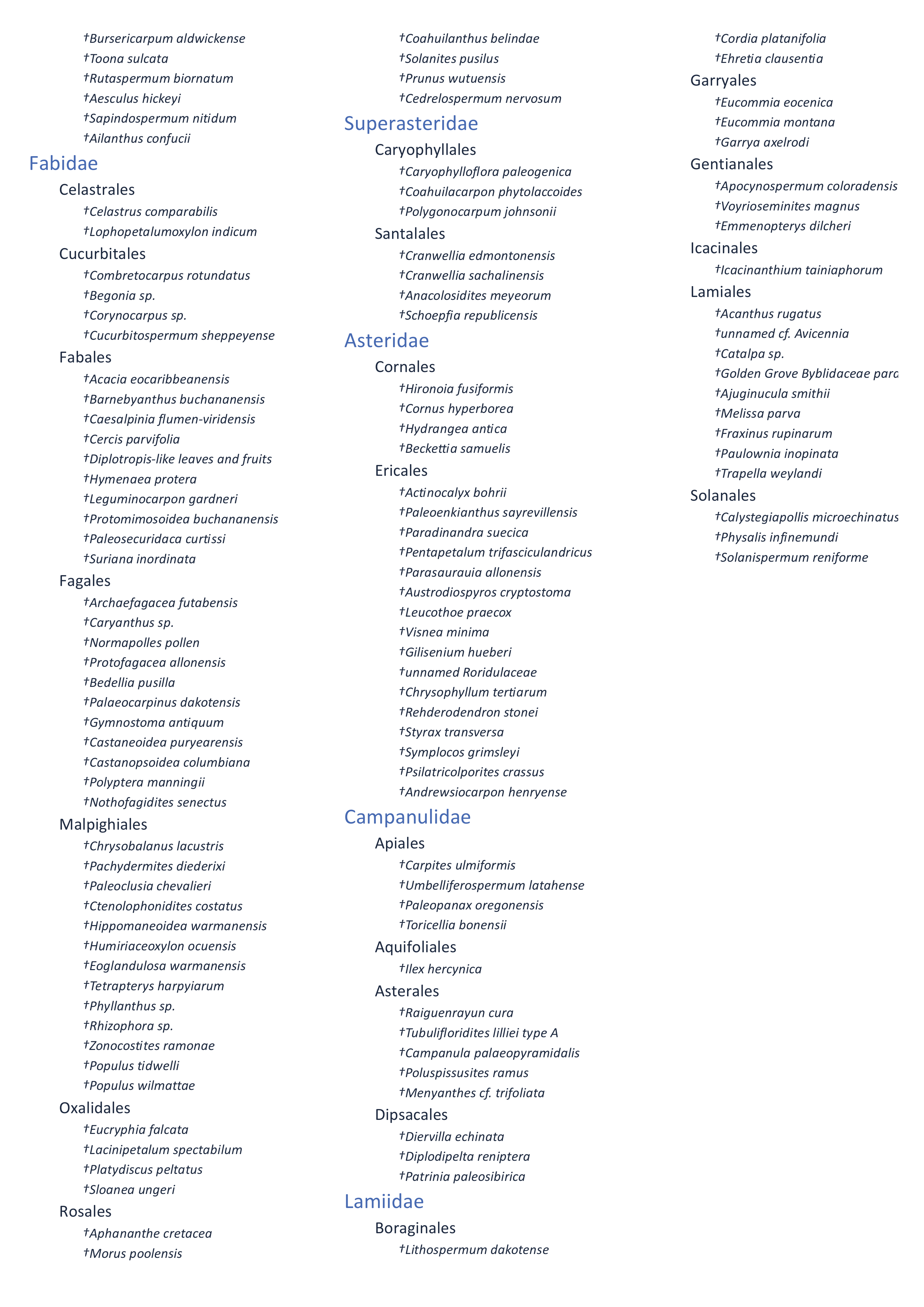

The next step were fossils. Looking at the fossilized remains of a plant that grew so long ago is mind blowing (sometimes I think I should have been a paleobotanist!). We wanted to do a good job at documenting fossils and do justice to the fossil record of angiosperms, because fossil calibration is the single most critical step in any divergence time analysis. At the end, we assembled and documented the largest high-quality fossil dataset for angiosperms (238 fossils), making every fossil in our list traceable and open to scrutiny by providing a 384-page-long document!

Long story short, it took about two and a half years to settle on the final fossil calibration list and then perform the dating analyses, and almost six more months to get our final results and agree on their interpretation. In sum, our results show that the rise of modern flowering plants (that is, families’ crown ages) was delayed for 37–56 million years after the origin of families (that is, families' stem ages). Getting to this point involved four different computers, two servers, one nerve-racking data recovery from a dead computer, many crashed analyses, in-person meetings in Mexico, China and the US, plenty more Zoom meetings, and more than enough toddler flus.

By the time the dating results were in, we had gathered good-quality geographic distribution data for 250k angiosperms. So we decided to go a step further (why not?) and test the idea that older families are disproportionately represented in tropical regions (although this idea is not novel). The results were unsurprising, but they led to the discovery that the rise of modern angiosperms was delayed for longer in tropical ecosystems than in temperate and arid ecosystems. Perhaps most exciting, is that this delay provides a good example of the decoupling of taxonomic diversification and ecological dominance! But why this delay? We have some hypotheses about extinction, ecological opportunity and morphological evolution, but in reality we are not entirely sure.

Four years later and we have many more questions.

Science is like Ravel's Boléro.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Ecology & Evolution

This journal is interested in the full spectrum of ecological and evolutionary biology, encompassing approaches at the molecular, organismal, population, community and ecosystem levels, as well as relevant parts of the social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning of global peatlands

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jul 27, 2026

Understanding species redistributions under global climate change

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Jun 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Excellent work!!

The reason for "the rise of modern angiosperms was delayed for longer in tropical ecosystems than in temperate and arid ecosystems", is there a possibility that the evolved flowering plants in the high latitude areas and then migrated to the tropics?

By the way, the flowering image is wonderful, is this your work? Do you have the names (Latin name, source, credit) of these 54 flowers? Probably you can email me a word version of the figure caption (gaojg@pku.edu.cn).

Thank for your comment.

Keep in mind that if you look at stem ages, tropical biomes harbor older families (on average) than temperate and arid biomes. However, what is interesting is that when you look at the fuse times (stem age minus crown age) you get that the tropics harbor families with longer fuses than temperate and arid biomes. This means that families in the tropics originated earlier (on average), but took longer to start diversifying into their living species.